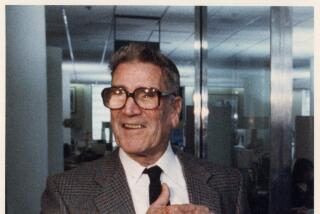

One-time Nixon aide Jeb Stuart Magruder, convicted in Watergate, dies

Jeb Stuart Magruder, the former White House aide who served seven months in prison for his role in the Watergate scandal that forced Richard Nixon to resign from the presidency in 1974, has died. He was 79.

Magruder, a retired Presbyterian minister, died Sunday in Danbury, Conn., of complications from a stroke. Jeffrey H. Hull of the Hull Funeral Home in Danbury confirmed his death.

Magruder — the politically active head of two small Los Angeles cosmetics companies and the Southern California coordinator for the 1968 Nixon campaign — was appointed as a special assistant to the president in 1969 to manage White House public relations operations.

In 1971, Magruder left his White House job to help organize the Committee to Re-elect the President (CRP), whose head became former Atty. Gen. John Mitchell.

Magruder was deputy director for the reelection campaign committee. He later directed the Inaugural Committee staff for Nixon’s 1973 Inaugural celebration and became director of policy planning at the Commerce Department — a job he abruptly quit in April 1973 in the wake of disclosures to Senate investigators that he and White House counsel John W. Dean III had prior knowledge of the bugging of Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington in 1972.

Granted limited immunity for his cooperation with prosecutors, Magruder testified before the Senate Watergate committee in June 1973 that Mitchell personally approved CRP general counsel G. Gordon Liddy’s political intelligence-gathering plans that included bugging at the Watergate, and that Mitchell took part in the ensuing cover-up.

“As far as I know, at no point during this entire period from the planning of the Watergate to the time of trying to keep it from the public view did the president have any knowledge of our errors in this matter,” Magruder said in his opening statement.

Nixon, he said, “had confidence in his aides, and I must confess that some of them failed him. I regret that I must today name others who participated with me in the Watergate affair.”

In August 1973, Magruder pleaded guilty to one count of conspiracy to wiretap, obstruct justice and defraud the United States. In return for the limited charge, he had agreed to testify for the government at the future trials of other alleged conspirators.

The next year — in May 1974 — Magruder was sentenced to 10 months to four years in a federal minimum security prison camp. Before his sentencing, he assured Judge John J. Sirica that “I know what I have done.”

Saying that he had lost his “ethical compass” and found it “almost impossible” to face the confusion in the eyes of his four children and the heartbreak in the eyes of his wife, Gail, Magruder said he was “confident this country will survive its Watergate and its Jeb Magruders.”

In 2003, the former Watergate conspirator was back in the news when he came forward in the PBS documentary “Watergate Plus 30: Shadow of History” — and in an Associated Press story just prior to the airing of the documentary — with the revelation that Nixon had personally ordered the Watergate break-in.

Magruder said he was meeting with Mitchell in Key Biscayne, Fla., on March 30, 1972, when he heard Nixon tell Mitchell over the phone to proceed with the plan to break into Democratic National Committee headquarters and bug the telephone of party Chairman Lawrence O’Brien.

Explaining his long silence over Nixon’s alleged personal authorization of the break-in, Magruder told the AP: “Nobody ever asked me a question about that.”

Asked in an interview on NBC’s “Today” show why he was finally telling the story, Magruder added that when he testified, he had no idea that former White House counsel Dean “was going to testify, in a sense, do the president in. And I was still a loyal Nixon supporter. And we thought — I think we all thought — that we would get pardons after the fact.”

Dean told the AP in 2003 that he was surprised when Magruder had recently told him that Nixon authorized the break-in.

“I have no reason to doubt that it happened as he describes it, but I have never seen a scintilla of evidence that Nixon knew about the plans for the Watergate break-in or that the likes of Gordon Liddy were operating at the reelection committee,” said Dean.

Historian Stanley Kutler, an expert on Nixon’s White House tapes, called Magruder’s allegation “the dubious word of a dubious character.”

If there had been such a phone conversation between Nixon and Mitchell, Kutler told the AP, there would be a White House recording of it.

After his release from prison in Pennsylvania in 1975 after seven months, Magruder worked for Young Life, a ministry to high school students. In 1978, he entered Princeton Theological Seminary.

“The church was a place where I could have a redemptive experience,” he told the AP in 2003. “When you go through what I went through — and it was such a negative experience — I wanted to go back to something.”

After earning his master of divinity degree and being ordained as a Presbyterian minister in 1981, Magruder served as associate pastor at First Presbyterian Church in Burlingame, Calif. In 1984, he became executive minster of First Community Church in Columbus, Ohio, where he served until he became pastor of First Presbyterian Church in Lexington, Ky., in 1990.

He left First Presbyterian Church in 1998 and spent the next several years working as a church fund-raising consultant.

In 1988, Magruder was heading a commission on ethics and values in Columbus.

“I’m aware that there might be some irony associated with that,” he told the New York Times. “But this is a natural issue for me. I had one of the great ethical dilemmas of all time.”

The son of a print-shop owner, Magruder was born on Nov. 5, 1934, in New York City. He served in the Army from 1954 to 1956 and received a bachelor’s degree in political science from Williams College in 1958 and an MBA from the University of Chicago in 1963.

Magruder was author of “An American Life: One Man’s Road to Watergate,” a 1974 book he wrote while awaiting sentencing; and “From Power to Peace,” a 1978 book about his Christian faith.

Magruder is survived by his children, Whitney, Justin, Tracy and Stuart; and nine grandchildren.

McLellan is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.