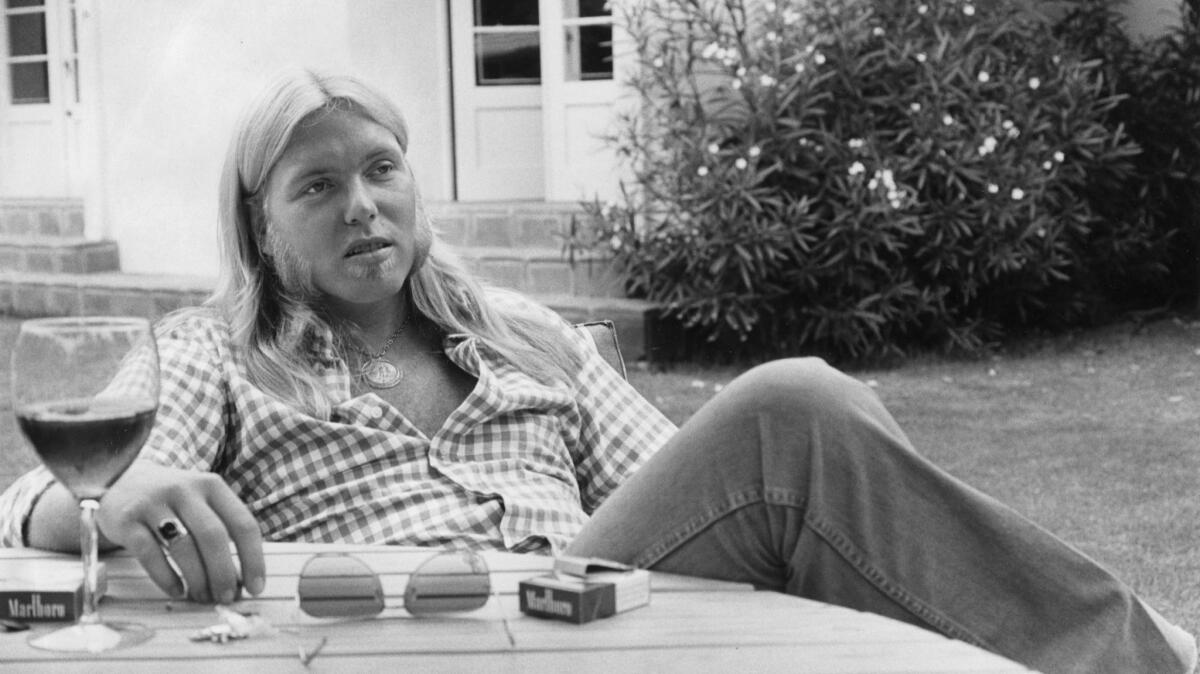

Gregg Allman dies at 69; Southern rock trailblazer co-founded band marked by tragedy

It began like a blues lyric: Gregg Allman hustled up a paper route and used the money to buy a $21.95 Silvertone guitar from Sears. He and his brother, Duane, fought over it until their mother quieted them with a second one. Duane could play like lightning, which meant Gregg, despite a voice of scrape and rasp, was going to have to sing.

“My brother, Duane, could not sing,” Gregg told the Chicago Sun-Times in 2013. “He said, ‘You have to learn to do something.’ So I started to sing. I have a reel-to-reel tape recording of my third night attempting to sing. It sounded atrocious.”

For the record:

9:40 p.m. May 27, 2017An earlier version of this article misspelled the first name of Danielle Galliano as Danille.

Those early recordings were the seeds that would help send the Allman Brothers Band to prominence with a hard-churning brand of soulful Southern rock that rattled the 1960s and ’70s. The brothers created a brash, uncompromising sound that exploded into a blend of wild-living, jazz and blues that would influence groups such as the Marshall Tucker Band and Lynyrd Skynyrd.

Gregg Allman died of liver cancer Saturday at 69, according to his manager Michael Lehman. A statement posted on his official website said Allman, who had a successful liver transplant in 2010 and had canceled concerts in recent years as he battled a variety of health issues, “passed away peacefully at his home in Savannah, Ga.

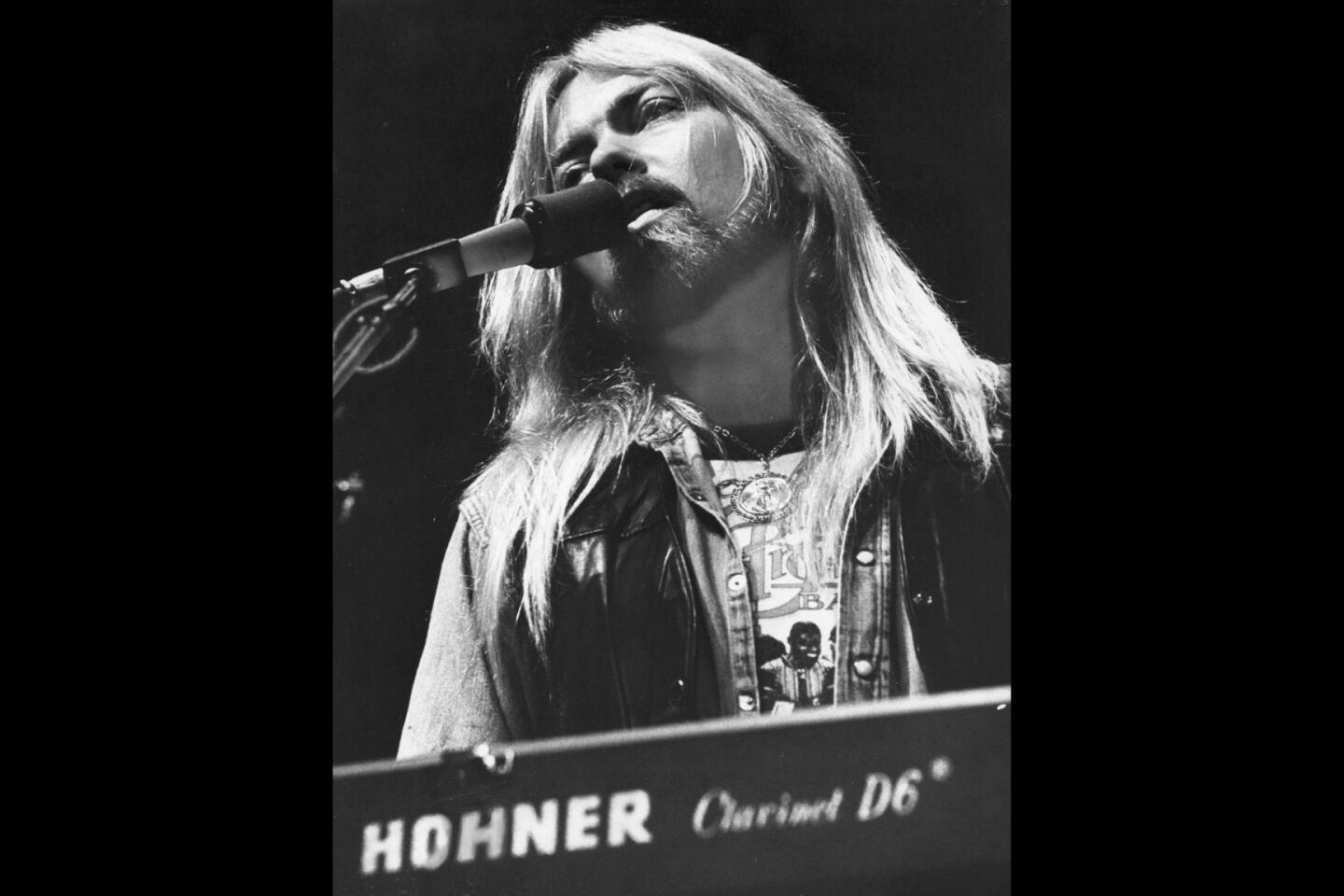

With Allman as the frontman, Duane on slide guitar and not one but two drummers, the group was a kinetic live band, often improvising versions of songs like “Midnight Rider,” “Whipping Post” and “Stormy Monday.” Tinged with country and owing allegiance to Southern black blues, their music sounded as if it had bloomed from bogs and red clay. Allman’s voice matured with sadness, scowl, heartbreak and roadhouse redemption.

“I have lost a dear friend and the world has lost a brilliant pioneer in music,” said Lehman, adding that Allman’s new album “Southern Blood” is scheduled for release in September. “We got finished tracks sent yesterday so Gregg got to hear them. He heard them right before he passed away. He was so happy…. He did what he wanted until the end.”

Considered a “blues everyman,” Allman was the lead singer, organist and primary songwriter of the group, which he formed with Duane in 1969. There have been several iterations since, but the original troupe consisted of the brothers, guitarist Dickey Betts, bassist Berry Oakley and drummers Butch Trucks and Jai Johanny Johanson.

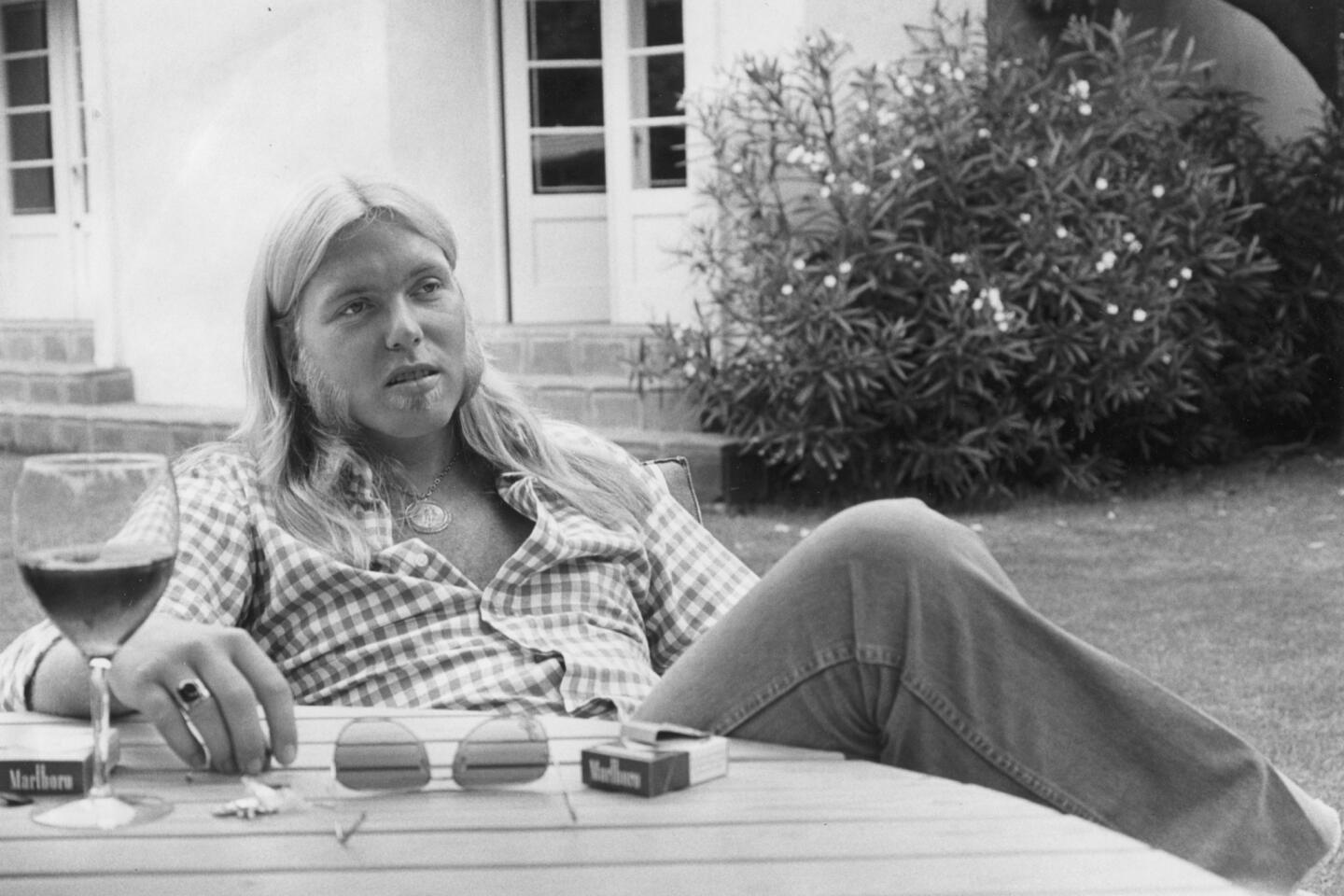

With a hulking presence and an iconoclasts’s defiance, Allman, whose key influence was soul singer Little Milton, was known as much for his personal travails as his music. His life was inlaid with tragedy and rough times, from the deaths of band members (his brother and Oakley died in similar motorcycle accidents and, more recently, Trucks committed suicide), six failed marriages (one to singer and actress Cher), legal disputes and publicized battles with drugs, alcohol and health problems

Allman and his bandmates became such a cautionary tale about the hard-living rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle that they served as source material for the band depicted in Cameron Crowe’s 2000 rock film “Almost Famous.”

“Sure, there have been [difficult times], but I’ve had lots of good times, too, and that’s what I think of when I look back. If I just thought about the bad things, I’d probably be in the rubber room,” Allman told The Times in 1987. “There’s a great comfort in the music itself…. It helps get you through the darkest times. I hope on my death bed that I’m learning a new chord or writing a new song.”

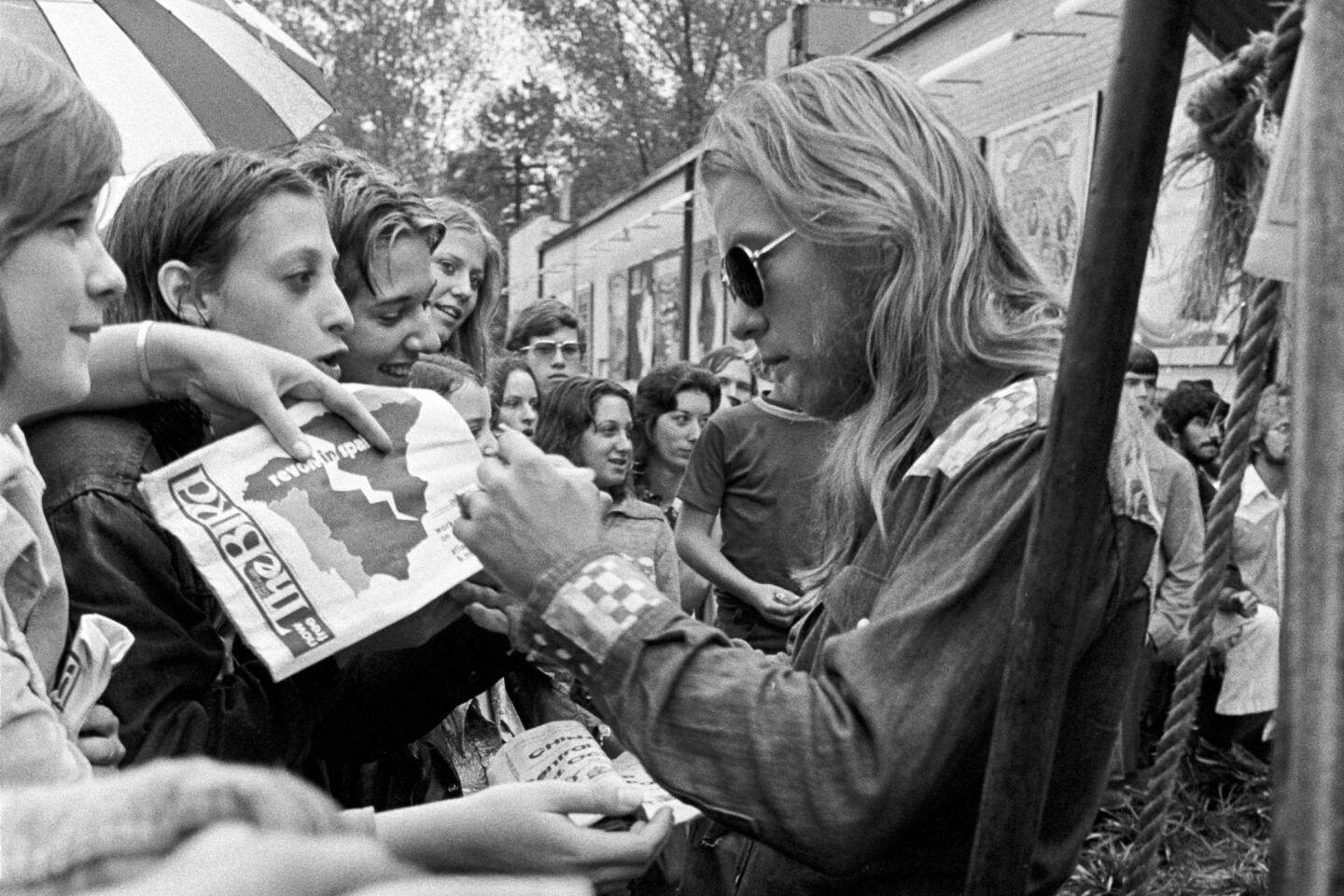

With several career highs, such as the band’s highly regarded 1971 live album “Allman Brothers at Fillmore East,” Allman was democratic about where he played, both with the band and by himself, be it a biker club or an arena. He averaged more than 150 shows a year late into his career.

“I care more about playing … playing well ... than about being up on the charts somewhere and it doesn’t matter the size of the hall,” he told The Times. “When I look back, some of the greatest gigs were at the Fillmore, but some of the best playing was at rehearsals. I’ve always tried to play every night as if it was my last show ... as if the Russians were in Key West and headin’ our way.”

Born Dec. 8, 1947, in Nashville, Gregory LeNoir Allman was the younger son of Willis Turner Allman and his wife, Geraldine Alice Robbins. His father, who stormed the beaches of Normandy during World War II, was killed by a hitchhiker when Allman was 2 and the family moved to Daytona Beach on Florida’s Atlantic coast. There, he and his brother were inspired by late-night blues broadcasts from a Nashville radio station.

Musical pursuits enveloped the brothers, and in 1960, when the two were teens, they attended a show at Nashville Municipal Auditorium that featured Jackie Wilson, Otis Redding, B.B. King and Patti LaBelle. More than the headliners, they were inspired by the band from Orlando that backed up most of the acts.

Duane “was frozen,” Allman wrote in his 2012 memoir, “My Cross to Bear.” “Nothing on his body moved during the whole concert. I had to poke him a couple of times to make sure he was still there with us. That music was in his heart, and it was in mine too.”

The brothers debuted onstage as part of a YMCA youth group in Daytona, forming their first band – the Misfits – while attending a military academy in Tennessee. In 1963, the brothers returned to Florida and formed the Shufflers, followed by the Escorts and then the Allman Joys. As the Vietnam War intensified, Allman decided to avoid the draft by shooting himself in the foot — another reason he was better suited to sit at a keyboard than roam the stage with a guitar.

After recording a regional hit song called “Spoonful,” the brothers moved to Los Angeles and recorded two albums for Liberty Records under the band name Hour Glass. Unhappy with their creative output, Duane headed back home and later convinced Gregg to return and join a new group he was putting together. There was one catch: With Duane and Betts, there was no room for another guitarist. Duane, ranked by Rolling Stone as one of the best guitar players ever, urged his brother to take up the organ, specifically a Hammond B3. He agreed and hitchhiked east.

“They hoped like hell I could play it,” he said of his conversion from guitar to organ. “I showed them my 22 songs, one was ‘Dreams,’ the other was ‘It’s Not My Cross to Bear.’ I was in, I belonged, which was great because I’d just spent the last 14 months in California listening to my hair grow. Me and Beverly Hills, it’s not my habitat.”

The group released its critically acclaimed, self-titled debut album in 1969. Their second album, “Idlewild South,” which featured his composition “Midnight Rider,” had much better sales. Increasingly, the group became known for its powerful live shows, often stretching songs into 20-minute jam fests.

Their third album, the monster LP “Allman Brothers at Fillmore East” — recorded at the legendary New York venue — established the group as a national force. The band was midway into recording the eventual follow-up, “Eat a Peach,” when Duane was killed in a motorcycle accident in 1971. His brother’s death took a toll on Gregg and the band’s lineup soon began to change.

“We were like Lewis and Clark, man — we were musical adventurers, explorers,” Allman wrote in his memoir. “We were one for all and all for one.”

Oakley died in a similar motorcycle accident a year later and at the same age as Duane (the two are buried next to each other in Macon, Ga). The band followed up “Eat a Peach” in 1973 with “Brothers and Sisters,” a commercial success that included the hit “Ramblin’ Man.” While the group endured as one of the most popular rock bands in the U.S., the pressures of success and the excesses of the road took a toll.

Between tours, Allman performed solo and released several albums before having a surprise hit in 1987 with “I’m No Angel,” a slickly produced album that sold well. But Allman had fallen out of favor with his bandmates after testifying against his personal road manager, John “Scooter” Herring, who was charged with multiple counts of conspiracy to distribute narcotics. Allman had been granted immunity in exchange for his testimony, and several members of the band saw it has an act of betrayal. For Betts, Allman’s testimony poisoned the water, and the Allman Brothers Band lineup began to unravel.

A man of excesses, Allman, who in later years wore his graying hair in a ponytail, was apparently little different with women. The band’s early road manager charted the legal age of consent in every state and gave a copy to each band member.

“I would have women in four or five different rooms,” Allman boasted in his book. “Mind you, I wouldn’t lie to anybody; I’d just say, ‘I’ll be right back.’ ”

After having his first child, Michael Sean, with ex-girlfriend Mary Lynn Sutton, he married Shelley Kay Winters in 1971 and had a second son, Devon, the lead singer for the blues group Honeytribe. In 1973, he married Janice Mulkey and then Cher two years later. The two had a son, Elijah Blue, now a singer and guitarist.

Allman and Cher divorced in 1979 and he married Julie Bindas, with whom he had daughter Delilah Island, before they divorced in 1984. He then married Danielle Galliano and, after a 1994 divorce, married Stacey Fountain in 2001. He also had a daughter, Layla Brooklyn, with Shelby Blackburn, a former girlfriend. He married Shannon Williams late last year.

The Allman Brothers Band got back together in the early 1980s, but Allman said it was a hollow experience. “The money was still there ... and the fans, but that didn’t impress me,” he told The Times. “I could tell that none of us were really enjoying it anymore.”

Though Allman said the group went through a staggering amount of cocaine and he went to rehab for heroin addiction, he said his personal demon was alcohol. “Finally I got to a point where I said, ‘Man, what do you want to do with the rest of your life? Keep going into rehab centers or play your music?’ ”

Allman said he got sober in 1995, the same year the Allman Brothers Band was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

In the late 1990s, he tried his hand at acting and appeared in 1991’s “Rush” and HBO’s “Tales from the Crypt.” The big-screen adaptation of “Rush” featured Allman as the sullen Will Gaines, a reputed drug kingpin. Aware of his personal substance abuse history, working on a drug movie that was set in the 1970s didn’t bother him, he said in 1991, because his “problems like that ended a long time ago.”

In 2011, he recorded “Low Country Blues,” his 11th studio album. But his later years were marked with health problems and disappointments, such as the uncompleted biopic “Midnight Rider.” Allman had a liver transplant after contracting hepatitis C, which he blamed on a dirty needle that was used during a tattoo session. Then, citing health issues, Allman began canceling concerts with regularity. In early 2017, Allman’s spokesman denied rumors that the musician was under hospice care.

But the Allman Brothers Band, and its newest iterations, continued despite the absence of the band’s namesakes. When asked by Canada’s Globe and Mail in 2012 if the band might actually outlive both Allman brothers, he said, “I’d like to think so … I’d really like to think so.”

Times staff writers Jeffrey Fleishman and Carolina A. Miranda contributed to this report.

Music is the only thing I’ve ever done. The only other ‘job’ I ever had was a paper route and I took that money and bought a guitar.

— Gregg Allman

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour »

From the Archives: How Gregg Allman sobered up, quit smoking and got his groove back »

Follow me: @NardineSaad

MORE OBITUARIES

Chris Cornell, who helped reignite hard rock in the 1990s with Soundgarden, dies at 52

Roger Moore dies at 89; debonair British actor played James Bond in 7 movies

Jam-band musician Col. Bruce Hampton dies after collapsing onstage during 70th birthday concert

UPDATES:

6:45 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details, including cause of death.

This article was originally published at 12:40 p.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.