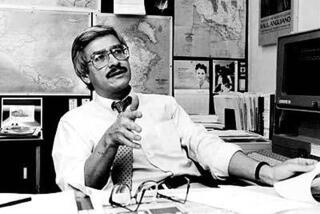

Jaime Escalante dies at 79; math teacher who challenged East L.A. students to ‘Stand and Deliver’

Jaime Escalante, the charismatic former East Los Angeles high school teacher who taught the nation that inner-city students could master subjects as demanding as calculus, died Tuesday. He was 79.

The subject of the 1988 film “Stand and Deliver,” Escalante died at his son’s home in Roseville, Calif., said actor Edward James Olmos, who portrayed the teacher in the film. Escalante had bladder cancer.

“Jaime didn’t just teach math. Like all great teachers, he changed lives,” Olmos said earlier this month when he organized an appeal for funds to help pay Escalante’s mounting medical bills.

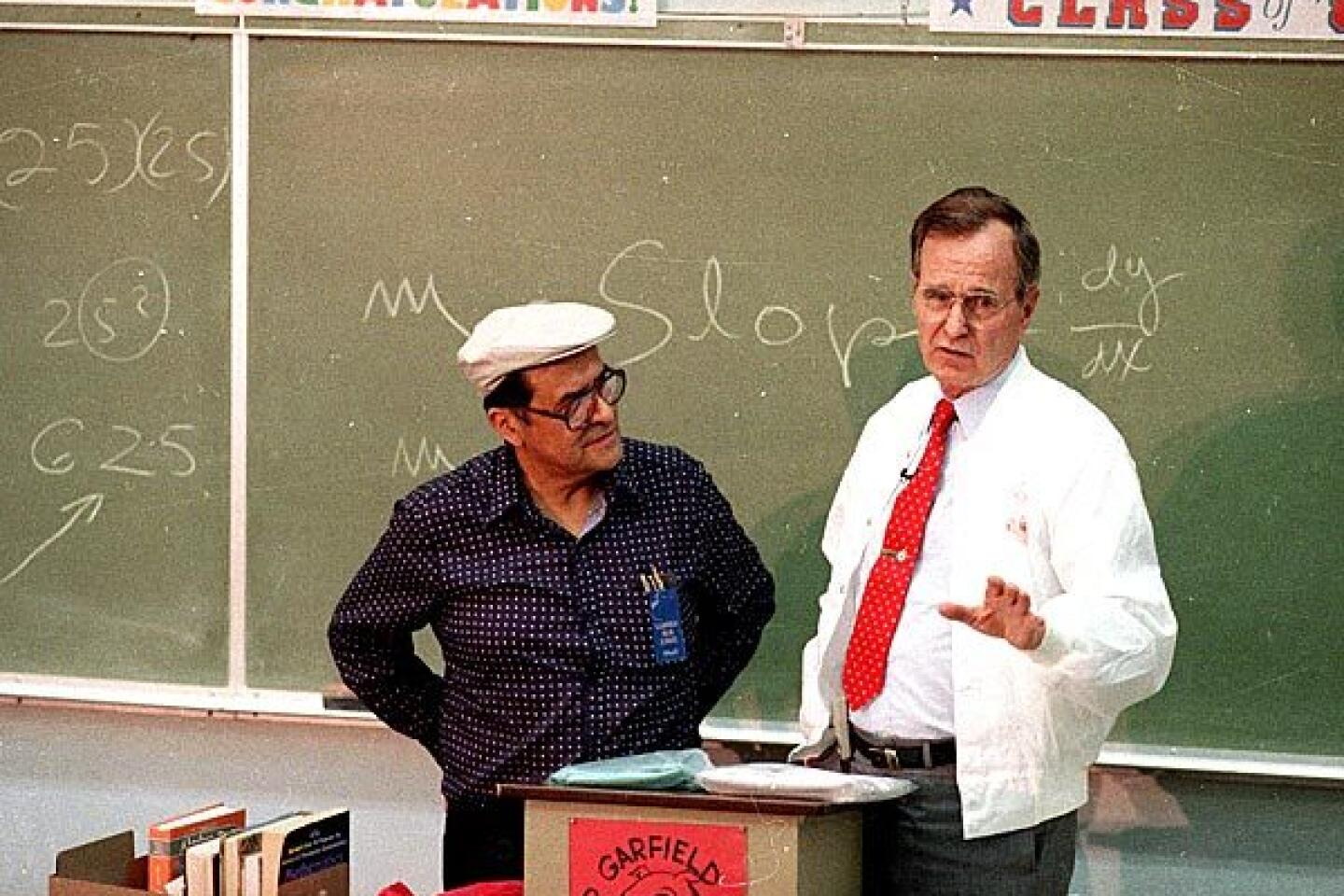

Escalante gained national prominence in the aftermath of a 1982 scandal surrounding 14 of his Garfield High School students who passed the Advanced Placement calculus exam only to be accused later of cheating.

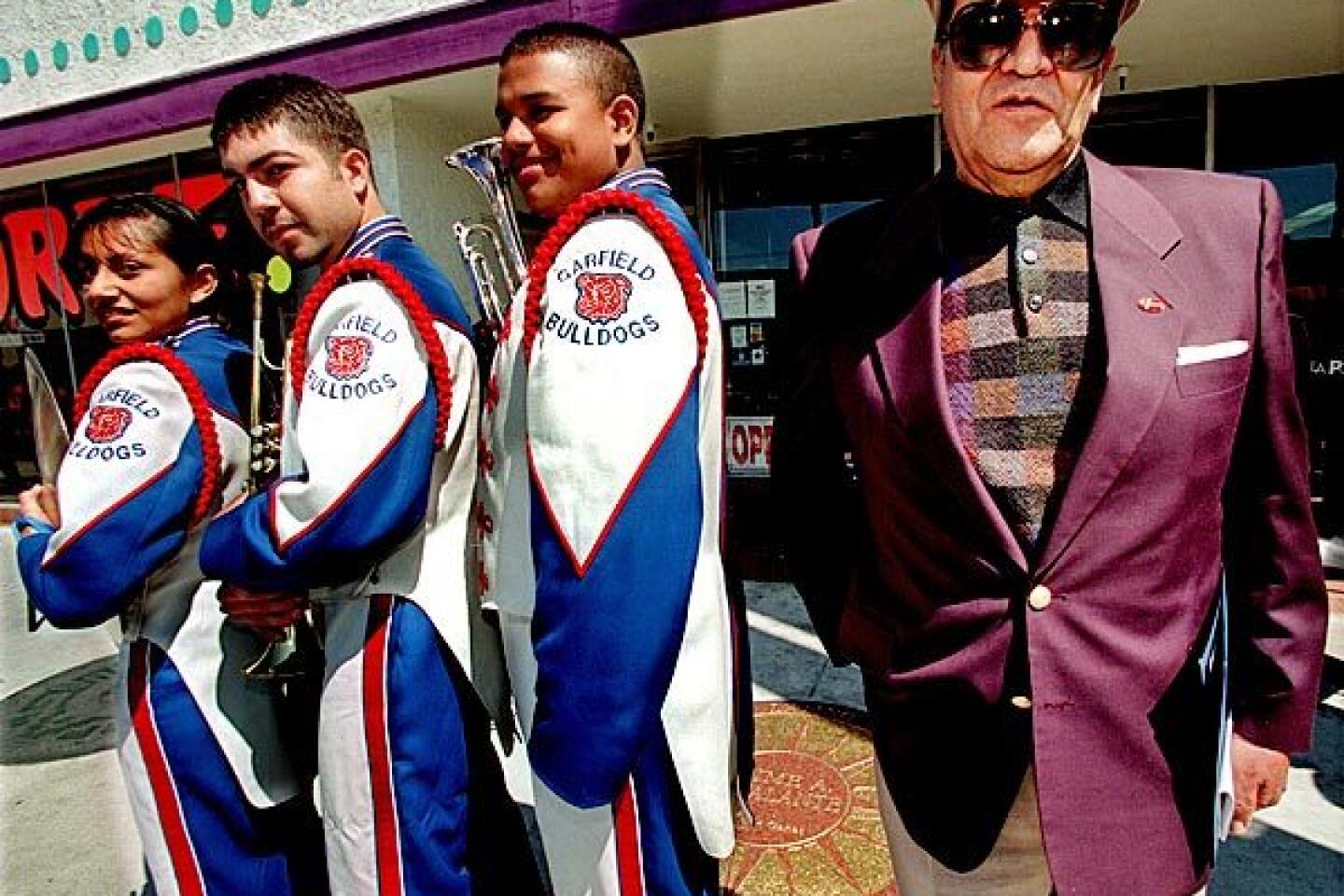

The story of their eventual triumph -- and of Escalante’s battle to raise standards at a struggling campus of working-class, largely Mexican American students -- became the subject of the movie, which turned the balding, middle-aged Bolivian immigrant into the most famous teacher in America.

Passionate teacher

Escalante was a maverick who did not get along with many of his public school colleagues, but he mesmerized students with his entertaining style and deep understanding of math. Educators came from around the country to observe him at Garfield, which built one of the largest and most successful Advanced Placement programs in the nation.

“Jaime Escalante has left a deep and enduring legacy in the struggle for academic equity in American education,” said Gaston Caperton, former West Virginia governor and president of the College Board, which sponsors the Scholastic Assessment Test and the Advanced Placement exams.

“His passionate belief [was] that all students, when properly prepared and motivated, can succeed at academically demanding course work, no matter what their racial, social or economic background. Because of him, educators everywhere have been forced to revise long-held notions of who can succeed.”

Escalante’s rise came during an era decried by experts as one of alarming mediocrity in the nation’s schools. He pushed for tougher standards and accountability for students and educators, often irritating colleagues and parents along the way with his brusque manner and uncompromising stands.

He was called a traitor for his opposition to bilingual education. He said the hate mail he received for championing Proposition 227, the successful 1998 ballot measure to dismantle bilingual programs in California, was a factor in his decision to retire that year after leaving Garfield and teaching at Hiram Johnson High School in Sacramento for seven years.

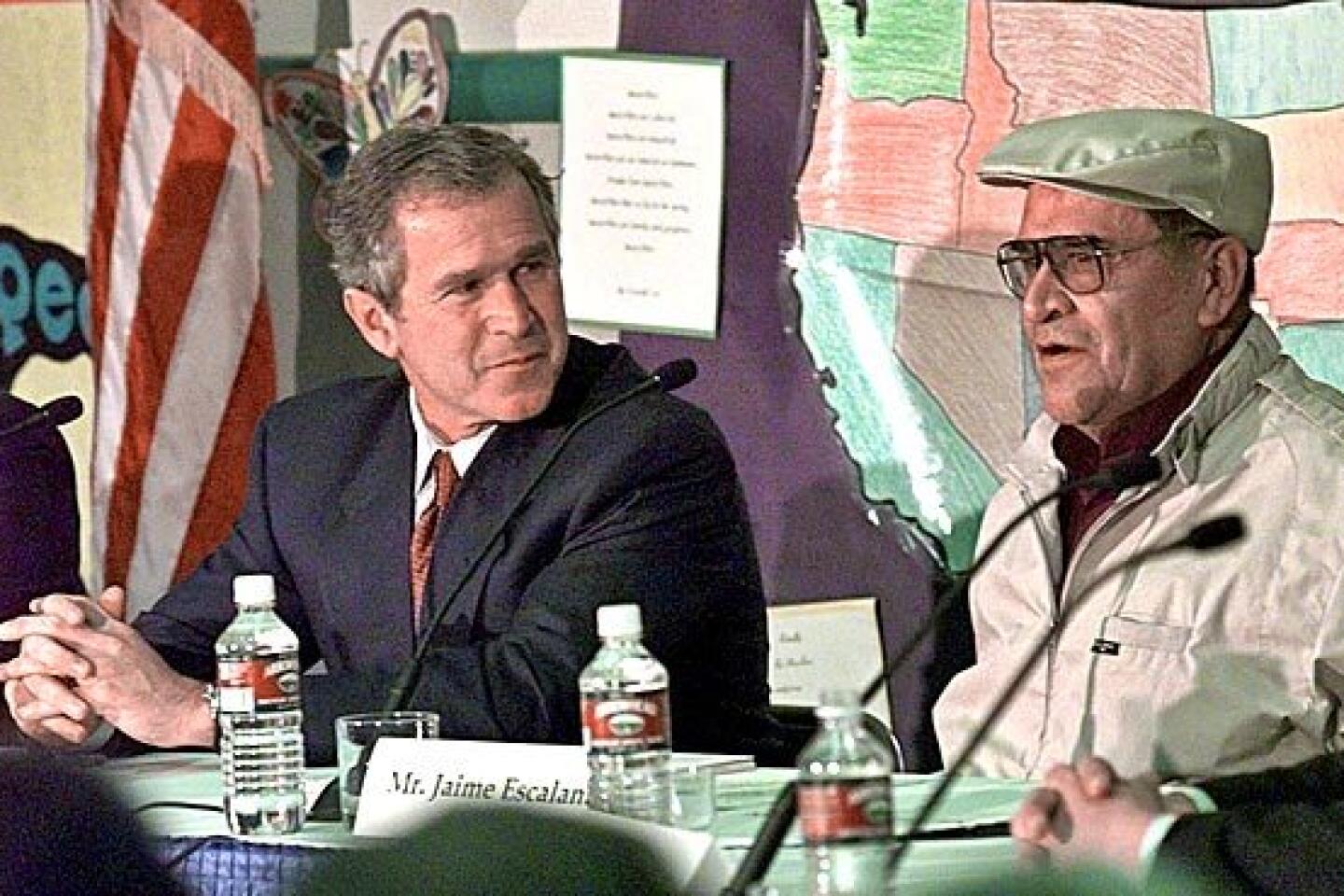

He moved back to Bolivia, where he propelled himself into a classroom again, apparently intent on fulfilling a vow to die doing what he knew best -- teach. But he returned frequently to the United States to speak to education groups and continued to ally himself with conservative politics. He considered becoming an education advisor to President George W. Bush, and in 2003 signed on as an education consultant for Arnold Schwarzenegger’s gubernatorial campaign in California.

Escalante was born Dec. 31, 1930, in La Paz, Bolivia, and was raised by his mother after his parents, both schoolteachers, split when he was about 9. He attended a well-regarded Jesuit high school, San Calixto, where his quick mind and penchant for mischief often got him into trouble.

After high school, he served in the army during a short-lived Bolivian rebellion. Although he had toyed with the idea of attending engineering school in Argentina, he wound up enrolling at the Bolivian state teachers college, Normal Superior. Before he graduated, he was teaching at three top-rated Bolivian schools. He also married Fabiola Tapia, a fellow student at the college.

At his wife’s urging, Escalante gave up his teaching posts for the promise of a brighter future in the United States for their firstborn, Jaime Jr. (A second son, Fernando, would follow.) With $3,000 in his pocket and little more than “yes” and “no” in his English vocabulary, Escalante flew alone to Los Angeles on Christmas Eve 1963. He was 33.

His wife and son later joined him in Pasadena, where his first job was mopping floors in a coffee shop across the street from Pasadena City College, where he enrolled in English classes. Within a few months, he was promoted to cook, slinging burgers by day and studying for an associate’s degree in math and physics by night. That led to a better-paying job as a technician at a Pasadena electronics company, where he became a prized employee. But the classroom still beckoned to the teacher inside him. He earned a scholarship to Cal State Los Angeles to pursue a teaching credential. In the fall of 1974, when he was 43, he took a pay cut to begin teaching at Garfield High at a salary of $13,000.

“My friends said, ‘Jaime, you’re crazy.’ But I wanted to work with young people,” he told The Times. “That’s more rewarding for me than the money.”

When he arrived at the school, he was dismayed to learn he had been assigned to teach the lowest level of math. He grew unhappier still when he discovered how watered-down the math textbooks were -- on a par with fifth-grade work in Bolivia. Faced with unruly students, he began to wish for his old job back.

Motivating students

But Escalante stayed, soon developing a reputation for turning around hard-to-motivate students. By 1978, he had 14 students enrolled in his first AP calculus class. Of the five who survived his stiff homework and attendance demands, only two earned passing scores on the exam.

But in 1980, seven of nine students passed the exam; in 1981, 14 of 15 passed.

In 1982, he had 18 students to prepare for the academic challenge of their young lives.

At his insistence, they studied before school, after school and on Saturdays, with Escalante as coach and cheerleader. Some of them lacked supportive parents, who needed their teenagers to work to help pay bills. Other students had to be persuaded to spend less time on the school band or in athletics. Yet all gradually formed an attachment to calculus and to “Kimo,” their nickname for Escalante, inspired by Tonto’s nickname for the Lone Ranger, Kemo Sabe.

Escalante was hospitalized twice in the months leading up to the AP exam. He had a heart attack while teaching night school but ignored doctors’ orders to rest and was back at Garfield the next day.

Then he disappeared one weekend to have his gallbladder removed. As Washington Post reporter Jay Mathews recounted in his 1988 book, “Escalante: The Best Teacher in America,” the hard-driving teacher turned the health problem into another weapon in his bag of tricks. “You burros give me a heart attack,” he repeatedly told his students when he returned. “But I come back! I’m still the champ.”

The guilt-making mantra was effective. One student said, “If Kimo can do it, we can do it. If he wants to teach us that bad, we can learn.”

The Advanced Placement program qualifies students for college credit if they pass the exam with a score of 3 or higher. For many years it was a tool of the elite; the calculus exam, for example, was taken by only about 3% of American high school math students when Escalante revived the program at Garfield in the late 1970s.

In 1982, a record 69 Garfield students were taking AP exams in various subjects, including Spanish and history. Escalante’s calculus students took their exam in May under the watchful eye of the school’s head counselor. The results, released over the summer, were stunning: All 18 of his students passed, with seven earning the highest score of 5.

But the good news quickly turned bad.

Testing controversy

The Educational Testing Service, which administers the exam, said it had found suspicious similarities in the solutions given on 14 exams. It invalidated those scores.

The action angered the students, who thought the service would not have questioned their scores if they were white. But this was Garfield, a school made up primarily of lower-income Mexican Americans that only a few years earlier had nearly lost its accreditation. “There’s a tremendous amount of feeling that the Hispanic is incapable of handling higher math and science,” Escalante reflected later in an interview with Newsday.

He, like many in the Garfield community, feared the students were victims of a racist attack, a charge that Educational Testing Service strongly denied. Two of the students told Mathews of the Washington Post that some cheating had occurred, but they later recanted their confessions.

Vindication came in a retest. Of the 14 accused of wrongdoing, 12 took the exam again and passed.

After that, the numbers of Garfield students taking calculus and other Advanced Placement classes soared. By 1987, only four high schools in the country had more students taking and passing the AP calculus exam than Garfield.

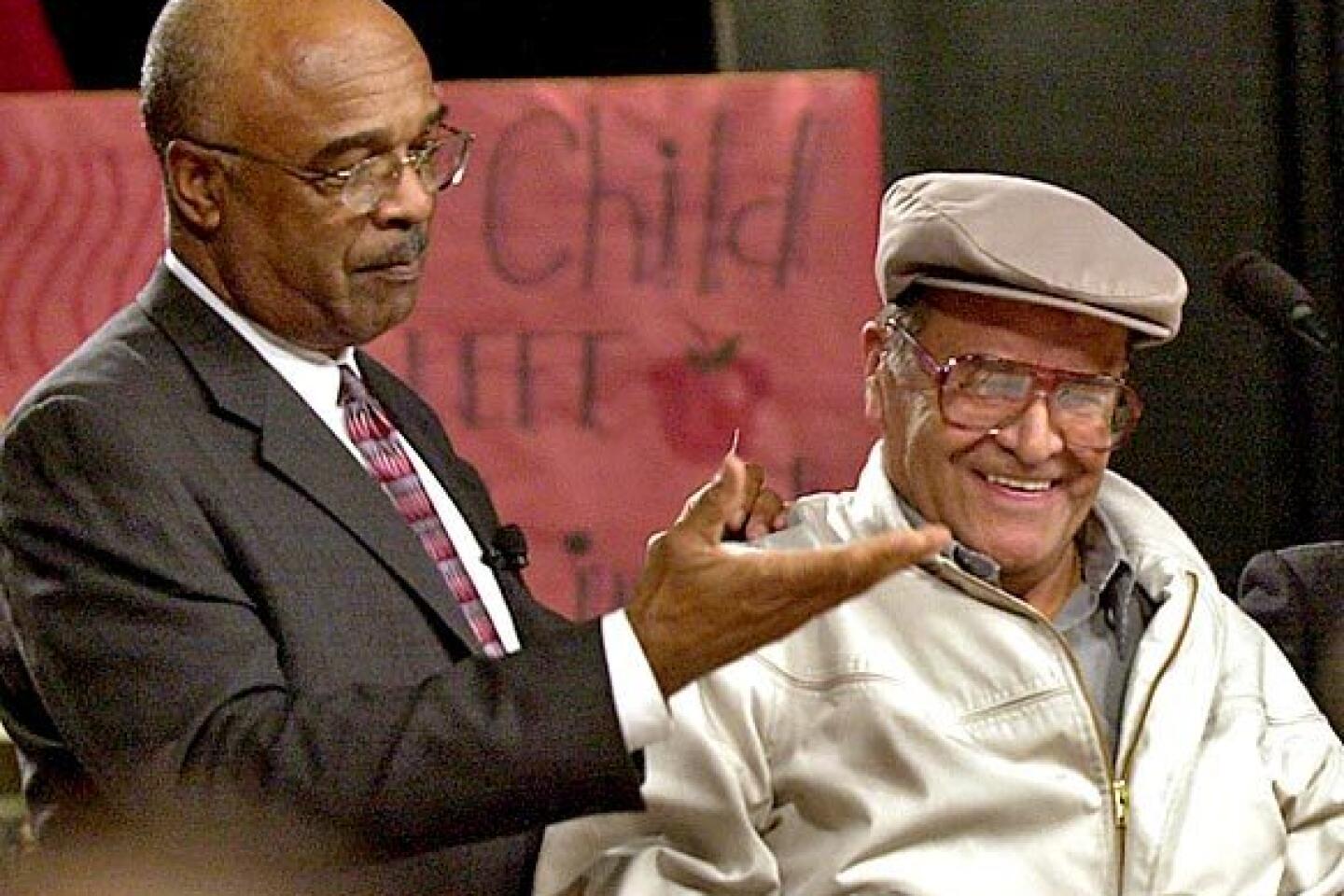

Escalante’s dramatic success raised public consciousness of what it took to be not just a good teacher but a great one. One of the most astute analyses of his classroom style came from the actor who shadowed him for days before portraying him in “Stand and Deliver.”

“He’s the most stylized man I’ve ever come across,” Olmos, who received an Oscar nomination for his performance, told the New York Times in 1988. “He had three basic personalities -- teacher, father-friend and street-gang equal -- and he would juggle them, shift in an instant. . . . He’s one of the greatest calculated entertainers.”

Ultimate performer

Escalante was the ultimate performer in class, cracking jokes, rendering impressions and using all sorts of props -- from basketballs and wind-up toys to meat cleavers and space-alien dolls -- to explain complex mathematical concepts.

Sports analogies abounded. A perfect parabola, for instance, was like a sky-hook by Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. “Calculus Does Not Have To Be Made Easy -- It Is Easy Already,” read a banner Escalante kept in his classroom.

In 1991, he packed up his bag of tricks and quit Garfield, saying he was fed up with faculty politics and petty jealousies.

He headed to Hiram Johnson High with the intention of testing his methods in a new environment.

But in seven years there, he never had more than about 14 calculus students a year and a 75% pass rate, a record he blamed on administrative turnover and cultural differences.

At Garfield, where the pass rate was above 90% when he left, his success was aided by a supportive principal, Henry Gradillas, and talented colleagues, including award-winning calculus teacher Ben Jimenez.

Return to Bolivia

Thirty-five years after leaving Bolivia for his journey into teaching fame, Escalante went home.

He settled with his wife in her hometown of Cochabamba and became a part-time mathematics professor at the Universidad del Valle, and was still teaching calculus in Bolivia in 2008.

He returned to the United States frequently to visit his son and give motivational speeches.

He made his last trip to the U.S. to seek treatment for the cancer that had left him unable to walk or speak above a whisper.

This month, as he gave himself over to a Reno clinic’s regimen of pills, teas and ointments, many of his former students gathered at Garfield to raise money.

Unpopular with fellow teachers, he won few major teaching awards in the United States. He liked to be judged by his results, a concept still resisted by the majority of his profession.

As he faced death, it was still the results that mattered to him -- the young minds he held captive three decades ago who today are engineers, lawyers, doctors, teachers and administrators.

“I had many opportunities in this country, but the best I found in East L.A.,” he said in one of his last interviews. “I am proudest of my brilliant students.”

Escalante is survived by his wife, his sons and six grandchildren.

Times staff writer Robert J. Lopez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.