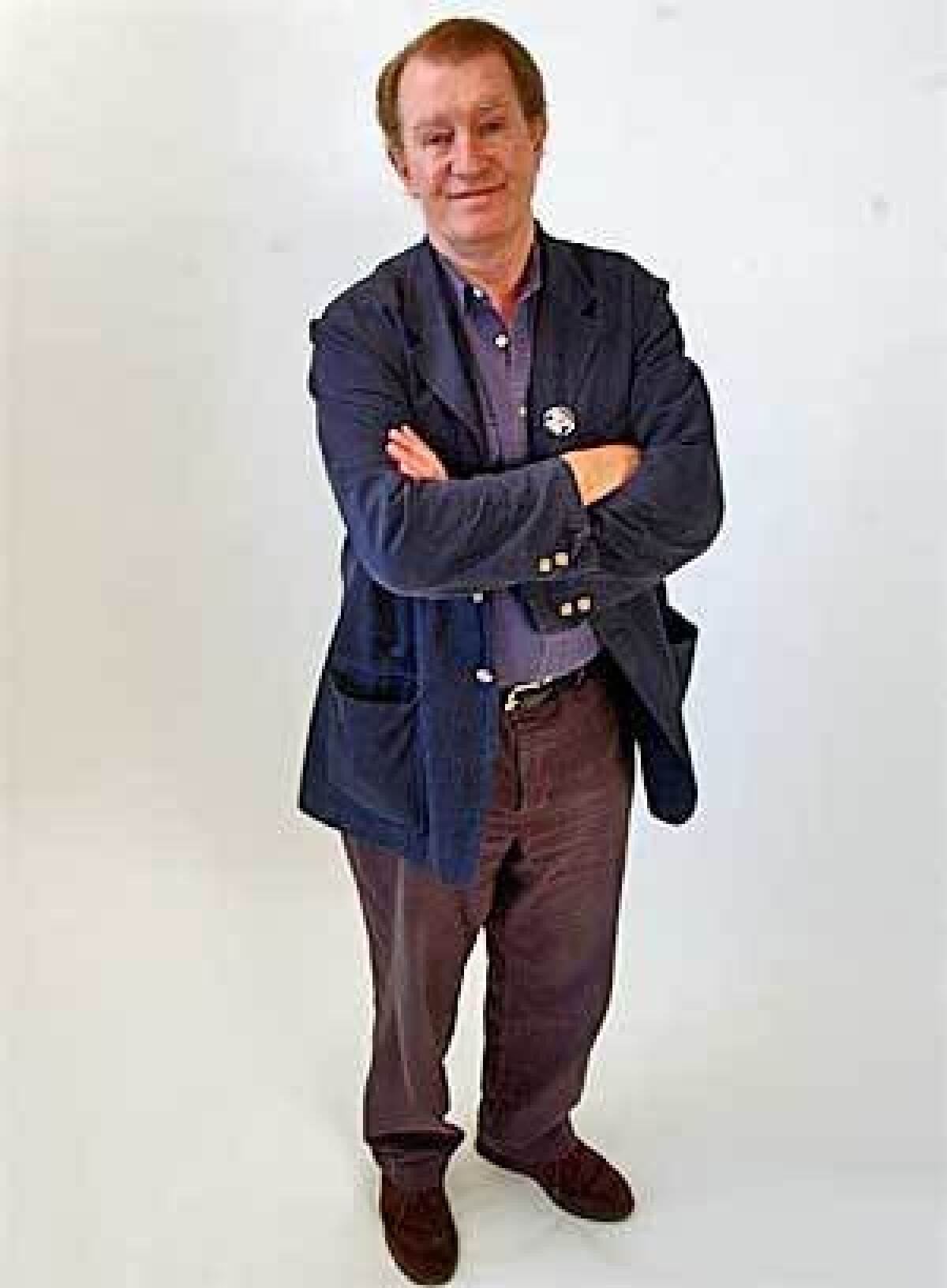

Corin Redgrave dies at 70; actor and activist was part of the famed British family of performers

Actor and political activist Corin Redgrave, a member of the legendary British family of performers that includes his sisters Vanessa and Lynn, has died. He was 70.

Redgrave, who became ill early Sunday, died Tuesday at St. George’s Hospital in London, said a statement on behalf of the family.

“Corin was at the heart of our family and so many friends,” the statement said. “We will miss him so very much.”

Redgrave suffered a heart attack and collapsed at a political rally for the homeless in June 2005. He responded after a period of hospitalization and was released. Four years earlier, he had been treated for prostate cancer.

A familiar stage presence in England, Redgrave appeared in works by Shakespeare, Anton Chekhov, Tennessee Williams, Alan Ayckbourn and others.

He had smaller roles in several dozen movies and television miniseries. He was Hamish, a member of one wedding party, opposite Andie MacDowell in “Four Weddings and a Funeral” (1994). He played Sir Walter Elliot in the 1995 film version of “Persuasion,” based on the novel by Jane Austen; he had a supporting part in the 1993 film “In the Name of the Father”; and, more recently, he played the prime minister in “The Girl in the Cafe” in 2005.

In miniseries he was often cast as a powerful, sinister character. He was Old Jolyon Forsyte, the patriarch of a proud and wealthy family in “The Forsyte Saga” (2002). He played Dr. Kidson, a man involved in a dark family secret in “The Woman in White” (1997), based on the Victorian mystery by Wilkie Collins.

He wrote and performed several one-man plays, as well as a warm and admiring memoir, “Michael Redgrave, My Father” (1995). Michael Redgrave was one of England’s most highly regarded actors from the 1940s until his death in 1985. He appeared in many leading roles with the Old Vic theater company and other stage troupes and in films, including the 1956 film version of George Orwell’s “1984” and an Oscar-nominated turn in “Mourning Becomes Electra” (1947).

Corin Redgrave was praised for “the humanity, compassion and intelligence that he shows as a writer, not least when writing about his father,” in the Financial Times in 2004.

On several occasions he worked with other family members, particularly his older sister, Vanessa. They founded the Moving Theater Company in 1993 to bring politically relevant plays to the stage. One of their most prominent projects was the 1998 London premiere of “Not About Nightingales,” an overlooked Tennessee Williams play about rebellious inmates and vindictive prison guards, for which he won a Laurence Olivier Award.

An earlier project by the Moving Theater Company, “Collateral Damage,” was devoted to antiwar poetry, prose and music. It opened at the National Theatre in London in the early 1990s.

“If artists, actors, musicians and writers just felt they ought to be celebrities and shut up, then the world would be a pretty awful place,” Redgrave said of his constant linking of art and politics in a 2004 interview with The Times.

Born in London on July 16, 1939, he was the middle child of a historic acting family. His mother, Rachel Kempson, was a highly admired stage and film actress, if not as prolific as her husband. Redgrave’s younger sister, Lynn, was as well known as his older sister, Vanessa.

Redgrave’s father was proud of his children’s budding talents but rarely let them know it. As a teenager Corin was told that he was “very good but his eyes are too close together.”

Redgrave’s political activism also followed a family tradition led by his father, who was an outspoken Socialist. From the early 1970s, as his acting career was taking off, Corin Redgrave was open about his Marxist politics and his support of the laboring class. With Vanessa, Redgrave founded the Workers Revolutionary Party in the 1970s to fight efforts to privatize public services, along with other issues.

Through the 1970s and ‘80s his political activities cost him acting jobs, particularly with the BBC, he later said in interviews. He said his father also lost roles because of his politics in the 1950s.

In a 1999 interview with the New York Times, he remarked about his hiring in 1994 for a BBC production of Shakespeare’s “Measure for Measure”: “How strange, here I am again. I was last here in 1970.”

For those 24 years, he said, he worked in only one play a year, most often at London’s Young Vic. “Even there the theater got a little bit of a backlash for employing people like me,” Redgrave said.

In 2004, after the Workers Revolutionary Party had splintered, the Redgraves launched the Peace and Progress party. The platform called for British withdrawal of troops from Iraq and the canceling of debts owed by the world’s poorest countries. It also demanded the return of all British subjects held as terrorism suspects at the U.S. naval base at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

By then, Corin Redgrave’s politics were a better fit with a wider sector and did not seem to interfere with his acting career.

Redgrave began acting after he graduated with honors from Cambridge University. He made his stage debut as Lysander, one of the young lovers in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” at the Royal Court Theatre in London in 1962. Among his earliest movie roles was William Roper, the hotheaded son-in-law in “A Man for All Seasons” (1966).

He married fashion model Deirdre Hamilton-Hill in 1962. They had two children, Jemma and Luke, before they divorced in 1980. She wrote about their marriage in “To Be a Redgrave, Surviving Among the Glamour” with Danae Brook in 1982.

“They always seemed loving, kind, friendly . . . yet it was like a mirage,” she wrote about her former in-laws.

Redgrave married actress Kika Markham in 1985. They had two children, Harvey and Arden.

When his father died, Redgrave’s acting career took a sharp incline. Some people, including his sister Lynn, saw a connection.

“Now there’s a power in knowing that what Corin does on stage is his own thing,” she said in a 1999 New York Times interview.

He was a successful actor in a family filled with them. His daughter Jemma and nieces Joely and Natasha Richardson were also in the business. (Natasha, Vanessa’s daughter, died after a skiing accident in 2009.) Genetics had nothing to do with it, he said.

“We’ve had a great advantage in being able to absorb acting and to see how at its best it’s a delightful life,” he told the Independent of London in 1997.

In addition to his sisters, Redgrave is survived by his wife, children and grandchildren.

Rourke is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.