Duke Snider dies at 84; Dodger Hall of Famer

Duke Snider, one of the Brooklyn Dodgers’ “Boys of Summer” and among a celebrated trio of New York center fielders in the 1950s, died Sunday. He was 84.

Snider died at Valle Vista Convalescent Hospital in Escondido, the Dodgers announced. No cause was given.

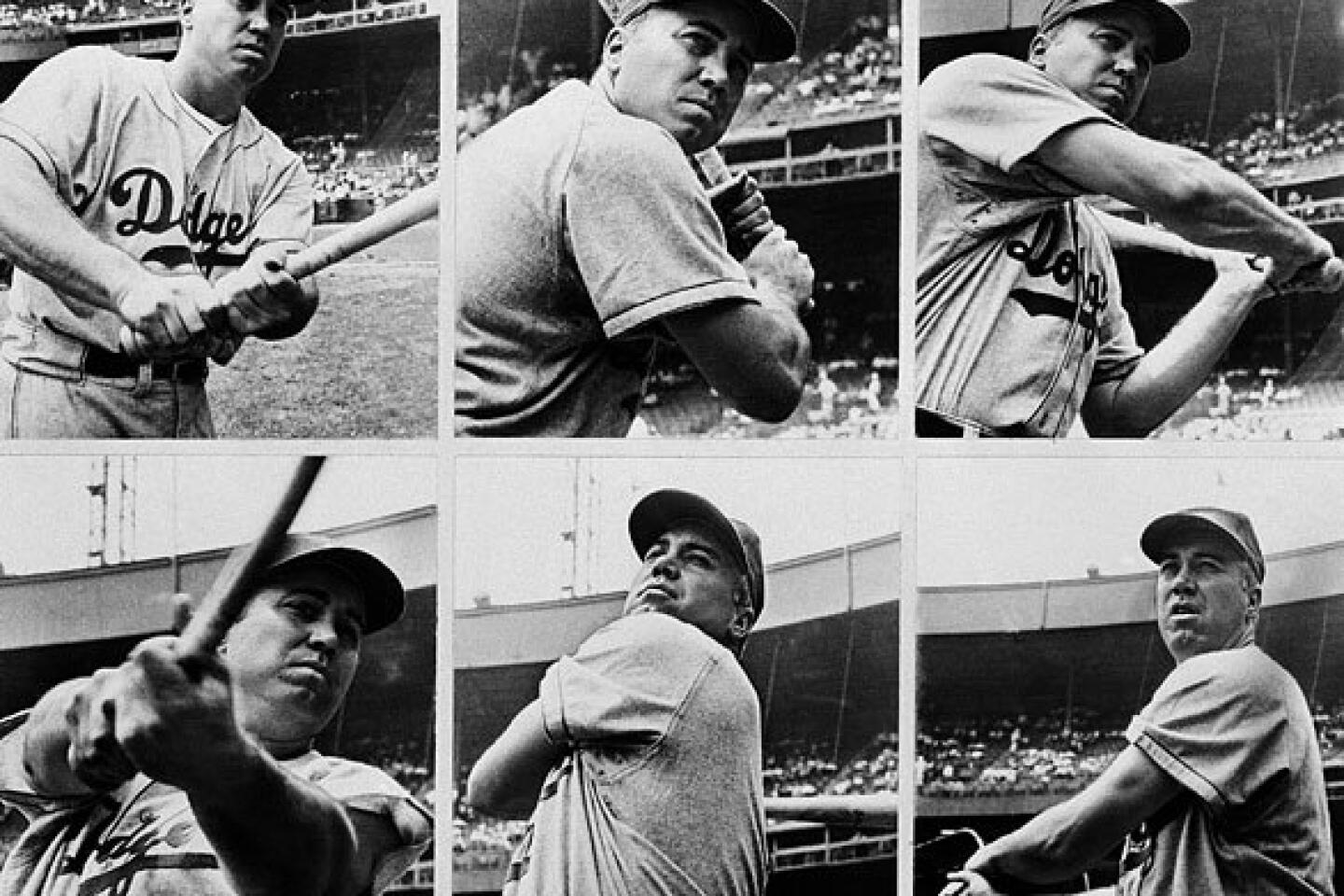

The Duke of Flatbush, a smooth-fielding outfielder and, thanks to his prowess as a home-run hitter, a fan favorite in Ebbets Field, was a Dodger, both in Brooklyn and his native Los Angeles, for 16 of his 18 years in the major leagues. A Hall of Fame member, the eight-time All-Star helped the Dodgers to six National League championships, and Brooklyn’s only World Series title, in his first 11 seasons, providing Dodger power from the left side of the plate.

“He was an extremely gifted talent and his defensive abilities were often overlooked because of playing in a small ballpark, Ebbets Field,” Dodgers’ broadcaster Vin Scully said Sunday in a statement. “When he had a chance to run and move defensively, he had the grace and the abilities of DiMaggio and Mays and of course, he was a World Series hero that will forever be remembered in the borough of Brooklyn. Although it’s ironic to say it, we have lost a giant.”

Snider hit 40 or more homers in five consecutive seasons and during the decade of the ‘50s led all major leaguers in home runs, 326; runs batted in, 1,031; runs scored, 970; and slugging percentage, .569. He finished his career with a lifetime batting average of .295 and 407 home runs, 389 of them as a Dodger, still the team record. He is the only player to have twice hit four homers in the World Series, matching his 1952 feat in ‘55, the year the Dodgers won the Series and he was named major league player of the year by the Sporting News.

He hit the last home run in Ebbets Field and had the first hit in Dodger Stadium, a single on opening day in 1962, and was part of the 1959 Los Angeles Dodgers team that beat the Chicago White Sox in the World Series.

“When you saw him play, the guy could hit, he could run, he could throw, he could field,” former Dodger Manager Tom Lasorda said Sunday. “He was one of the great, great players of our time.”

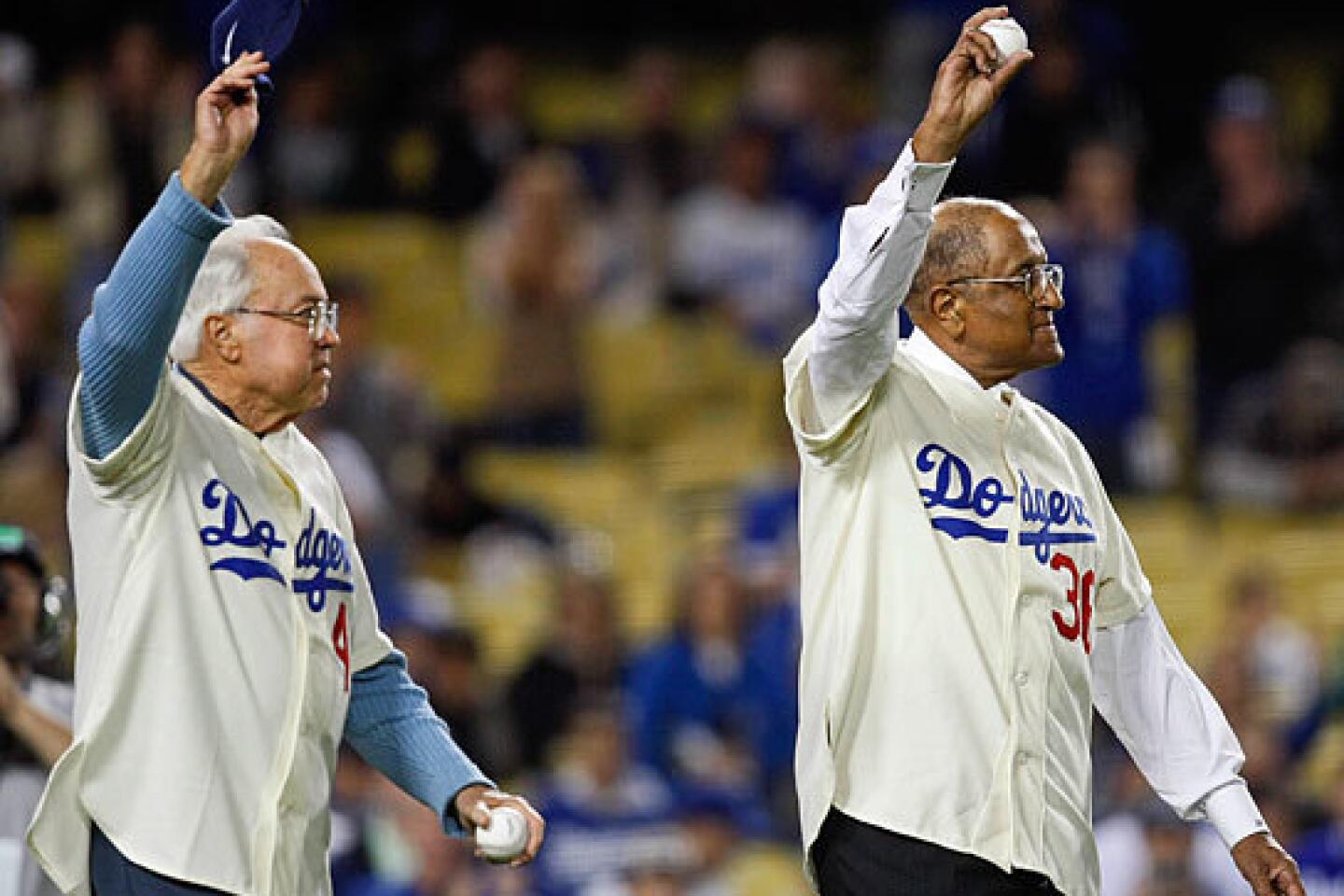

In a simpler but more demanding era — there were only 16 major league teams when he broke in, eight each in the National and American League — Snider was a star among stars, both on his own team and in the Big Apple. Among his Brooklyn teammates were Hall of Famers Pee Wee Reese, Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella. Walter Alston, another Hall of Famer, was the manager, and a couple of young pitchers, Don Drysdale and Sandy Koufax, were showing promise.

And New Yorkers carried on a running argument as to who was the best center fielder in town, Willie Mays of the Giants, Mickey Mantle of the Yankees or Snider. Songwriter-singer Terry Cashman extolled them in his 1981 recording “Willie, Mickey and the Duke,” also known as “Talkin’ Baseball.”

From 1954 through ‘57, when Mays, Mantle and Snider all played full seasons in New York, Snider led the two others in both home runs and RBIs.

“They used to run a box in the New York papers, comparing me and Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays,” Snider recalled for the New York Times in 1980. “It was a great time for baseball.”

Actually, Snider’s entire career was a great time for baseball. He came up as a highly touted prospect in 1947. “His swing is perfect,” Branch Rickey observed upon signing him as a 17-year-old. “And this young man doesn’t run on mere legs. Under him are two steel springs.” He left the game as a player for the ages.

Like Mantle, whose father began grooming him for baseball stardom as a child, Snider had a parental push. Born Sept. 9, 1926, the only child of Ward and Florence Snider, young Edwin Donald Snider grew up in Compton with a bat in his hands. In his book, “The Duke of Flatbush,” written with Bill Gilbert, Snider recalled his father instructing him to bat left-handed, even though he was a natural right-hander. His father pointed out that many ballparks had short right-field fences, that there was a preponderance of right-handed pitchers in the majors and that left-handed batters were two steps closer to first base.

“We argued about the switch loud, long and often because it was awkward,” Snider wrote. “When our backyard arguments reached their loudest, Mom would call out, ‘You two children behave out there.’ ”

Snider also had his father to thank for his nickname. The elder Snider began calling his son Duke as a child, and the kid never objected. “ ‘The Duke of Flatbush’ sounds a lot better than ‘The Edwin of Flatbush,’ ” he often said.

After he graduated from Compton High School, Snider signed with the Dodgers as an amateur free agent. He served in the Navy on a submarine tender in the Pacific from 1944 to 1946.

Snider’s debut with the Dodgers, on April 17, 1947, was especially memorable, but not for anything he did. That also happened to be the day that teammate Robinson got his first base hit, two days after he broke baseball’s longtime color barrier.

“I was in such complete awe of everything going on, I didn’t totally appreciate the significance of the event,” Snider told the San Diego Union-Tribune’s Bill Center in 2004. “I didn’t realize until later … how important it was.”

After two seasons of part-time play — and learning the strike zone — Snider became a Dodger regular in 1949, then blossomed in 1950, hitting .321 with 31 homers and 16 stolen bases. That was also the season that he stamped himself as a center fielder to be reckoned with.

In the ninth inning of the second game of a late-season Sunday doubleheader in Philadelphia, the Phillies’ Willie “Puddin’ Head” Jones approached the plate with the potential tying and winning runs on base, then swatted what seemed to be a home run, a rising line drive.

Snider raced to the base of a wooden fence in Shibe Park, climbed it and, somehow, made the catch.

“I ran over and jumped and my spike caught in the wood,” Snider recalled for the Vero Beach Press Journal in 1999. “I went up and caught it backhanded. I turned my right hand into the wall so the force of me going into the wall wouldn’t knock the ball out of my glove.”

Said teammate Ralph Branca, “The next day I went out [to look at the fence] and his spike marks were, like, 5 1/2 feet high on the wall.”

“I would love to just have a picture of the catch,” Snider told the Los Angeles Times in 2000, but none exists. Televised baseball games, except for the World Series, were a rarity in those early TV days, and the newspaper photographers had already left to process their film.

The “Whiz Kids” Phillies went on to win the National League pennant that year but, coincidentally or not, from the time Snider became a regular, Brooklyn was the team to beat in the NL. The Dodgers won pennants in 1949, ‘52, ’53 — that was “The Boys of Summer” team memorialized by Roger Kahn in his 1971 book of the same name — ’55 and ’56.

It was their misfortune, though, that up in the Bronx, the Yankees were in their heyday. The Yankees beat the Dodgers in the Series each of those years, except ‘55, when Snider hit .320 with four homers and seven RBIs in seven games.

“We didn’t think the Yankees were any better than we were in any of the years that we played them,” Snider told the New York Post in 2005. “We thought we were as good as they were, but they won.”

Snider moved with the Dodgers to Los Angeles in 1958 and spent five more seasons with them — he hit .308 with 23 homers and 88 RBIs for the ’59 World Series title team. But his left knee was bothering him — he eventually needed surgery — and his most productive years were past.

Until Dodger Stadium opened in 1962, the club played at the Coliseum, notorious for its short left-field fence but equally notorious for its vast right field, Snider’s home-run target area. In Ebbets Field, it was 297 feet down the right-field line. In the Coliseum, it was 390, extending to 425 in center.

“There was an awful lot of territory out there,” Snider said. “It just was not fair.”

Snider’s powerful throwing arm served him well in the cavernous Coliseum, however, and prompted teammate Don Zimmer to try to cash in on it. He bet teammates $400 that Snider could throw a ball out of the Coliseum, intending to split the winnings with Snider, who almost made it on his second try.

Instead, though, he heard an ominous “pop” in his elbow, had to miss a game because of the strain and was fined $200 by General Manager Buzzie Bavasi. Having come so close, though, he told Zimmer to hold the money, then on the last day of the 1958 season, did indeed throw a ball from the Coliseum into Exposition Park. Snider collected his $200 from Zimmer. And Bavasi, unaware of the successful try and remorseful about the fine, gave Snider his $200 back.

“So I got $400 out of the deal,” Snider recalled years later.

Snider finished his Dodger career in 1962, then spent a quiet season with the New York Mets and another equally quiet one with the San Francisco Giants.

After his playing days, he managed for 3 1/2 seasons in the minor leagues, then had a second career as a broadcaster for the Montreal Expos before retiring to his home in Fallbrook, where he had an avocado ranch. He was sentenced to two years’ probation, fined $5,000 and was required to pay about $30,000 in back taxes in 1995 after pleading guilty to failure to report income from card and memorabilia shows.

Snider is survived by his wife, Bev — they married in 1947 — sons Kevin and Kurt, daughters Pam Chodola and Dawna Amino, and 10 grandchildren. Services are pending.

Kupper is a former Times staff writer

Times staff writer Dylan Hernandez contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.