John B. Anderson, who made quixotic run for president the year Reagan won the White House, dies at 95

John B. Anderson, a former Illinois congressman whose eloquent and quixotic 1980 presidential campaign as an independent became a national sideshow as voters carried Ronald Reagan to the White House, has died at his home in Washington. He was 95.

For the record:

10:40 a.m. Dec. 5, 2017An earlier version of this story incorrectly said that Anderson’s 7% of the vote helped Ronald Reagan defeat President Carter. Reagan won 50.7% of the vote to President Carter’s 41%. Anderson’s 7% was not the deciding factor.

His death Sunday was confirmed by his daughter, Diane Anderson.

A 10-term congressman, Anderson waged an independent campaign in 1980 against President Carter and his Republican challenger Reagan. Anderson received 7% of the vote, many of those votes coming at Carter’s expense.

In his later years, Anderson became a lecturer and spokesman for political reform, drawing attention every four years as he was called on to discuss other third-party presidential candidates.

Anderson was a Republican for nearly all of his elected political career, but his views became more liberal as his party shifted rightward. He left the party altogether when, as a GOP presidential candidate in 1980, he lost several primaries and decided to go it alone as an independent.

Carter refused to debate Anderson, but Reagan, who had been California’s governor, agreed to a televised confrontation, making Anderson the first third-party presidential candidate to debate a major-party opponent on TV.

In November 1980, Anderson’s National Unity Party platform drew nearly 7% of the nationwide popular vote, sapping more support from Carter than from Reagan.

Born Feb. 15, 1922, in Rockford, Ill., John Bayard Anderson was the son of Swedish immigrants who ran a grocery store. The family belonged to the Evangelical Free Church, a small, conservative Swedish American sect, and Anderson’s faith deepened after he was “born again” at age 9 during a summer tent meeting. As a boy, he and his siblings would play church. Blond-haired John was always the minister.

“He could really preach a sermon,” his sister, Helen, once recalled. “We would sit there with our mouths open.”

A star debater in high school, where he was class valedictorian, and in college, where he was a Phi Beta Kappa graduate, Anderson earned a bachelor’s degree in political science from the University of Illinois in 1942 and a law degree in 1946. In World War II, he was awarded four battle stars in the Army field artillery in Europe. After the war, he received a second law degree from Harvard University.

Anderson practiced law in Rockford until 1952, when he joined the United States foreign service. While getting his picture taken for his passport, Anderson met Keke Machakos, the State Department photographer. The first picture did not turn out, so she called him in for a second. They began dating and married the following year.

Anderson’s political career began with a successful 1956 campaign for state’s attorney — the local prosecutor — in Winnebago County, Ill. In 1960, as a Republican, he was elected to an open congressional seat representing Illinois’ 16th District, a GOP heartland in northwest Illinois.

Anderson arrived in Washington at the start of the Kennedy administration, pledging to oppose such liberal Democratic notions as Medicare and federal aid for education. GOP leaders trotted out their persuasive colleague for party “truth squads” to rebut the programs of the Kennedy administration.

Three times in his early terms, Anderson sponsored a constitutional amendment that would have officially declared the United States to be a Christian nation. Criticized later during his presidential campaign, which counted on Jewish voters’ support, Anderson apologized to Jewish leaders and explained that he had introduced the proposal for a clergyman but never lobbied for it.

By the late ’60s, Anderson was less recognizable as a conservative Republican. He remained mostly in line with his party on economic matters but broke with the GOP by voting for a bill that outlawed racial discrimination in housing, supporting the Equal Rights Amendment, criticizing wasteful defense spending and backing restrictions on guns and nuclear weapons. He spoke out against the Vietnam War and was among the first Republicans to call for President Nixon’s resignation during the Watergate scandal.

Colleagues described him as brilliant, principled and hard working, but also arrogant, overly serious and sanctimonious.

In 1979, at age 57, Anderson began campaigning for president as a moderate Republican. He called for restoring the “vital center that can bind our nation and society together.”

The Times described Anderson during the campaign as “the sole bearer [in the race] of the frayed banner of GOP liberalism.” For instance, he was alone among the Republican candidates in supporting federally funded abortions for poor women.

From the beginning, the little-known congressman conceded that his was a long-shot campaign. Anderson’s hope in the primary race for the GOP nomination was that his conservative opponents would divide the party’s right, making his share of the left-center look large. The GOP presidential field at that point included Reagan, Texas Gov. John B. Connally, future Reagan running mate George H.W. Bush, Kansas Sen. Bob Dole and Tennessee Sen. Howard Baker.

Anderson became a favorite among liberal voters who were disenchanted with Carter yet also dissatisfied with other Democrats. Actor Paul Newman offered to make commercials for Anderson, and television producer Norman Lear took out newspaper ads touting his candidacy. Anderson became a darling of columnists, who praised his intelligence, eloquence and integrity.

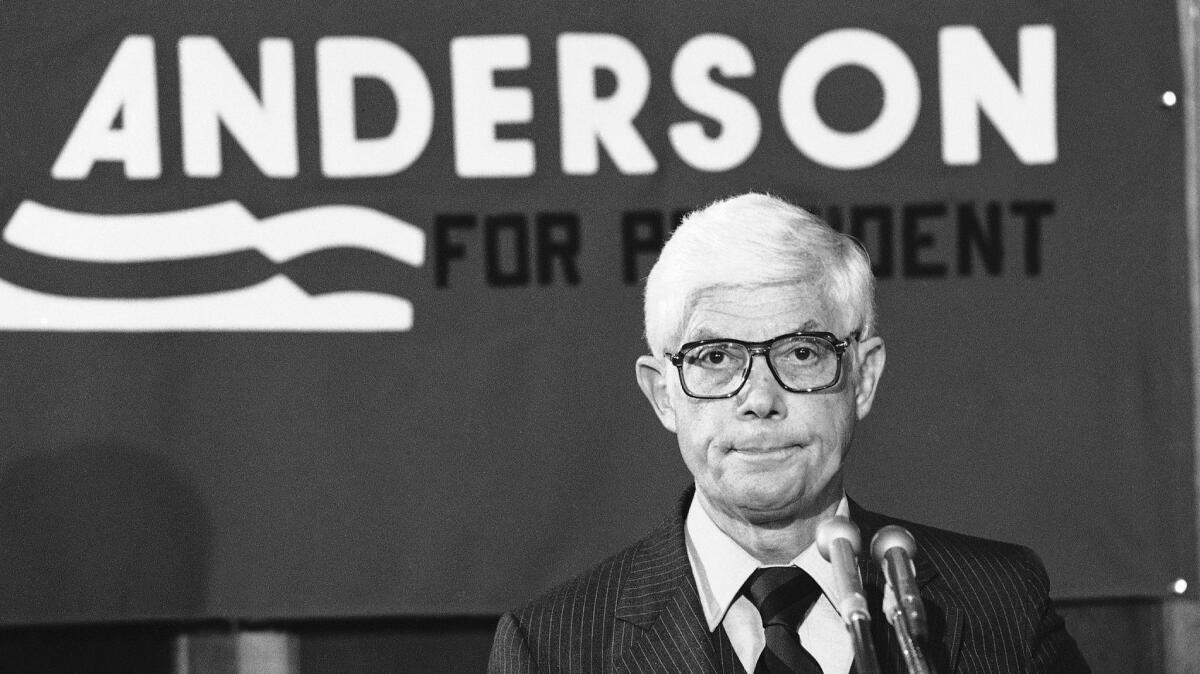

On the stump, Anderson deftly employed his public speaking skills. While Bush was quoting malaprop baseball legend Yogi Berra, Anderson cited Tennyson, Thoreau and Teddy Roosevelt. Some voters, particularly college students, warmed to his delivery, but his “$50 vocabulary” turned off others. The Washington Post described the man in boxy glasses and a helmet of snowy hair as more a “traveling scholar” than a candidate.

“Seldom does he use a five-word sentence when 30 words will do just as well,” the political writer observed.

Anderson also was criticized for his “50-50 plan.” With America’s oil crisis of the 1970s ongoing, Anderson proposed a 50-cent-per-gallon gasoline tax to discourage consumption. The gas tax would be more than offset by his proposed 50% cut in Social Security taxes, he argued. But audiences tended to hear the plan’s first part—the tax—and shut him out before he could pitch the second.

Still, Anderson’s rag-tag campaign had a charm about it. “Doonesbury” cartoonist Garry Trudeau devoted a series of strips to the confusion of the Anderson bandwagon. In one, Anderson explained that his advance man was whoever exited the car before he did.

After losing primaries in six states — but winning nearly 60 delegates — Anderson withdrew from the Republican field to continue his candidacy as an independent. For Anderson’s campaign to remain viable, however, he had to get on the ballot in all 50 states, and Democrats were challenging his inclusion in court because they worried he would steal votes from Carter.

Carter’s campaign dismissed Anderson as appealing only to the “wine and cheese set” of educated Northeastern liberals.

“He didn’t have any real hope of winning,’’ said David Gillespie, an expert on third-party candidates . “I think what he wanted to do was provide an alternative to more progressive Republicans, as the party of Lincoln became the party of Reagan that particular year, and also to provide an alternative to Democrats.”

Even the debate with Reagan didn’t help.

“We didn’t get the bounce that I had hoped for,” Anderson told journalist Jim Lehrer in 1999.

By the time Reagan and Carter debated five weeks later, Anderson had dropped in the polls and was not invited, a slight he called “absolutely crushing.”

Although Anderson insisted throughout his campaign that he would draw support evenly from Reagan and Carter, the fears of the Democratic camp came true: Anderson’s National Unity Party finished with just under 7% of the popular vote — 5.7 million votes — compared with Reagan’s 51% and Carter’s 41%. Anderson won no electoral votes, but his performance earned him federal subsidies to pay off his campaign’s debt. Anderson never sought another elected office, though he agreed to be on California’s presidential primary ballot in 2000 at the urging of a group of young supporters.

After leaving politics, he practiced law and held various visiting professorships. He also wrote books and editorials about the American economy, the need for televised presidential debates and political reform.

Anderson is survived by his wife; son John Jr.; daughters Eleanora, Diane, Karen and Susan; and 11 grandchildren.

Ritsch is a former Times staff writer

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.