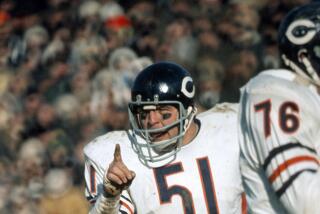

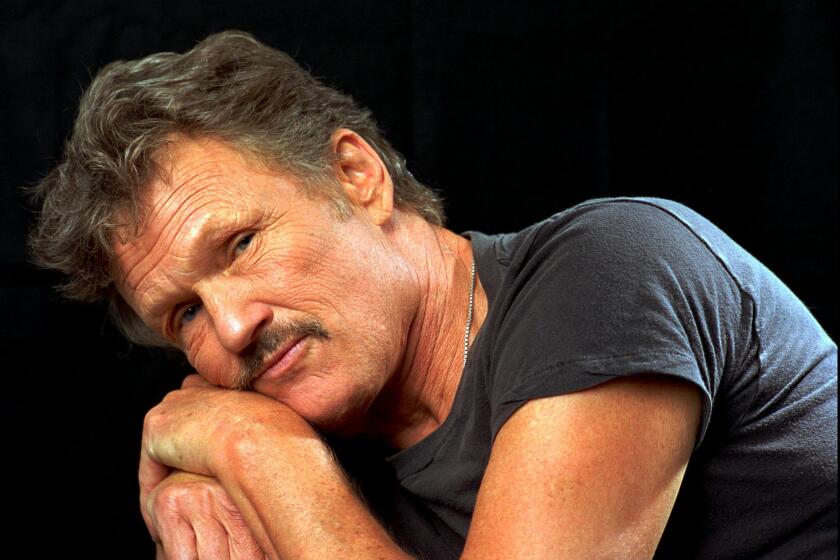

Chuck Bednarik dies at 89; NFL Hall of Famer was rugged two-way player

Football Hall of Famer Chuck Bednarik, one of the last of the leading two-way NFL players who spent nearly entire games on the field, died Saturday. He was 89.

The Philadelphia Eagles, the team he played for from 1949 to 1962, said in a statement that Bednarik died at an assisted living facility in Richland, Pa., after a brief illness.

But his daughter, Charlene Thomas, took issue with the statement, saying Bednarik had long suffered from dementia that she blamed on his playing years.

“He died from dementia from football-related head injuries,” Thomas told the Express-Times of Easton, Pa., on Saturday. “It was not brief.”

Another daughter, Pamela McWilliams, who told the Easton paper that Bednarik had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, acknowledged that dementia is not uncommon at her father’s age, but she said she thought football had a role in it. “They certainly didn’t have the safety equipment they have now back then,” she told the paper.

Known as “Concrete Charlie,” Bednarik epitomized the tough-guy linebacker and also was an outstanding center for the Eagles. He is best remembered for a game-saving tackle at the nine-yard line on the final play of the 1960 NFL championship game. He threw Green Bay running back Jim Taylor to the ground and refused to let him up while the final seconds ticked off. The Eagles won, 17-13.

“Everybody reminds me of it, and I’m happy they remind me of it,” Bednarik once said. “I’m proud and delighted to have played in that game.”

Bednarik, who frequently criticized modern athletes — he once said they “suck air after five plays” — missed only three games in his 14-year career.

The tackle on Taylor actually was the second hit that season that drew headlines. Earlier in 1960, he knocked out New York Giants running back Frank Gifford with a blow so hard that Gifford suffered a concussion and didn’t play again until 1962.

A famous photograph captured Bednarik pumping his fist over Gifford’s prone body, though the linebacker insisted he wasn’t gloating. He said he didn’t notice what happened to Gifford after the hit, and saw only that he had fumbled and another Eagle recovered the ball.

Bednarik was the last NFL starter to play regularly on both offense and defense until Deion Sanders did so for Dallas in 1996. But Sanders’ achievement hardly impressed Bednarik.

“The positions I played, every play, I was making contact, not like that … Deion Sanders,” Bednarik said. “He couldn’t tackle my wife. He’s back there dancing instead of hitting.”

Bednarik said he never made more than $27,000 in a season and supplemented his income by selling concrete, thus earning his nickname. He resented the high salaries paid to later football stars, and at one point pawned his championship ring and his Hall of Fame ring.

“I’m not struggling, but I’m not that well off,” Bednarik told the Associated Press in 2005. “I have my wedding ring. I don’t need to wear nothing else.”

He was born on May 1, 1925, in Bethlehem, Pa., to Slovak immigrant parents. At 18 he was drafted into the Army and flew 30 combat missions over Germany as a gunner during World War II. He played for the University of Pennsylvania from 1945 to 1948 and was All-America in his last two season. He graduated with a degree in physical education and was selected first overall in the 1949 NFL draft by the Eagles.

In 1950, he was All-NFL as a center. He was voted All-NFL as a linebacker from 1951 to 1957, and again in 1960.

He was particularly proud to be part of the 1960 Eagles championship team. So much so that in 2005, when the Eagles won the NFC championship and went on to the Super Bowl, Bednarik said he would root for the opposing team, the New England Patriots. “I hope the 1960 team remains the last one to win,” he said.

The Patriots indeed won that game, but Bednarik later apologized to Eagles owner Jeff Lurie for his statements and was a welcomed visitor at training camp and other alumni functions.

“Philadelphia fans grow up expecting toughness, all-out effort and a workmanlike attitude from this team, and so much of that image has its roots in the way Chuck played the game,” Lurie said in a statement released by the team.

The Maxwell Football Club presents an award in Bednarik’s honor to the defensive player of the year in college football.

In addition to his daughters Thomas and McWilliams, Bednarik is survived by his wife, Emma; daughters Donna Davis, Carol Safarowic and Jackie Chelius; 10 grandchildren; and a great-grandchild.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.