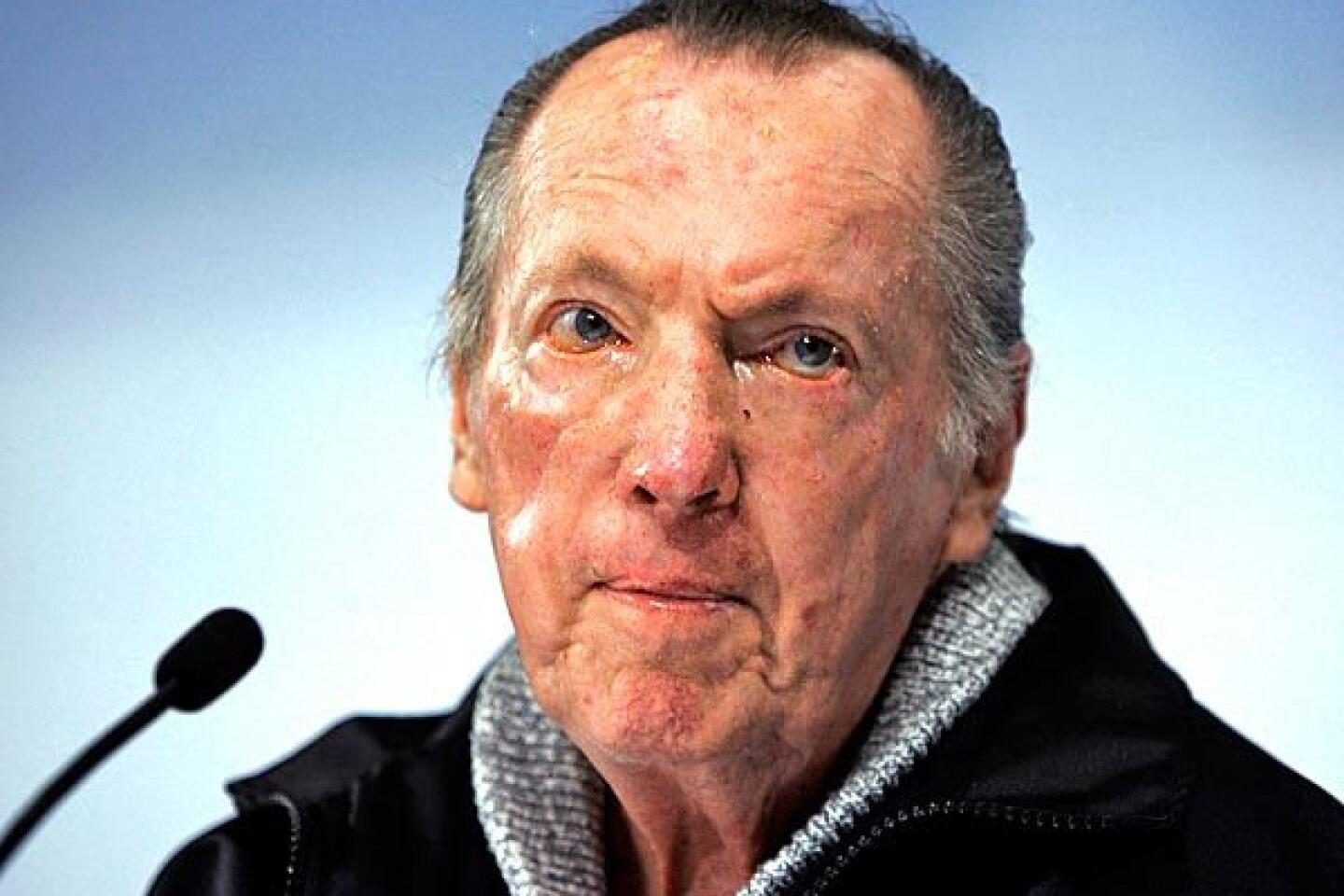

Al Davis dies at 82; Oakland Raiders owner transformed team

Al Davis, the tough-minded owner of the Oakland Raiders who transformed a failing team into a three-time Super Bowl champion and one of the most successful franchises in professional football only to preside over its dramatic decline in recent years, died Saturday. He was 82.

On their website, the Raiders confirmed the death of Davis, whose “Just win, baby!” motto underscored his desire to emerge victorious in every battle, whether it was on the field or in the courtroom.

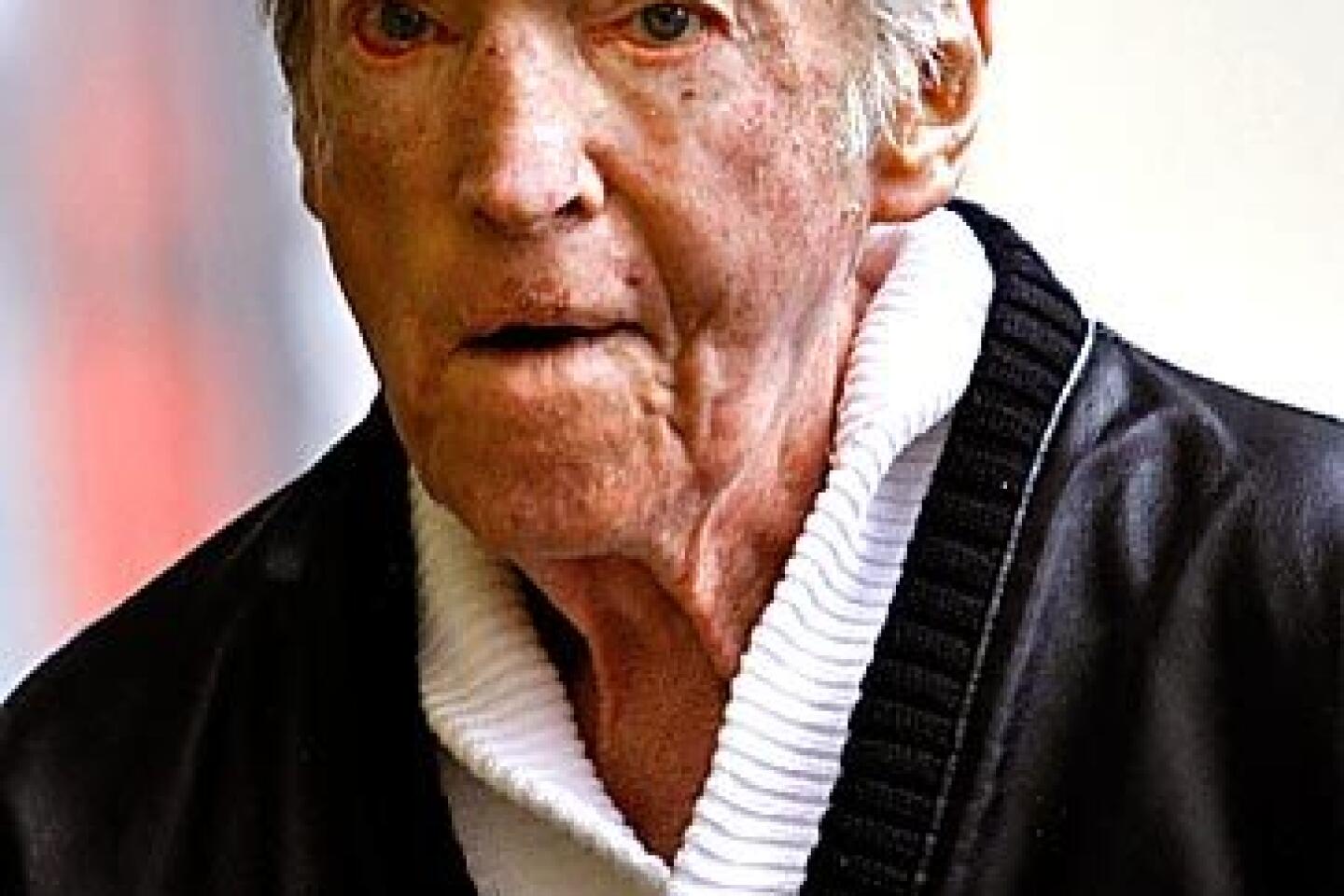

He had been ailing in recent years and did not travel to a Raiders game in Buffalo last month, only the second game he had missed since the team returned to Oakland in 1995.

Except for a brief triumphant run, the Raiders have struggled in the 15 years since returning to Oakland, with only three winning seasons during that span. Many observers pointed to Davis as the main reason, saying the game had passed him by.

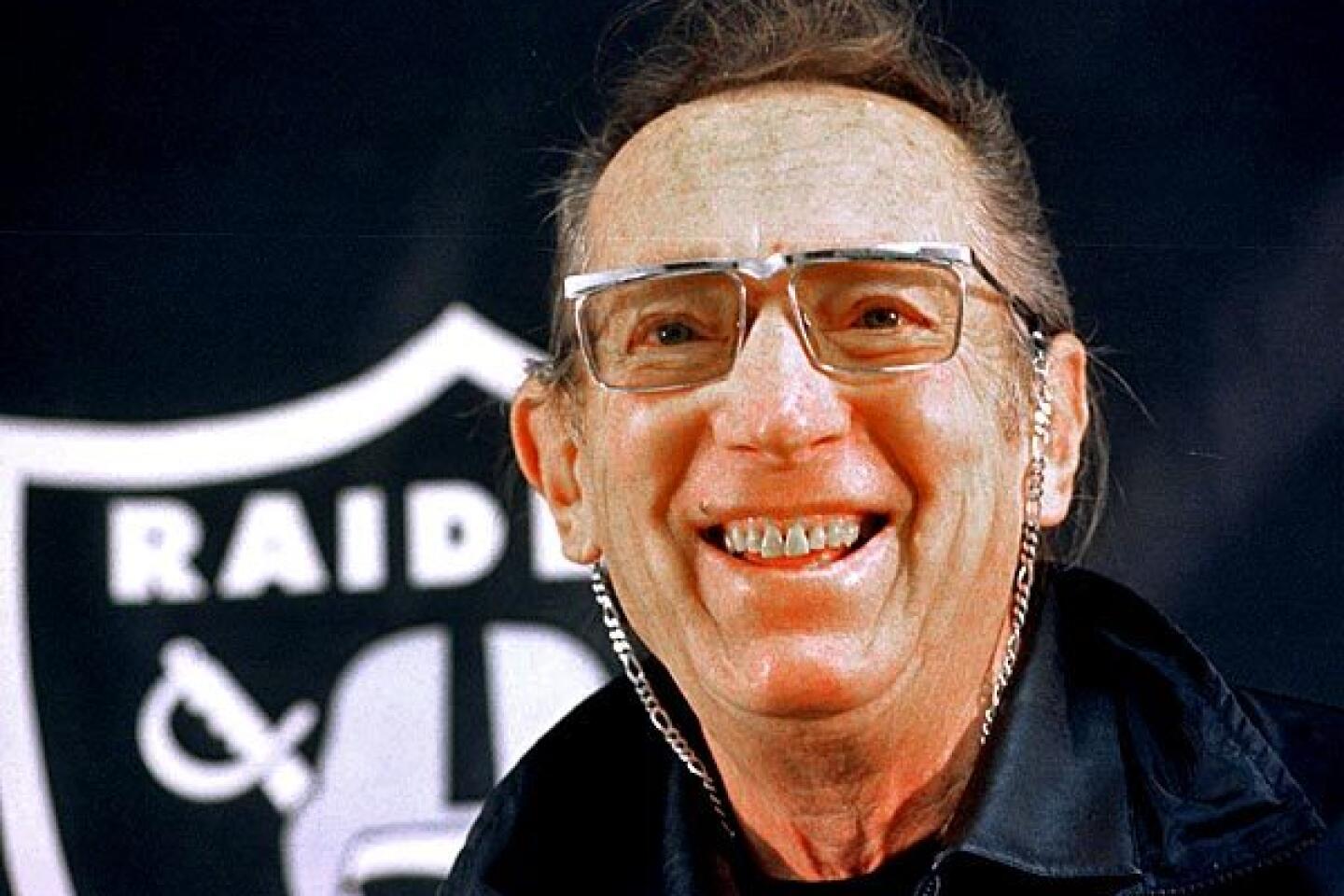

He is perhaps best remembered as the sweat-suit-clad rebel with slicked-back hair and a secretive nature who successfully sued to relocate his team from Oakland to L.A. in 1982, then abruptly moved it back to Oakland 13 years later.

But decades earlier, he briefly served as commissioner of the American Football League and, employing shrewd tactics, helped force an NFL-AFL merger that set the stage for the richest and most influential league in the history of professional sports.

“His contributions and expertise were inspiring at every level — coach, general manager, owner and commissioner,” said Jerry Jones, owner of the Dallas Cowboys and a close friend. “There was no element of the game of professional football for which Al did not enjoy a thorough and complete level of knowledge and passion.”

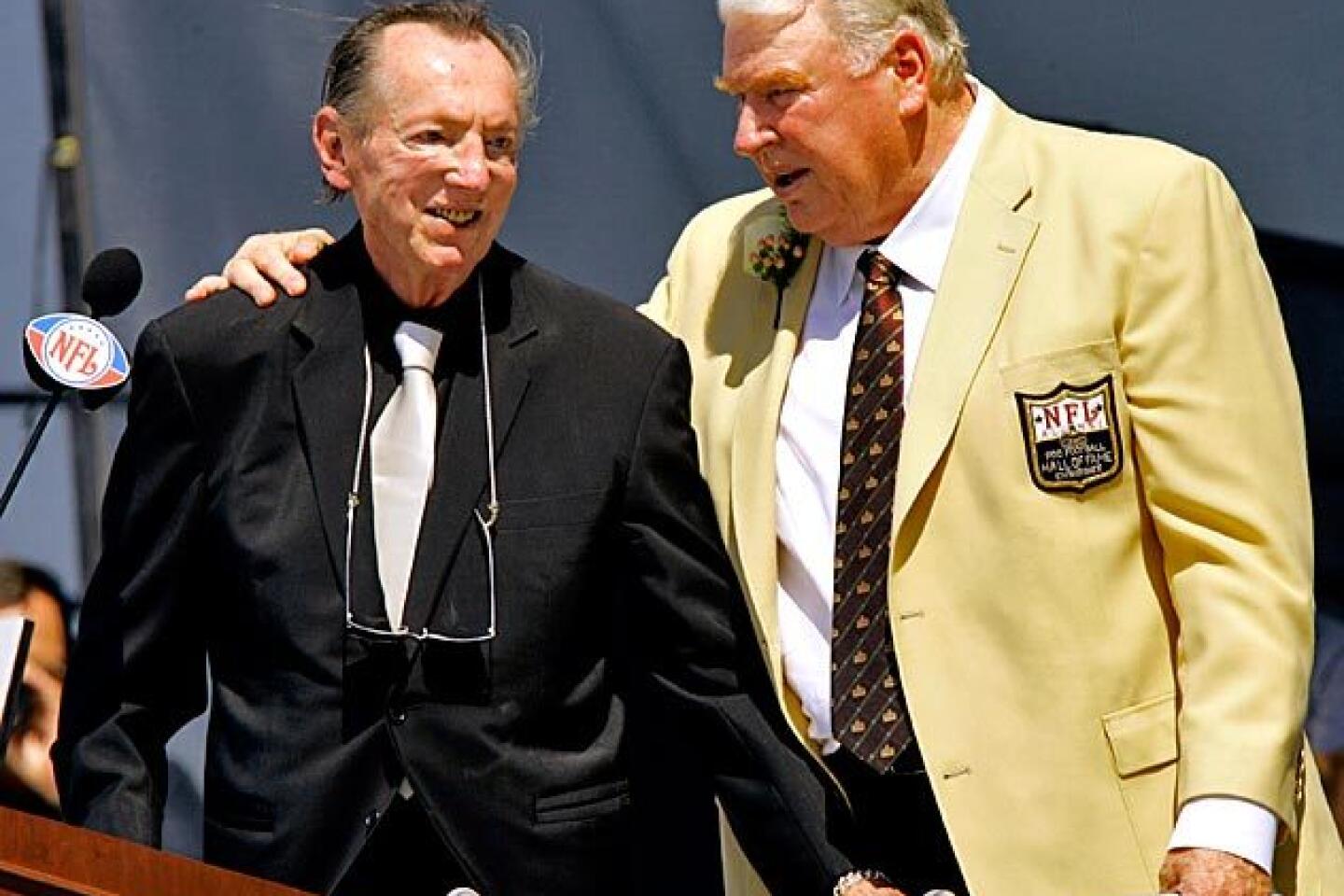

A profound football genius to some, a profane bully to others, Davis loomed large on the NFL landscape for decades and was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1992. No one in professional football history wore so many hats — scout, assistant coach, head coach, general manager, owner and commissioner — or created as much controversy.

“I don’t think there’s anyone in the National Football League — with the possible exception of [former Chicago Bears owner and coach] George Halas — who’s had as big an impact,” said former Raider linebacker Matt Millen. “He influenced a ton of things, either overtly, by pushing for rules, or covertly, by twisting the rules.”

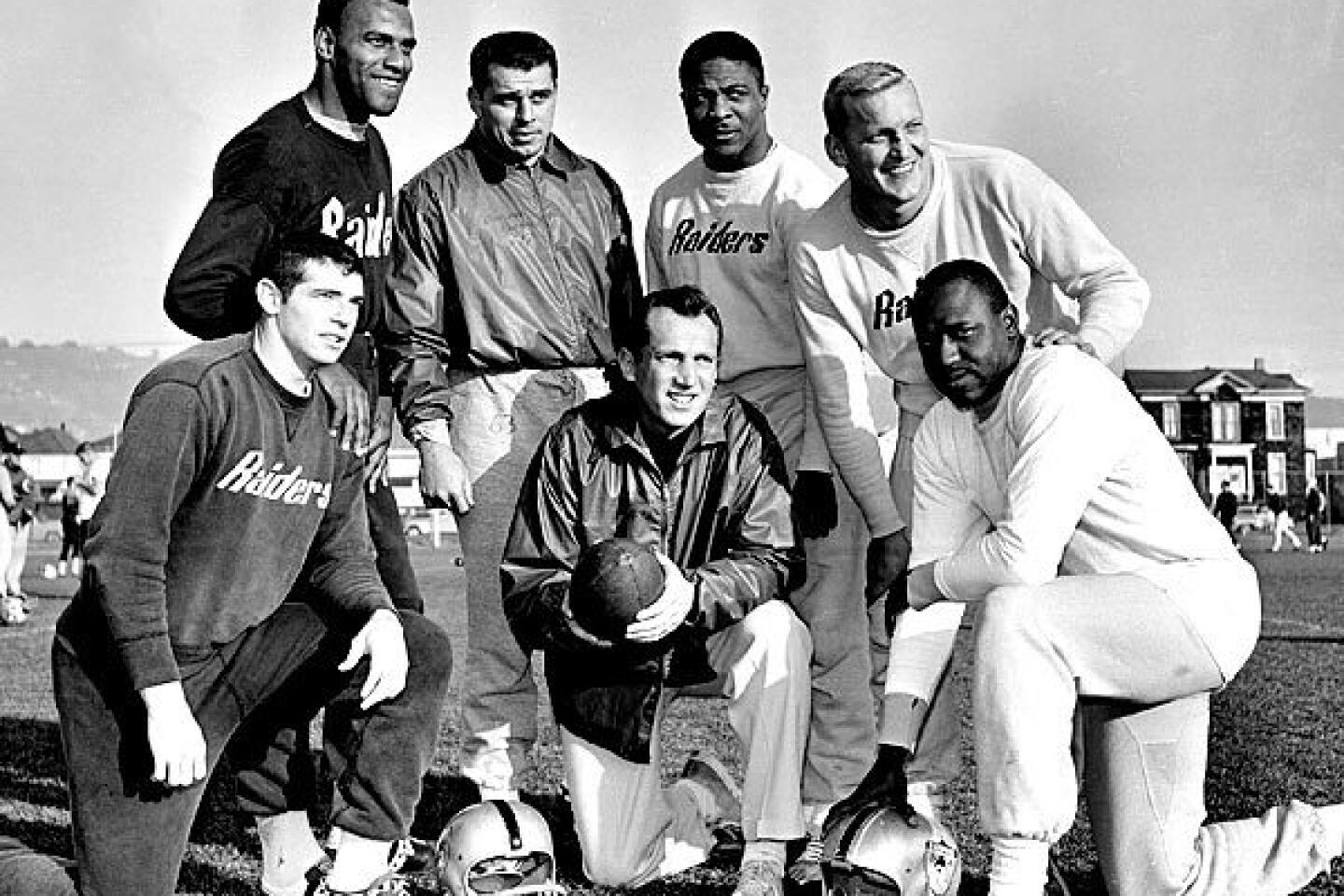

Under Davis, the Raiders developed a reputation as football’s last-chance saloon, a winning franchise built around rejuvenated players who were discarded by other teams that considered them too old, too unruly or otherwise undesirable. It was Davis who introduced the silver-and-black uniforms and pirate logo when — at age 33 — the Raiders hired him in 1963 as head coach and general manager. He also chose the team slogans “Pride and Poise” and later “Commitment to Excellence.”

His impact on the team was immediate and dramatic. The Raiders went from a franchise that had lost 33 of its first 42 games to a 10-4 team that fell one game shy of an AFL division championship. Davis was named AFL coach of the year.

He used the vertical passing game pioneered by his mentor Sid Gillman, the innovative coach who designed the wide-open offensive scheme featuring deep passes to speedy receivers to stretch the field and test the limits of the defense. Davis subscribed to an ultra-aggressive style of defense that included “bump and run” coverage, in which defensive backs would deliver a hard block on receivers at the line of scrimmage before covering them on their downfield patterns.

That take-no-guff approach also typified his style away from the game. A reporter who, like Davis, had grown up in Brooklyn, N.Y., once asked him, “How do you adjust to the laid-back California lifestyle?”

“Adjust?” Davis said, as if sickened by the thought. “You don’t adjust. You dominate.”

He was born in Brockton, Mass., on July 4, 1929, to Rose Kirschenbaum Davis and Louis Davis, who made a small fortune in the garment industry.

Never known for his athletic ability, Davis later said he knew from an early age that he wanted to “build the finest organization in sports.”

At Syracuse University, he earned a degree in English and developed a passion for literature and jazz and a fascination with military history. (For years, typed at the end of every Raider itinerary were the words: “We go to war!”)

Sidestepping the family business, the 21-year-old Davis talked his way into a job as line coach in 1950 at Long Island’s Adelphi College.

Two years later, Davis was drafted into the U.S. Army. For two years, he was head coach of a military football team at Ft. Belvoir, Va., that lost only two games during his tenure. Typically, his actions raised eyebrows. His methods for landing former college and pro players who had been drafted into the military nearly led to a congressional investigation.

Discharged in 1954, Davis got his first job in the pros, as a scout for Weeb Eubank, coach of the Baltimore Colts. A year later, Davis was the line coach and chief recruiter for the Citadel military college in South Carolina, where he spent two seasons.

In 1957 he was hired to coach the offensive line at USC, which was on probation for recruiting violations and slogged through a 1-9 season. Davis persuaded Trojans Coach Don Clark to implement a new blocking scheme that a former player later described as “a kind of hit-’em-and-then-hit-’em-again double block.” Davis and others were credited for turning around the Trojans, who went 8-2 in 1959.

But when Clark retired and Davis was passed over to replace him — a fellow assistant, John McKay, got the job — he headed back to the pros and took over as offensive-end coach for the Los Angeles Chargers, a first-year AFL team. He learned under the tutelage of Gillman, who entrusted him with recruiting players away from the established NFL. That was Davis’ specialty.

Over three seasons — including a relocation to San Diego — Gillman and Davis helped lead the Chargers to the top of the AFL and created a passing offense that gave opposing defenses fits. It was clear that Davis was headed for even bigger things. Gillman said of his young assistant: “There isn’t a doubt in Al Davis’ mind that right now he’s the smartest guy in the game. He isn’t, but he will be pretty damned soon.”

Davis made a splash when he came to the Raiders as head coach in 1963, but he was headed for even greater challenges. In April 1966, Davis took over as commissioner of the fledgling AFL, which was overshadowed by the 47-year-old NFL and its popular commissioner, Pete Rozelle.

With his ability to recruit players, Davis weakened the NFL by luring away disgruntled star quarterbacks. Just eight weeks into the job, he signed quarterbacks John Brodie and Roman Gabriel, and other players. The NFL soon agreed to a merger.

Passed over in favor of Rozelle as the new commissioner of the NFL, Davis returned to the Raiders as managing general partner with a 10% share of the franchise. It reportedly cost him $18,500 — a phenomenal investment considering the latest Forbes magazine rankings had the Raiders valued at $761 million. By the mid-1970s, Davis had acquired full control of the franchise, although he never owned all of it. Many individuals own part of the Raiders, but they always entrusted Davis to run the team.

“The things that people criticize him for were probably also the things they should praise him for,” said Hall of Fame Coach John Madden, whom Davis hired in 1969 to coach the Raiders.

“Al has his own ideas, and many of them are contrarian,” Madden said. “When people said, ‘Let’s do it the way we’ve always done it,’ Al would say, ‘Hey, wait a minute, let’s look at this. Maybe there’s another way.’”

By the end of the 1980 season, the Raiders were two-time Super Bowl champions and one of the NFL’s most popular teams. Despite a decade of sellout seasons in Oakland, however, Davis could not persuade the city to make major improvements to the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum.

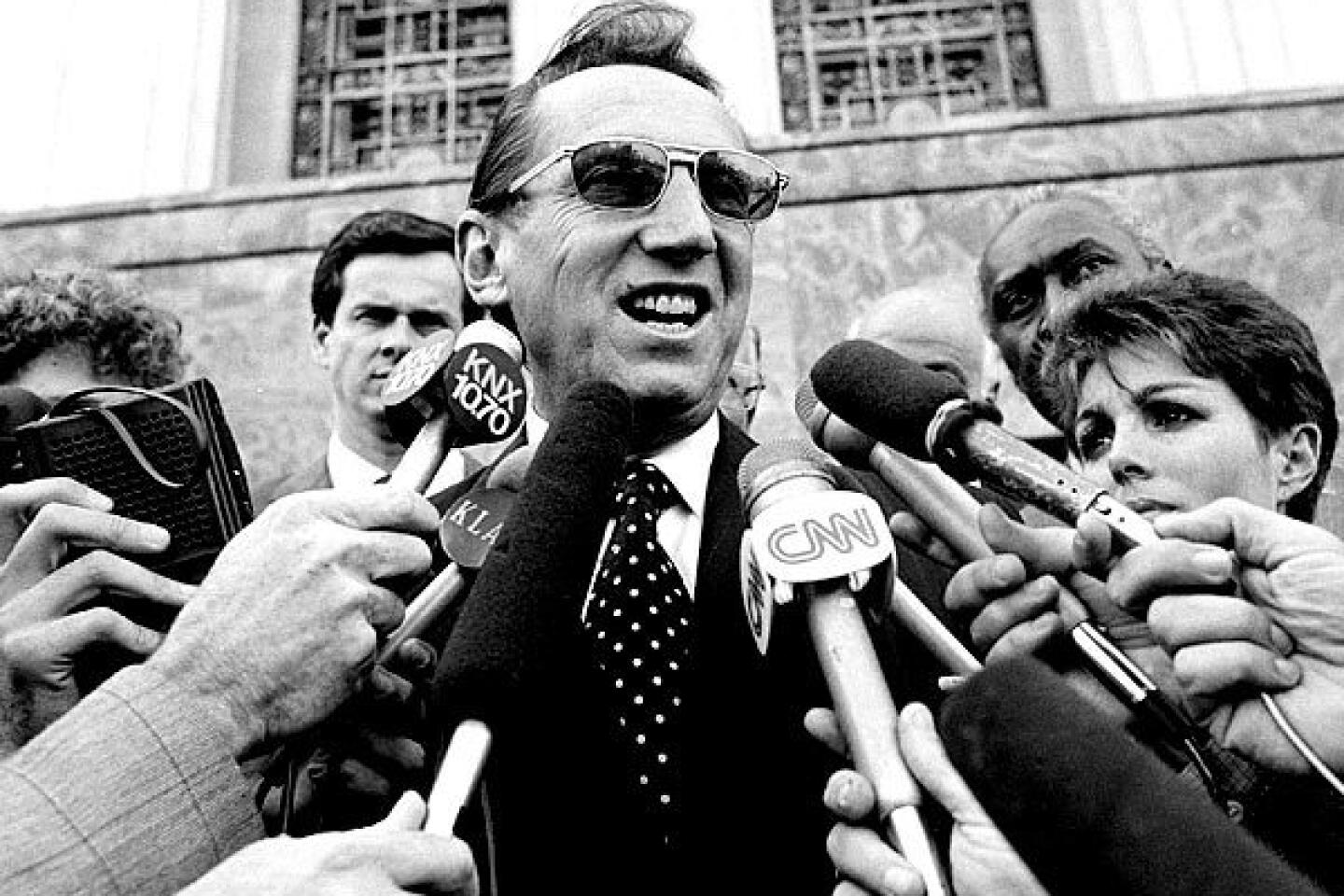

Arguing that his team needed better digs — and the franchise needed the extra revenue to remain competitive — Davis signed an agreement with the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum in March 1980. For a team to relocate, the NFL requires a three-quarters vote from its ownership, so when Davis tried to move to L.A. without that, he was forced by a court injunction back to Oakland.

In 1982, after a lengthy federal court battle, a U.S. District Court jury unanimously ruled for the Raiders and against the NFL on antitrust and bad-faith counts. Two months later, Davis announced he had signed a 10-year deal with five successive three-year renewal options to play at the L.A. Coliseum.

The Raiders played their first game in Los Angeles in August 1982 and the following season won their third Super Bowl. Tens of millions of viewers watched as Rozelle and Davis — bitter adversaries in the courtroom — shook hands in the locker room after the game.

Throughout the 1970s and ‘80s, Davis’ Raiders provided the NFL with some of its most colorful characters, players such as quarterback Ken “The Snake” Stabler, linebacker Ted “The Mad Stork” Hendricks and cornerback Lester Hayes, who would smear his hands and forearms with Stickum before every game.

Davis later said he didn’t realize the extent of his players’ involvement with drugs and alcohol. They included defensive end Lyle Alzado, who admitted to having used human-growth hormone and later died of cancer; defensive back Stacey Toran, who had a high blood-alcohol level when he was killed in a car crash; and defensive end John Matuszak, who died of an overdose of Darvocet, a prescription painkiller. When he became aware of the problems, Davis took steps to deal with the problem, including assigning an assistant coach to monitor off-field activity.

Although the Raiders enjoyed some success in Los Angeles, highlighted by their 38-9 victory over the Washington Redskins in Super Bowl XVIII after the 1983 season, Davis was never satisfied playing at the L.A. Coliseum. The stadium had history, dating to the 1932 Olympics, but it lacked luxury boxes, and the team seldom filled the 92,000-seat venue.

Impatient with the Coliseum Commission’s promised renovations, Davis shopped around for a new stadium site. In 1987 he announced plans to move to Irwindale and got a $10-million advance from the city. The deal ultimately collapsed and the Raiders kept the money.

By 1995 Davis had shifted his sights to Hollywood Park, where a $250-million privately financed stadium was to be built. However, the Raiders balked when the league stipulated that they would have to temporarily share the stadium with another NFL franchise in exchange for the right to host two future Super Bowls. Davis unexpectedly moved the team back to Oakland, saying there were no “adequate and already existing” stadiums in Los Angeles.

The NFL said the Raiders abandoned Los Angeles simply because they thought they had found a better deal in Oakland; Davis claimed the league forced him to retreat to Northern California by interfering with his attempt to secure a modern stadium with luxury boxes and other amenities.

He insisted the Raiders retained the territorial rights to the nation’s second-largest TV market and, if the league tried to place another team in Los Angeles, it would have to buy the rights back from the Raiders.

In 2001, the Raiders lost their $1.2-billion lawsuit against the league, a decision that held. A state appeals court also ruled in 2005 that the Raiders were obligated to share with the league revenue gained from their lease in Oakland.

The Raiders also battled with their new landlords in Northern California, suing the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum over promises that they said went unfulfilled after the team returned in 1995. The Raiders were awarded $34 million in 2003, although the club had sought as much as $833 million. As attendance lagged and television blackouts increased, the team dropped to the NFL’s bottom tier in revenue production.

The team didn’t perform particularly well after moving back to Oakland until Coach Jon Gruden led the Raiders to winning records in 2000 and 2001. The resurgence was short-lived; the young coach bolted for Tampa Bay and his new team clobbered the Raiders, 48-21, in the Super Bowl following the 2002 season.

Over the nine years that followed, the Raiders hired six head coaches. Davis’ vertical passing game came to be viewed as outmoded compared with the West Coast offense, created across the Bay by San Francisco 49ers Coach Bill Walsh.

From 2003 to 2009, the Raiders became the first team in NFL history to lose at least 11 games in seven consecutive seasons.

Davis became more reclusive as the seasons passed, seldom speaking with reporters. In January, he broke nearly 18 months of public silence while introducing his latest coach, Hue Jackson.

“I have made mistakes,” Davis acknowledged. “Yes, there’s no question about it, and you got to have great players. But you also, sometimes, have the players and don’t get it done. … Should I take some of the blame? I certainly do.”

He remained intimately involved with the team, traditionally spending a couple of days a week at practice and pulling aside players to give them tips.

“When you think of Al Davis, he gave his whole life to football,” Madden said. “He’s done nothing else. I always told him, ‘You’ve got to do something.’ He never hunted or fished or played golf. His job, his profession, his free time, everything was football.”

Davis had more than a few personality quirks. He didn’t like shaking hands, saying it made him feel like a Las Vegas greeter. He seldom made a public appearance wearing anything other than a black or white Raiders sweatsuit. And, if his team lost in a particular city, he would switch hotels for the next visit.

He also had an almost eerie ability to predict what was going to happen on the field. Davis often watched away games from the press box alongside close friends and an ever-present bodyguard. When angered by a mistake on the field, he would slam his hand on the table and hiss whispered curses.

When it came to hiring, Davis was colorblind. He was the first NFL owner to hire an African American head coach, Art Shell; the first to hire a Latino head coach, Tom Flores; and the first to promote a woman to chief executive, Amy Trask. His generosity was legendary when it came to helping former players in need, although he routinely did so without fanfare. His philosophy: Once a Raider, always a Raider.

The most notable exception was Marcus Allen, the star Raiders running back whose largely unexplained feud with Davis lasted well over a decade and apparently went unresolved. Allen, a former Heisman Trophy winner from USC who was easily the most popular L.A. Raider, accused Davis of trying to ruin his career by instructing coaches not to play him. He inexplicably spent the better part of four seasons on the bench, inspiring fans to wear “Free Marcus” T-shirts.

“I find the whole rule-by-fear mentality that he used to drive the Raiders really sad,” Allen wrote in his autobiography. “Somewhere along the way, Davis lost track of where the man ends and the myth begins.”

After filing suit against the Raiders and the NFL to win his release, in 1993 Allen joined the Kansas City Chiefs, where he spent five more seasons. He was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2003, 11 years after Davis.

Yet many current and former Raiders both feared and revered the team owner, whom they nearly always referred to as Mr. Davis.

“You might not have thought everything he did was the right thing,” former linebacker Millen said. “But he always believed he was doing right by his Raiders.”

Davis is survived by his wife, Carol, and son, Mark. Davis said in interviews that his wife and son will inherit his share of the team.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.