Italian film, theater and opera director Franco Zeffirelli, known for his over-the-top productions, once described a scene of a father reacting to his son’s desire to work in the theater.

“He just broke everything in sight. Having exhausted the china and glass, he opened a drawer and pulled out a revolver, which he started to wave about.

For the record:

9:10 a.m. June 15, 2019An earlier version of this article misstated the time frame of Los Angeles Opera’s presentation of Zeffirelli’s “Pagliacci.” It was 1996.

“‘I made you, now I’ll unmake you!’”

The scene was not from one of Zeffirelli’s flamboyant movies or operas. It was from his life.

Zeffirelli, 96, whose life, like his productions, was full of grand characters, outsize passions, temperamental rages and torrid love affairs, died Saturday in Rome.

“He left in a peaceful way” after a long illness, his son Luciano told the Associated Press.

Zeffirelli is most widely known for his films, including the 1968 critical and box office hit “Romeo and Juliet” and a 1990 “Hamlet” with Mel Gibson, among other Shakespeare adaptations. His non-Bard movies included a remake of the classic “The Champ” (1979), with Jon Voight; “Tea with Mussolini” (1999) set in his beloved Florence; and his last feature film, “Callas Forever” (2002), which paid homage to his tempestuous friend, opera singer Maria Callas.

Some of his films drew mixed reviews at best, but his opera productions — with massive, opulent sets and onstage casts sometimes numbering in the hundreds, not to mention including animals — are almost invariably audience favorites in the opera houses that can afford them worldwide. At America’s premier opera venue, the Metropolitan Opera in New York, Zeffirelli’s version of Puccini’s “La Boheme” is the most-often presented production in the company’s history.

In 1996 Los Angeles Opera presented his popular production of Leoncavallo’s “Pagliacci,” featuring crowd scenes that included acrobats, jugglers, fire eaters and a live donkey.

Critics complained that his stage productions were excessive, but for Zeffirelli, excess was just a starting point.

“They must always tell me, ‘Stop, is enough, is excessive,’” he told the London Observer in 2003. “But I prefer to go berserk. I will never stop!”

At 83, he created his last major, new opera production, his take on Verdi’s “Aida” that opened the La Scala season in Milan, Italy, in 2006. As usual, Zeffirelli designed the sets and costumes, as well as directed, resulting in an extravaganza that the Telegraph in London described as evoking “the grandeur of ancient Egypt in a riot of golden magnificence.”

On opening night, with Italy’s Prime Minister Romano Prodi and German Chancellor Angela Merkel in the audience, the applause went on for 15 minutes.

“For me, opera is dreams,” Zeffirelli said, “and when I dream I create my own planet.”

He engaged in high-profile feuds and his famous temper didn’t spare even as august a figure as conductor Arturo Toscanini, who caught Zeffirelli’s rage when he interrupted a rehearsal.

In his autumn years, Zeffirelli railed against the nontraditional stagings of young opera directors.

“They say I’m the greatest director of opera in the world,” he told the Independent in 2003. “I’m not the greatest — I’m the only one.”

Even his birth caused a scandal.

Zeffirelli was born Feb. 12, 1923, in the outskirts of Florence. His mother was seamstress and clothes designer Alaide Garosi, and his father was fabric merchant Ottorino Corsi — both of whom were married to others when Zeffirelli was conceived. In fact, Garosi was pregnant with him when she attended her husband’s funeral.

In his 1986 autobiography “Zeffirelli,” he wrote that his parents had “a stormy love affair that scandalized the close community that was Florence sixty years ago.”

His mother meant to give him the name Zeffiretti, meaning “little breezes,” from a Mozart aria, but a clerk misspelled it.

Zeffirelli was 6 when his mother died and he was raised mostly by his aunt. In his second autobiography, published in Italy in 2006 (no English-language version has been published), he revealed he had an early sexual experience with a priest. But Zeffirelli, a lifelong, staunch supporter of the Catholic Church and its hierarchy, did not describe the incident as traumatic.

“Molestation suggests violence and there was no violence at all,” he said in a 2006 Guardian interview.

Although he had several heterosexual affairs beginning when he was 16 — “I was very attractive, very handsome, and a lot of women fell in love with me,” he told the Guardian — his key romantic relationships were with men.

Zeffirelli wrote that he fought on the side of partisans against Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s fascist forces during World War II and was several times in danger. After the war he was planning to have a career as an architect until, in 1945 and back in Florence, he saw the film version of Shakespeare’s “Henry V” directed by and starring Laurence Olivier.

“There was Olivier at the height of his powers and there were the English defending their honor,” he wrote. “I knew then what I was going to do. Architecture was not for me; it had to be the stage.”

He was a lowly 22-year-old assistant scene painter when he met prominent stage and film director Luchino Visconti and they began a nearly decade-long affair. It was a rocky relationship, but through it, Zeffirelli met some of the major stage artists and celebrities of the time, including Callas, Leonard Bernstein, Anna Magnani, Coco Chanel and Tennessee Williams.

And his set designs for productions by Visconti and others brought him notice of his own. His breakout as a director came in 1954 when he was designing sets for a production of Rossini’s “La Cenerentola” (“Cinderella”) at La Scala. When the director became ill, Zeffirelli asked for the job and got it.

His completely revamped production was a “syntheses of past and present, combining 18th-century costumes with a pale, clearly lit palette,” wrote critic Zachary Woolfe in a 2011 London Observer feature. Although Zeffirelli’s stage works are now seen in many quarters as overburdened, he came onto the scene as an innovator.

His stature grew with further productions, especially a 1957 staging in Dallas of Verdi’s “La Traviata,” starring Callas and done as a flashback. And his no-holds-barred 1959 production of Donizetti’s “Lucia di Lammermoor” in London made Joan Sutherland a star.

He triumphed in non-opera theater in London in 1960 with a naturalistic production of “Romeo and Juliet” that starred Judi Dench, then 25, and emphasized the sensuality of the relationship. Although several critics hated its break from tradition — he ordered actors to stress the dramatic nature of Shakespeare’s dialogue rather than its poetry — critic Kenneth Tynan in the Observer hailed it as “a revelation, even perhaps a revolution,” and young theatergoers (and non-theatergoers) lined up for tickets.

Zeffirelli then worked with prominent stage actors such as John Gielgud, Maggie Smith, Ian McKellen and his inspiration, Olivier.

His first major film as a director, “The Taming of the Shrew” (1967), was headlined by two of the biggest stars of the time: Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton.

However, for the 1968 film of “Romeo and Juliet” he insisted on casting teenage unknowns Leonard Whiting and Olivia Hussey, in large part because of their beauty. He again emphasized the sensual nature of the relationship, this time to the point of having them mostly nude in a bedroom scene.

The film, much of which was photographed in a warm glow, was a blockbuster and drew critical raves. Los Angeles Times critic Charles Champlin wrote of “how triumphantly Zeffirelli has infused life and vigor, color and credence, into Shakespeare’s poetic tragedy.”

Some of Zeffirelli’s later films got good notices from critics, especially the two-part “Jesus of Nazareth,” shown on NBC in 1977, and his 1982 film of the Verdi opera “La Traviata. Roger Ebert called his 1990 “Hamlet” with Gibson and Glenn Close “robust and physical and — don’t take this the wrong way — upbeat.”

But Zeffirelli never came close to duplicating the critical success of the “Romeo and Juliet” film. His follow-up big screen effort, “Brother Sun, Sister Moon” (1972) — a kind of flower-child version of the St. Francis of Assisi story — sparked complaints that he emphasized pretty vistas and people more than meaningful content. His “The Champ” (1979) with Voight and a young Ricky Schroder was generally dismissed as an overwrought sudser.

By the time he made “Endless Love” (1981), he seemed to be in a public feud with Hollywood and his conservative views were coming to bear. “We’re fed up with seeing all the beautiful things in life destroyed,” he said in a 1981 Los Angeles Times Times interview on the set of the film. “I want to restore dignity to sex, after all the exploitation by the (film) industry.”

The movie, starring Brooke Shields, did well at the box office but was roundly trashed by critics.

Perhaps the worst reception he got for a film was the biopic “Young Toscanini” (1988), which was roundly booed at the Venice Film Festival and didn’t get a U.S. distributor. Earlier that year he angered many in the film community when he called Martin Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ” ’’truly horrible, completely deranged” on religious grounds.

Zeffirelli didn’t just make political statements. In 1983 he first ran for a seat in the Italian Parliament on the Christian Democratic ticket, but lost. He then swore off politics, but as often happened in his life, later changed his mind, running in 1994 on the ticket of the right-leaning Forza Italia party, headed by his highly controversial billionaire friend, Silvio Berlusconi. This time, Zeffirelli won and was reelected in 1996.

He was a staunch defender of Berlusconi through the former prime minister’s many and varied scandals. Zeffirelli told interviewers that Berlusconi bought him his Rome villa where he lived with his many dogs and continued to entertain, though he outlived most of his famous friends. He adopted two adult men as his sons, and they helped him get around after he became unsteady on his feet, due to what he said was a botched hip replacement.

“I shot all the films I wanted to, while I went back to opera whenever I felt vulnerable and in need of reassurance,” he said in a 2013 China Daily interview. “Opera for me has always been a sort of mother figure, the mother I lost when I was six.”

Colker is a former Times staff writer.

2/33

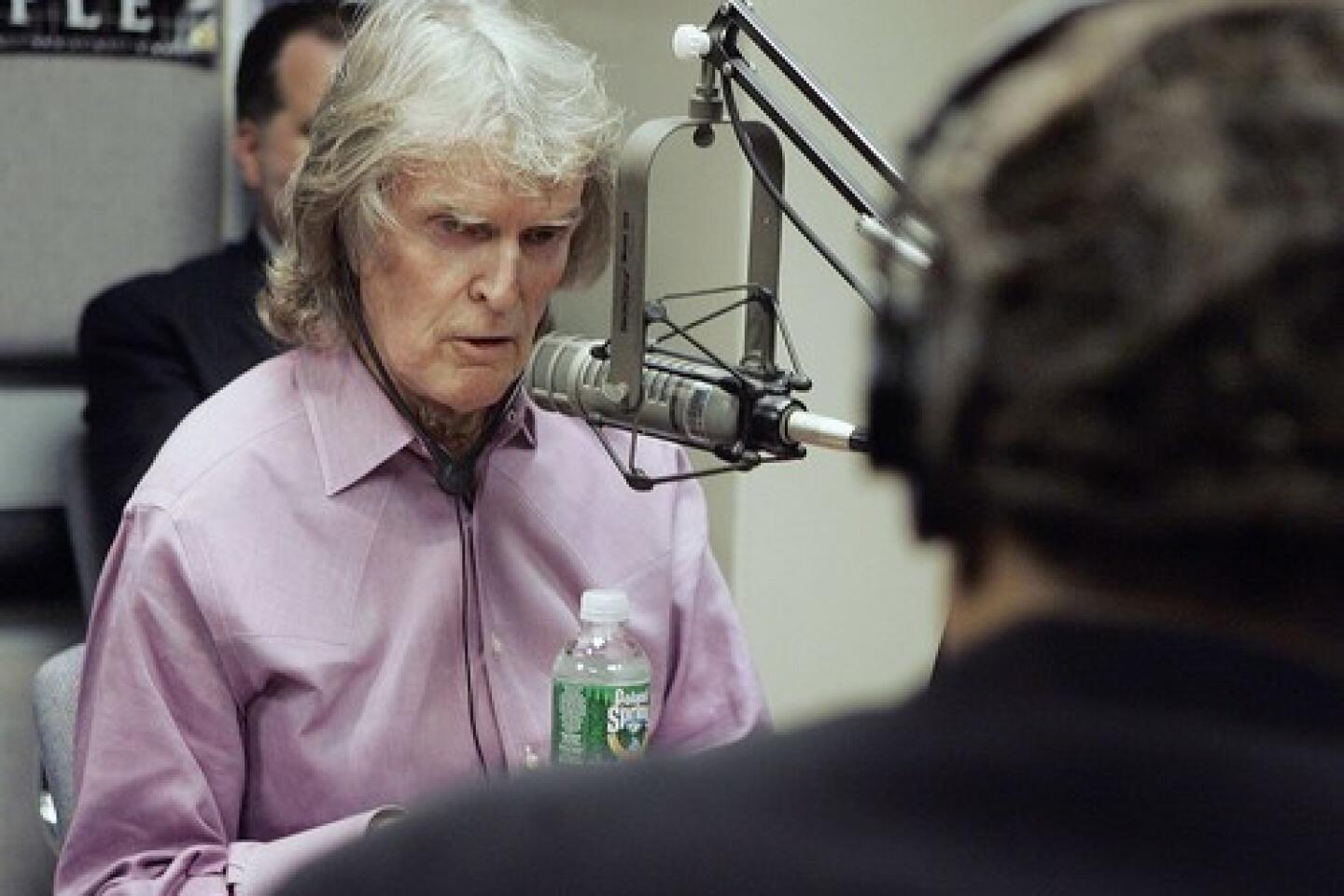

Pioneering shock jock Don Imus was one of radio’s most popular and polarizing figures. Born in Riverside, he became a top broadcaster in New York, but he also sparked a national firestorm in 2007 with a racist remark about the Rutgers University women’s basketball team. He was 79. (Richard Drew / Associated Press)

3/33

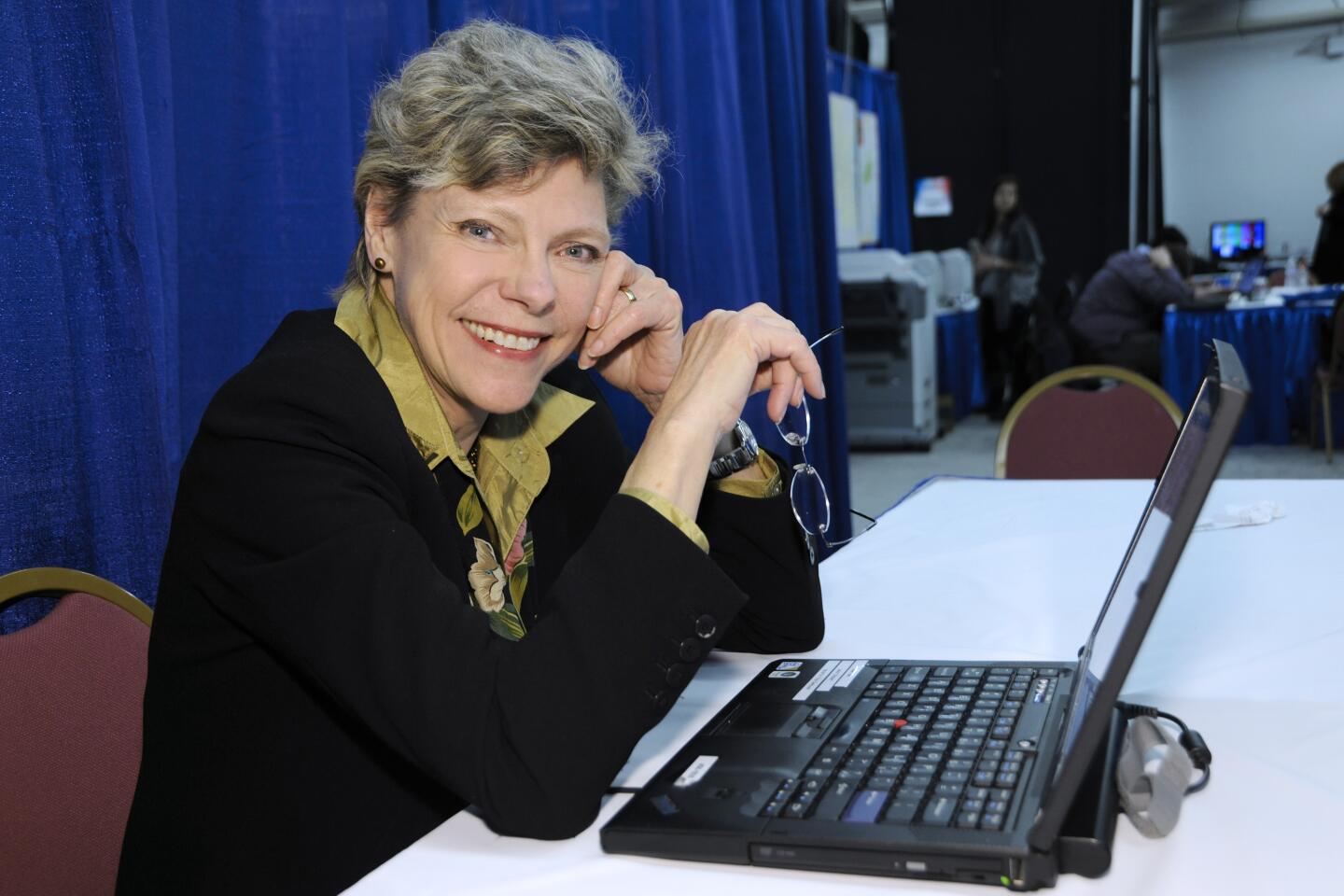

Cokie Roberts covered Washington from Jimmy Carter to Donald Trump for NPR and ABC News. A co-anchor of the ABC Sunday political show “This Week” from 1996 to 2002, Roberts devoted most of her attention to Congress, where her father Hale Boggs was a House majority leader until his death in 1972. She was 75. (Donna Svennevik / Walt Disney Television via Getty)

4/33

T. Boone Pickens followed his father into the oil and gas business and built a reputation as a maverick, unafraid to compete against industry giants. In the 1980s, Pickens sought riches on Wall Street by leading bids to take over big oil companies including Gulf, Phillips and Unocal. Even when he failed to gain control of his targets, he scored huge payoffs by selling shares back to the company and dropping the hostile takeover bid. He was 91. (Riccardo Savi / Getty Images)

5/33

When Robert Mugabe took over as Zimbabwean president in 1980, he was celebrated as a hero in the liberation war against Britain. But after international sanctions, a series of fraudulent elections and an economic collapse sparked by the seizure of white-owned farms, Mugabe become a pariah and retired in 2017 rather than face impeachment. He was 95. (Tsvangirayi Mukwazhi / Associated Press)

6/33

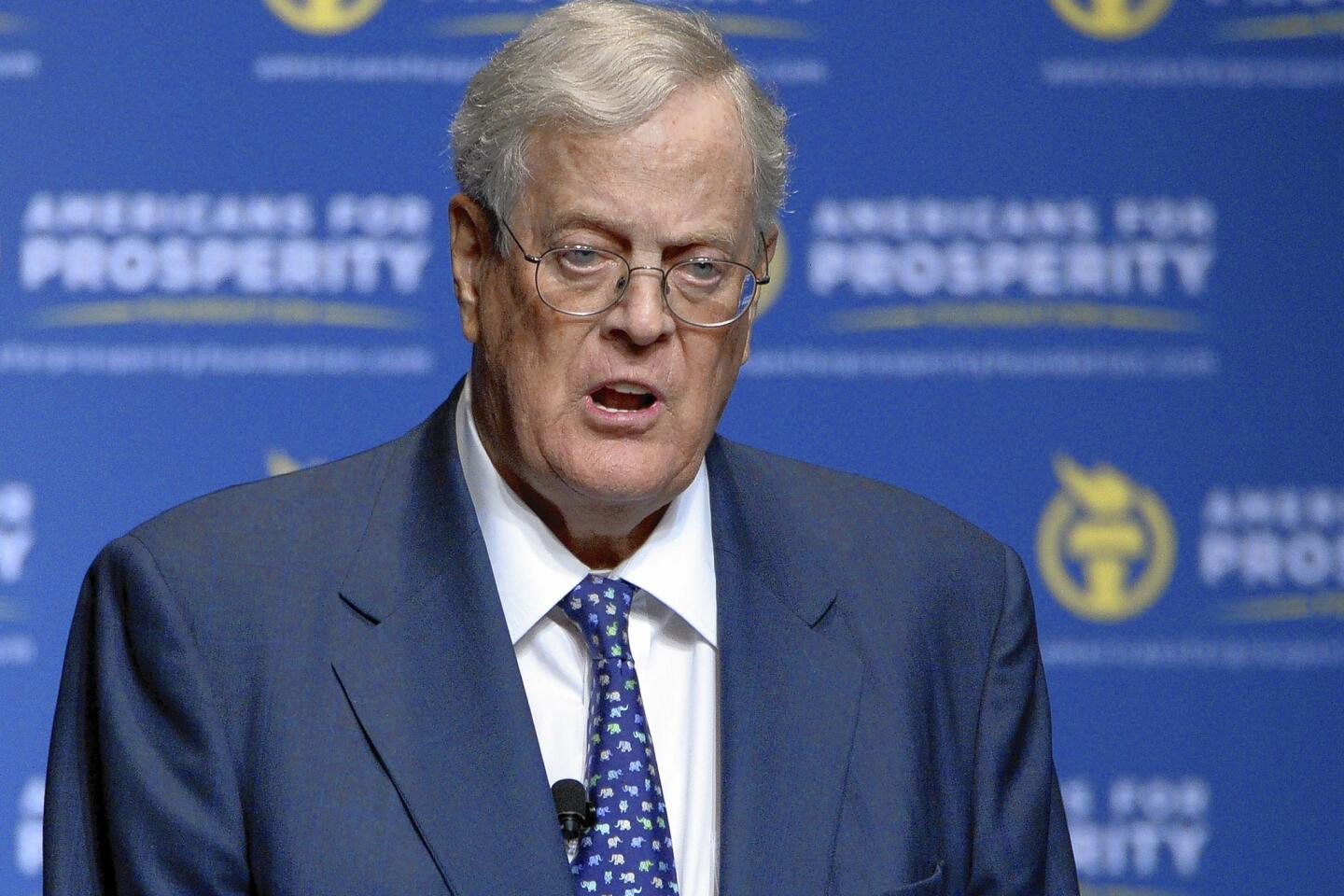

David Koch was the aide de camp to Charles, his older brother, as the two leveraged the family fortune to push American politics to the right. The Koch brothers pushed the boundaries of dark money in politics and fueled a backlash against environmental regulations and government programs such as healthcare and mass transit. He was 79. (Phelan M. Ebenhack / Associated Press)

7/33

Peter Fonda was the son of a classic Hollywood star and a key player in the 1969 countercultural road trip saga “Easy Rider,” which he co-wrote and produced. The screenplay earned Fonda his first Academy Award nomination; his second came in the lead actor category for the 1997 independent film “Ulee’s Gold.” He was 79. (AP)

8/33

Hard-line Chinese premier Li Peng was best-known for ending the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests with a bloody crackdown by troops. A keen political infighter, he spent two decades at the pinnacle of power before retiring in 2002, leaving a legacy of prolonged economic growth and authoritarian control. He was 90. (AP)

9/33

Chris Kraft, shown with President Reagan in 1981, never flew in space but was the creator and longtime leader of NASA’s Mission Control. The legendary engineer served as flight director for all Mercury flights and seven of the Gemini flights, helped design the Apollo missions and later oversaw the beginning of the shuttle era at Johnson Space Center. He died just two days after the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11’s moon landing. He was 95. (AP)

10/33

Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens joined the court as a centrist Republican but emerged in his later years as the leading voice of its liberal bloc. Appointed by President Ford, Stevens played a key role in decisions that preserved a woman’s right to abortion, maintained a strict separation of church and state, and put limits on the death penalty. He was 99. (AP)

11/33

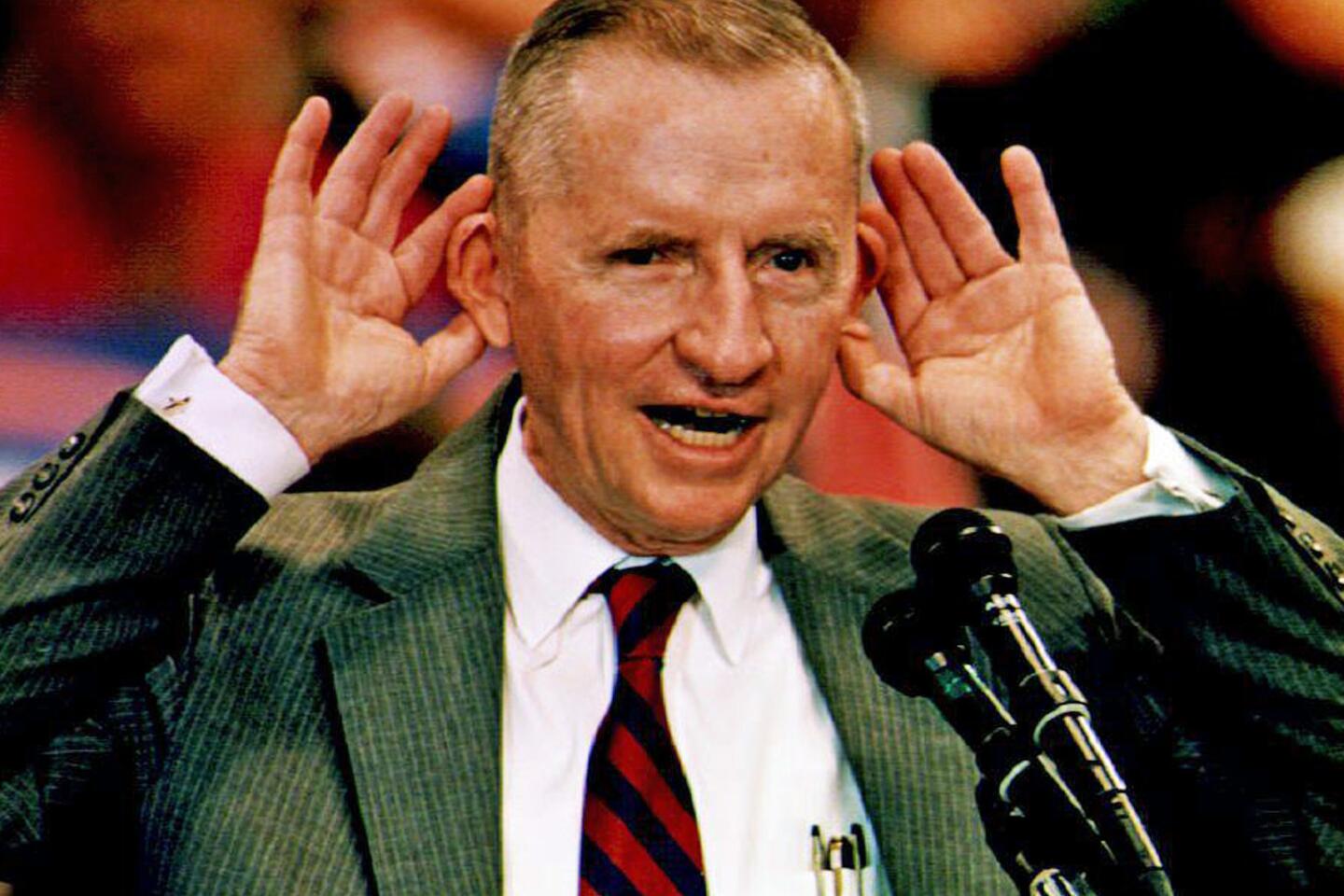

Billionaire Ross Perot blazed across America in the 1990s as a third-party presidential candidate and won nearly 19% of the popular vote in the 1992 election, finishing third behind Democrat Bill Clinton and Republican President George H.W. Bush. The diminutive Texan was an early tech entrepreneur who founded Electronic Data Systems, a computer services company, in 1962 with $1,000 in savings. He was 89.

(Peter Muhly / AFP/Getty Images) 12/33

Pitcher Tyler Skaggs grew up an Angels fan in Santa Monica and joined the organization as a first-round draft pick. He battled injuries throughout his career but started 24 games last season and showed signs of dominance this year. He was 27.

(Charlie Riedel / AP) 13/33

Judith Krantz wrote blockbuster romance novels including “Scruples” and “Princess Daisy” that sold more than 80 million copies worldwide. Her books have been translated into more than 50 languages, and seven have been adapted as TV miniseries, with her late husband, Steve Krantz, serving as executive producer for most. She was 91.

(Aaron Rapoport / Getty Images) 14/33

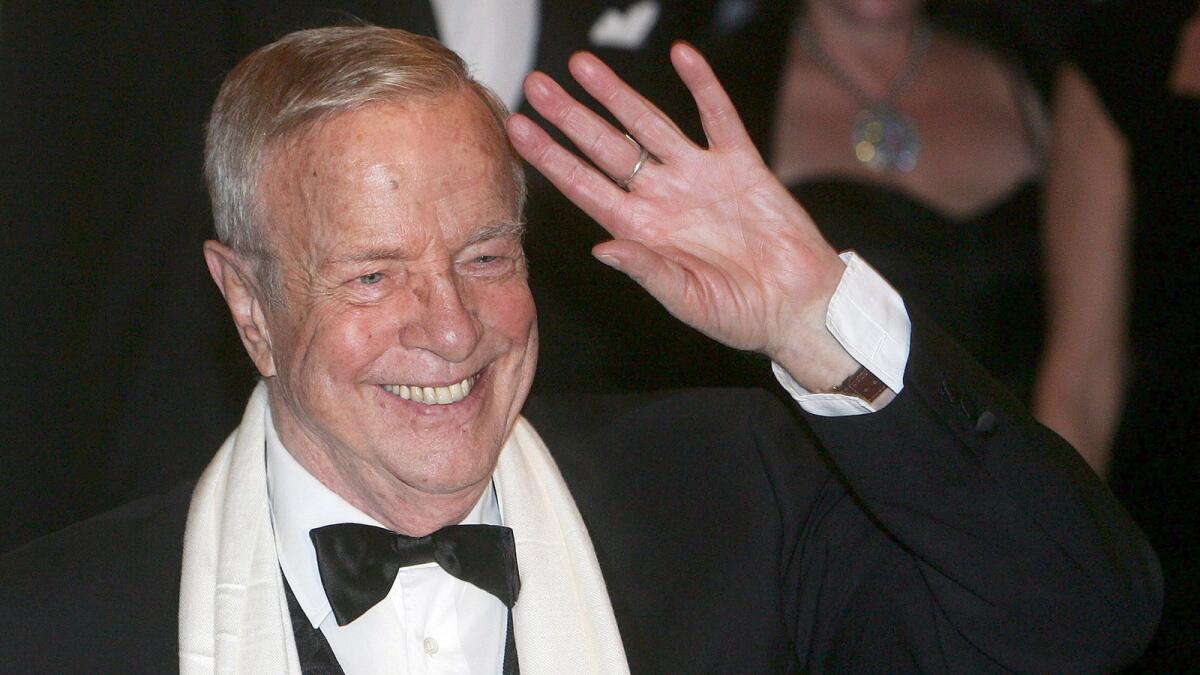

Italian director Franco Zeffirelli was best-known for his films, including the 1968 critical and box office hit “Romeo and Juliet” and a 1990 “Hamlet” with Mel Gibson. His massive opera productions included a version of Puccini’s “La Boheme” that became the most-often presented production in the Metropolitan Opera’s history. He was 96.

(Paolo Cocco / AFP/Getty Images) 15/33

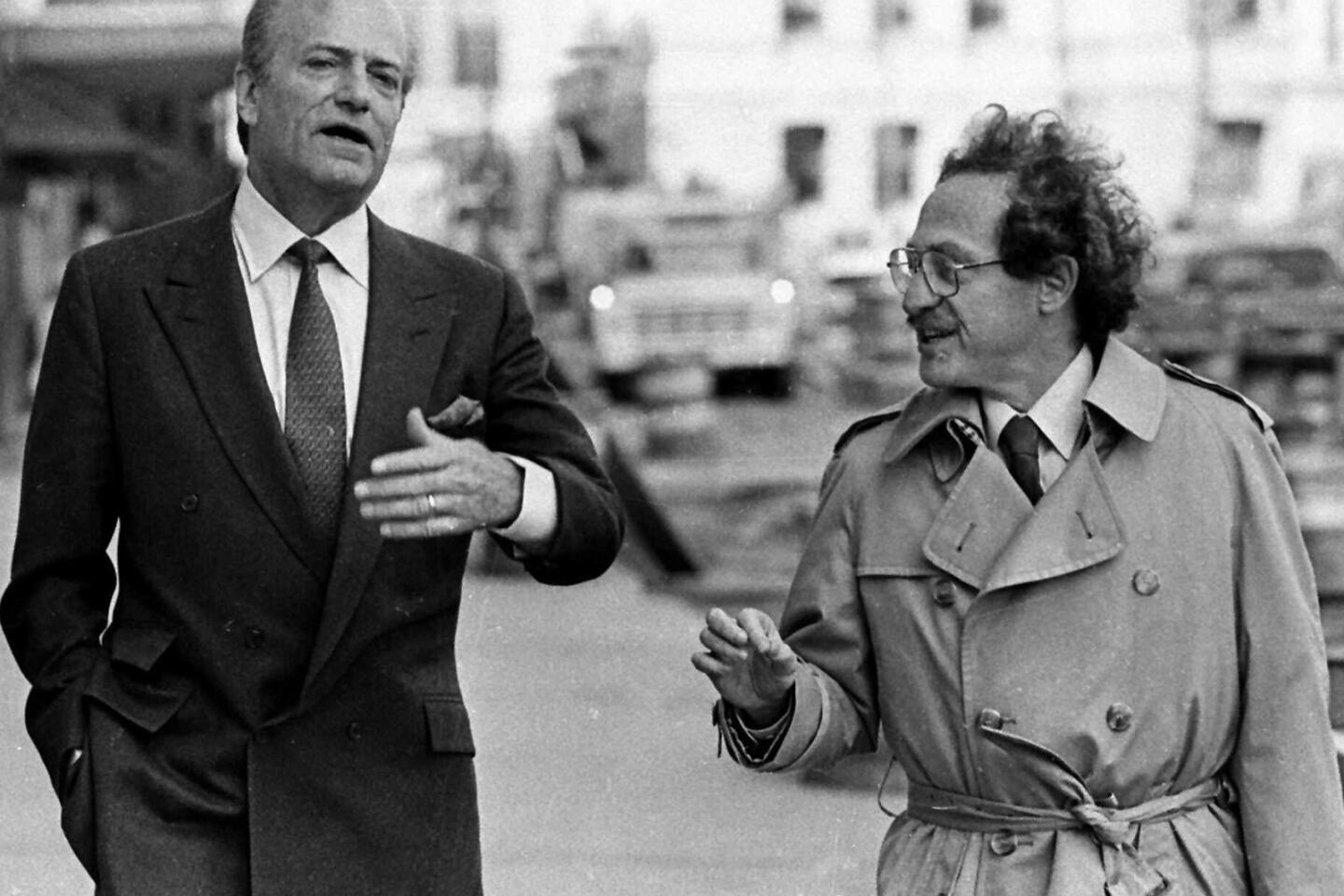

Danish-born socialite Claus von Bulow, left, shown with attorney Alan Dershowitz in April 1985, was convicted in 1982 and then acquitted three years later on two counts of attempting to murder his American heiress wife, Sunny, with injections of insulin. The high-profile case has been called one of the most sensational courtroom dramas in modern U.S. history. He was 92.

(Charles Krupa / AP) 16/33

Herman Wouk explored the moral fallout of World War II in the Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Caine Mutiny” (1951) and other widely read books. Determined to produce a “great war book,” Wouk wrote “The Winds of War” and its sequel, “War and Remembrance,” in the 1970s, and the two sweeping novels became the basis for a pair of television miniseries. He was 103.

(Douglas L Benc Jr / AP) 17/33

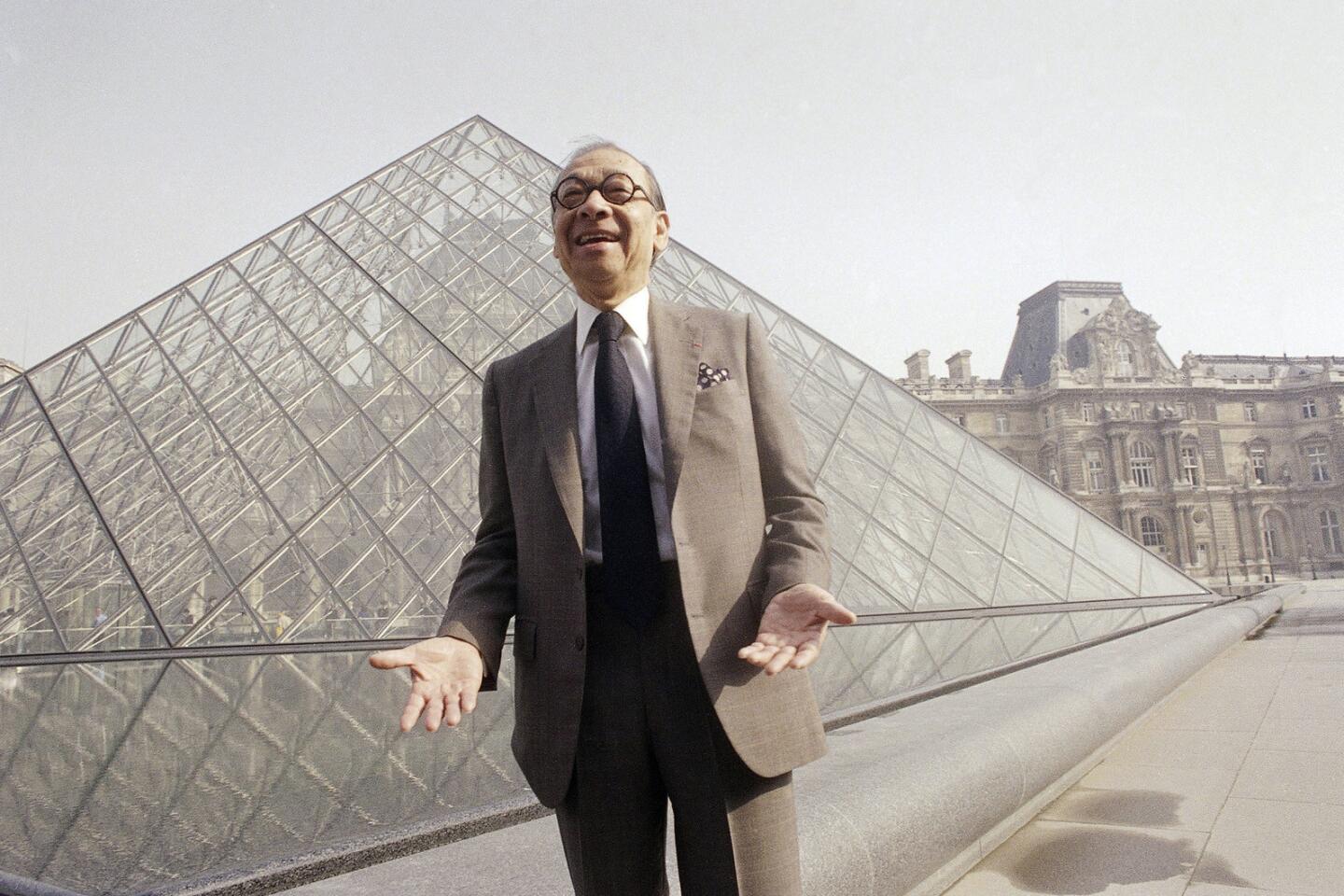

Architect I.M. Pei had a client list that included French President Francois Mitterrand for the Louvre and Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis for the John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library in Boston. Among several Pei projects in the Los Angeles area are the former Creative Artists Agency headquarters in Beverly Hills and the Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. He was 102.

(Pierre Gleizes / AP Photo) 18/33

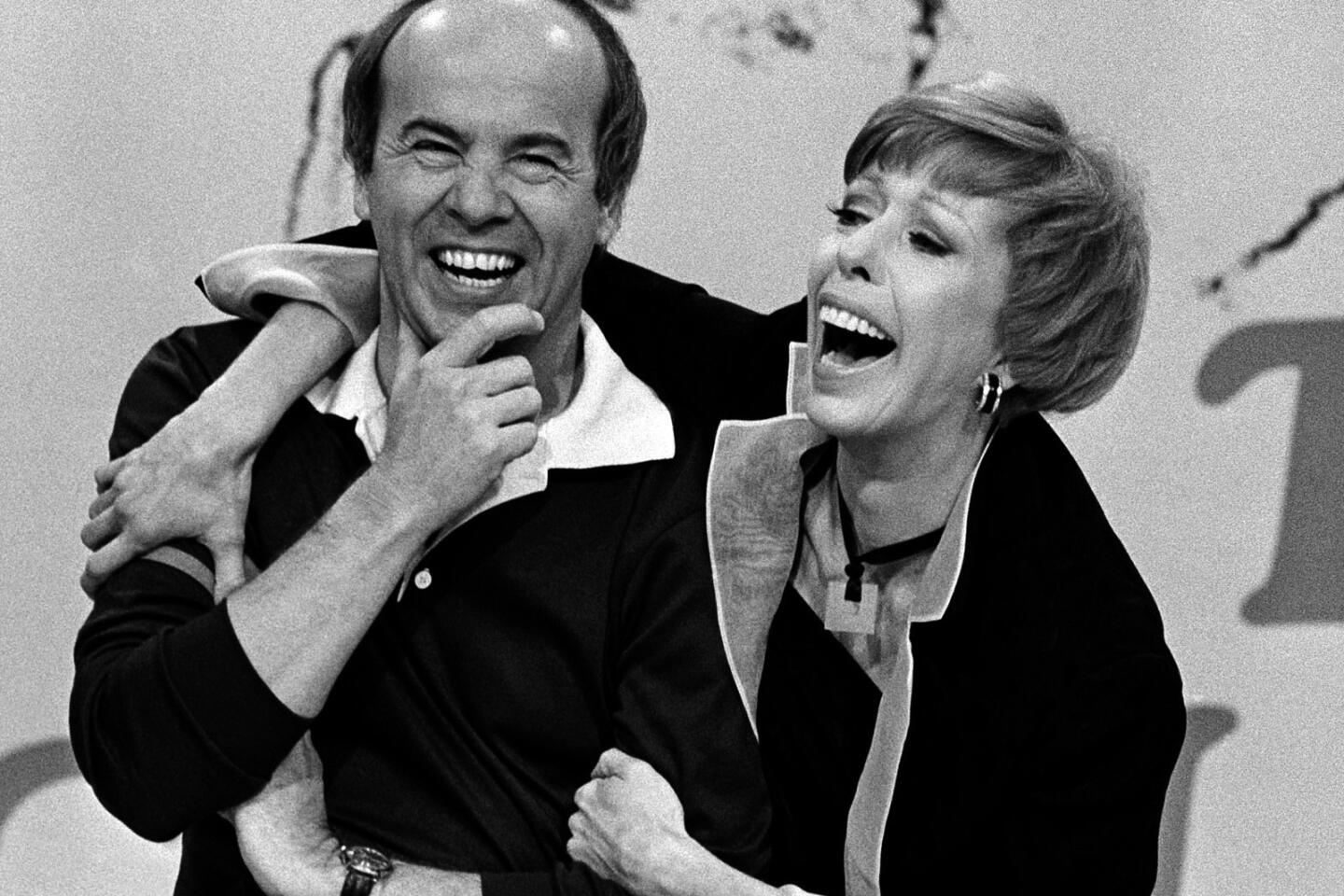

Tim Conway came to prominence on television as a bumbling ensign in “McHale’s Navy” opposite Ernest Borgnine from 1962 to 1966, then became a regular on “The Carol Burnett Show,” where he famously developed a knack for making costar Harvey Korman crack up. He also starred in the “Apple Dumpling Gang” movies in the 1970s and gained fame with a new generation as the voice of Barnacle Boy on “SpongeBob SquarePants.” He was 85.

(George Brich / AP) 19/33

John Singleton’s 1991 debut, “Boyz n the Hood,” was an inner-city coming-of-age story that earned two Oscar nominations and put the young filmmaker in the company of emerging black moviemakers such as Spike Lee and Mario Van Peebles. Singleton went on to direct “Poetic Justice” (1993), “Higher Learning” (1995) and “Baby Boy” (2001), which featured Taraji P. Henson at the start of her career. He was 51.

(Christopher Polk / AFP/Getty Images) 20/33

Grammy-nominated rapper Nipsey Hussle was gunned down outside his Marathon Clothing store in the same South L.A. neighborhood where he was known as much for his civic work as he was for his hip-hop music. He was 33.

(Matt Winkelmeyer / Getty Images for Warner Music) 21/33

Sidney Sheinberg, right, with Steven Spielberg and Lea Adler, Spielberg’s mother, at a 1994 Beverly Hilton gala.

(Shepler, Lori / Los Angeles Times) 22/33

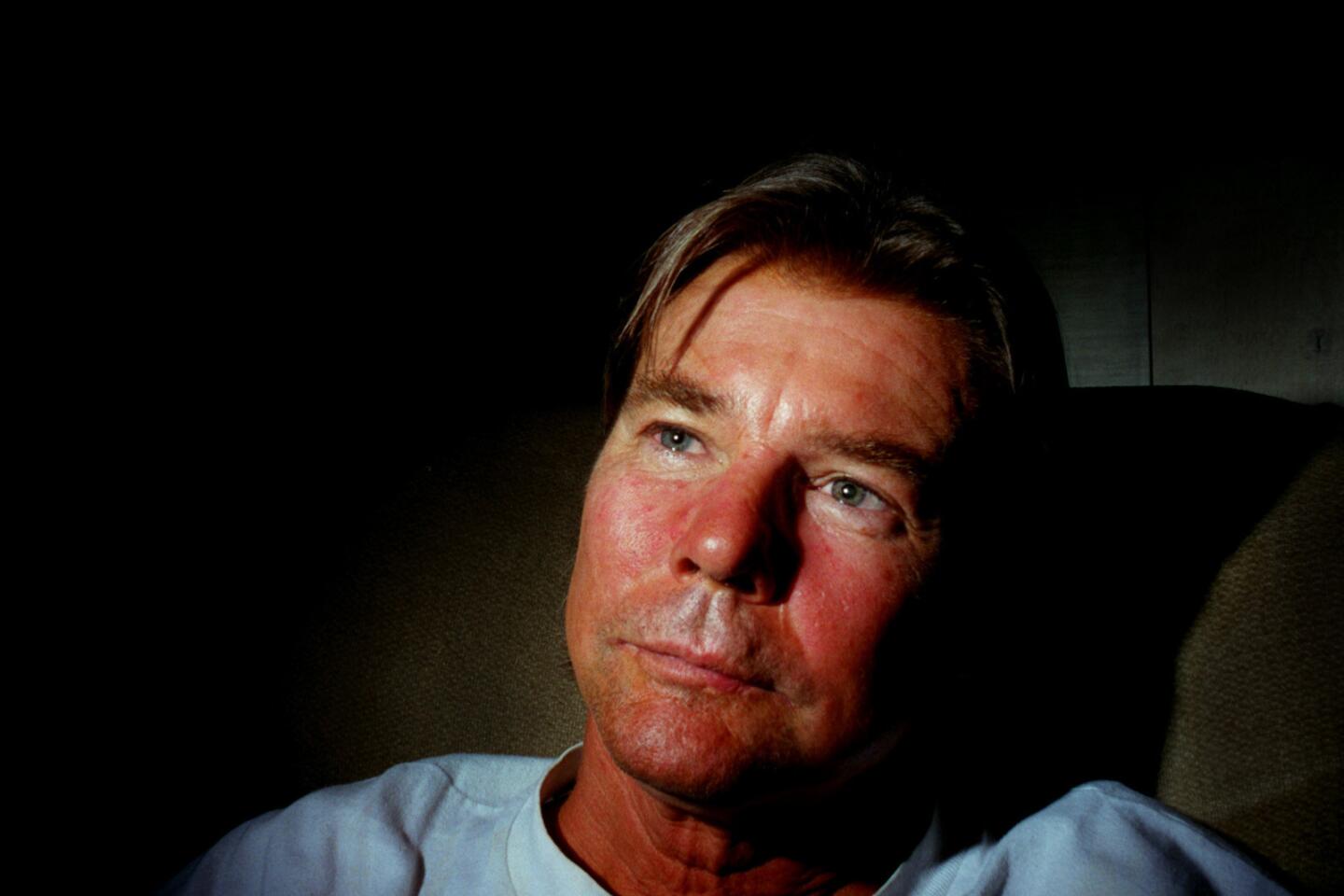

Jan-Michael Vincent was a golden boy of 1970s Hollywood action films and went on to star in the mid-1980s TV adventure series “Airwolf.” But his erratic behavior and cocaine consumption was a major reason “Airwolf” was canceled. He was 74 by most accounts, but the death certificate listed him as 73.

(Alex Garcia / Los Angeles Times) 23/33

Sitcom star Katherine Helmond had memorable roles as ditzy matriarchs in “Soap,” “Who’s the Boss?” and “Coach.” Her work as Jessica Tate on the 1970s parody “Soap” earned her seven Emmy nominations, and she was nominated again in 2002 for her guest role in “Everybody Loves Raymond.” Helmond also starred in director Terry Gilliam’s films “Brazil” and “Time Bandits.” She was 89.

(Chuck Burton / AP) 24/33

André Previn conquered L.A. with his artistic genius twice: first as an Academy Award winning composer of Hollywood movie music, then as music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. A conductor and pianist who toggled between classical, pop and jazz, Previn won Oscars for “My Fair Lady” (1964), “Irma la Douce” (1963), “Gigi” (1958) and “Porgy and Bess” (1959). He was 89.

(Patrick Downs/ Los Angeles Times) 25/33

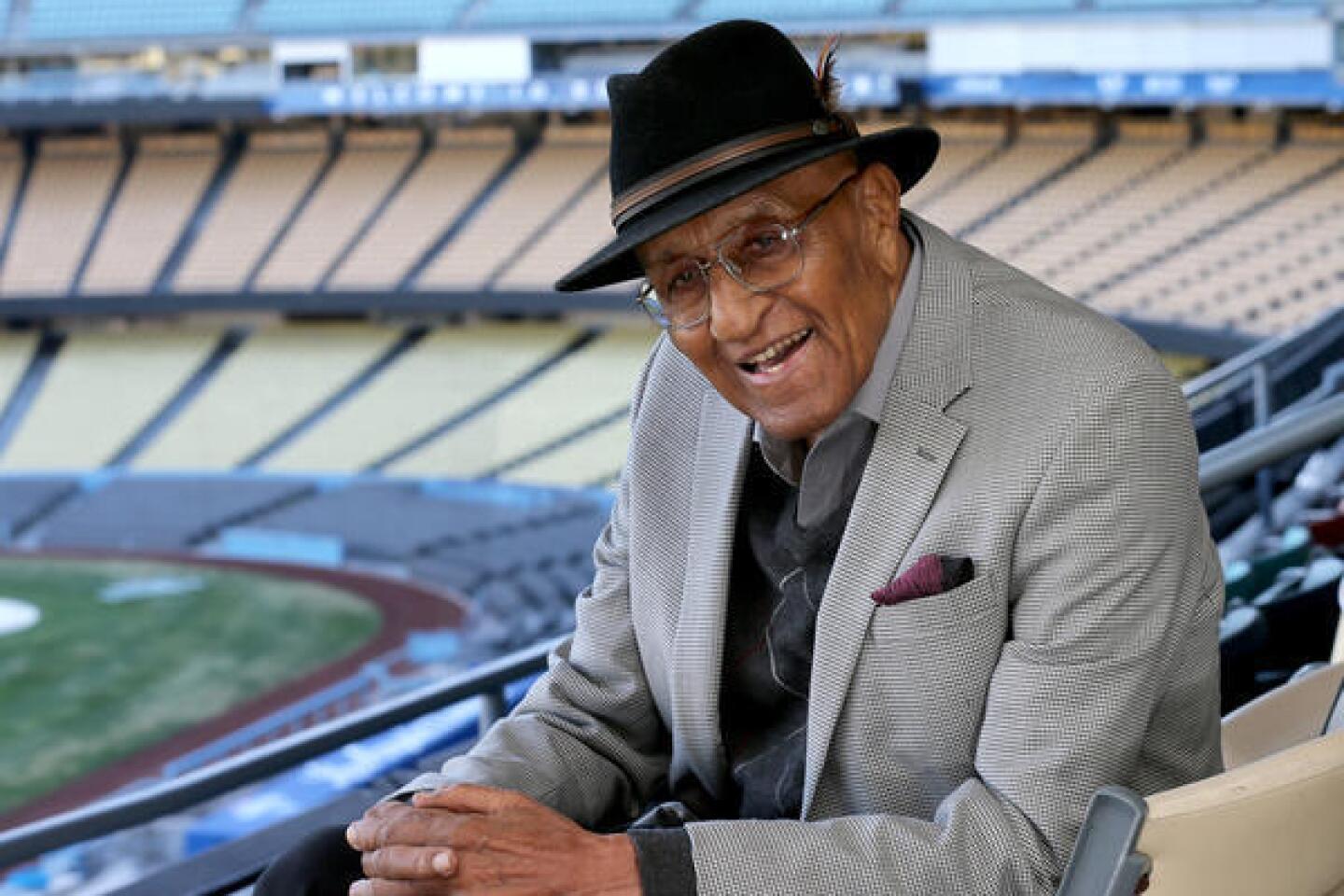

Dodgers right-hander Don Newcombe was the first outstanding African American pitcher in the major leagues and in 1949 became the first to start a World Series game. The 6-foot-4, 240-pound hurler was also the first player in major league history to have won the rookie of the year, Most Valuable Player and Cy Young awards. He was 92.

(Luis Sinco / Los Angeles Times) 26/33

Michigan Democrat John Dingell Jr. used his considerable power in the House of Representatives to uncover government fraud and defend the interests of the automobile industry. Known as “Big John” and “The Truck” for his forceful nature and 6-foot-3-inch frame, Dingell was the longest-serving member of Congress in U.S. history. He was 92.

(Win McNamee / Getty Images) 27/33

Albert Finney starred in films as diverse as “Tom Jones,” “Annie” and “Skyfall.” One of the most versatile actors of his generation, he played an array of roles, including Winston Churchill, Pope John Paul II, a southern American lawyer and an Irish gangster. He was 82.

(Graham Barclay / For The Times) 28/33

Michelle King was the first African American woman to lead Los Angeles Unified School District. Her major accomplishment was pushing the graduation rate to record levels by allowing students to quickly make up credits for failed classes. She was 57.

(Al Seib / Los Angeles Times) 29/33

Grammy-winning singer and songwriter James Ingram topped the charts in the ‘80s with hits like “Baby, Come to Me” and “Somewhere Out There.” He also co-wrote the Michael Jackson hit “P.Y.T. (Pretty Young Thing).” He was 66.

(Stefano Paltera / AP) 30/33

Emmy Award-winning writer Bob Einstein was best known as stuntman Super Dave Osborne, whose feats always went wrong. The comedy veteran got his start writing for 1970s variety shows such as “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” and he later played Larry David’s devout friend Marty Funkhouser on HBO’s “Curb Your Enthusiasm.” He was 76.

(Archive Photos / Getty Images) 31/33

Carol Channing was a Broadway star best known for her enduring portrayal of the title character in the musical “Hello, Dolly!” A winner of three Tony Awards, including one for lifetime achievement, she appeared in the play at least 5,000 times. She was 97.

(Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images / Frederick M. Brown/Getty Images) 32/33

Mary Oliver, one of the country’s most popular poets, focused on spirituality, nature and New England. Her poems won the Pulitzer Prize in 1984 and the National Book Award in 1992. She was 83.

(Josh Reynolds / For the Times) 33/33

Herb Kelleher built Southwest Airlines into the biggest discount carrier and set the standard for budget air travel for more than three decades. He and co-founder Rollin King used a formula of short, no-frills trips that spawned dozens of imitators. He was 87.

(Ed Betz / AP)