Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen dies at 65. A creative programmer, he was ‘the idea man’

Paul Allen, the taciturn computer programmer who founded the software behemoth Microsoft with Bill Gates when he was 22 and walked away eight years later with what would become one of the largest fortunes in the history of American capitalism, died Monday in Seattle. He was 65.

The cause was complications of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, according to his investment company, Vulcan Inc. It was a disease that Allen battled in 2009 and which had recently returned.

Allen was an essential part of the launch and early success of Microsoft, which thrived on the combination of Allen’s creative programming genius and Gates’ hard-driving business acumen. Allen went on to become a major investor and philanthropist in his own right, something Gates noted in a statement issued Monday.

“Paul wasn’t content with starting one company. He channeled his intellect and compassion into a second act focused on improving people’s lives and strengthening communities in Seattle and around the world,” Gates said. “He was fond of saying, ‘If it has the potential to do good, then we should do it.’ That’s the kind of person he was. I will miss him tremendously.”

The difference between the two Microsoft founders was that “Gates wanted more than anything to make money; Allen wanted more than anything to be the first to spot a technological idea,” Laura Rich wrote in her biography, “The Accidental Zillionaire: Demystifying Paul Allen.” “It was a partnership made in heaven — and it worked.”

Indeed, as early as 1977, Allen was telling Gates and other friends about his vision of a “wired world.” Writing in a trade magazine at the time, he predicted that the personal computer would become “the kind of thing that people carry with them, a companion that takes notes, does accounting, gives reminders, handles a thousand personal tasks.”

Allen left the company’s day-to-day operations in 1983, against the wishes of Gates, a year after beginning treatments for Hodgkin’s disease, another type of cancer that attacks the lymphatic system. The treatments were successful, but the illness had left him exhausted and also newly imbued with a sense of his own mortality and the need, as he put it, “to reevaluate your priorities.”

Microsoft stock went public in 1986, and by the end of the first trading day, Allen’s shares were worth $134 million. He kept a substantial investment in Microsoft stock throughout his life, and his net worth at the time of his death was $20.3 billion, according to Forbes magazine, which ranked him as the 21st wealthiest person in the world this year.

After leaving Microsoft, Allen decided he wanted to donate to worthwhile causes and to invest in “other people to do exciting, new, creative things,” as he told the Los Angeles Times in 1995. He devoted the rest of his life to spending and putting that vast fortune to work — on an eclectic mix of philanthropic causes and myriad investments that included professional sports teams, space travel and technology.

He also indulged himself with three yachts, including the Octopus, a 414-foot craft with a basketball court, two helicopters and two submarines, according to Power & Motoryacht magazine. His legendary onboard parties drew celebrity-studded crowds.

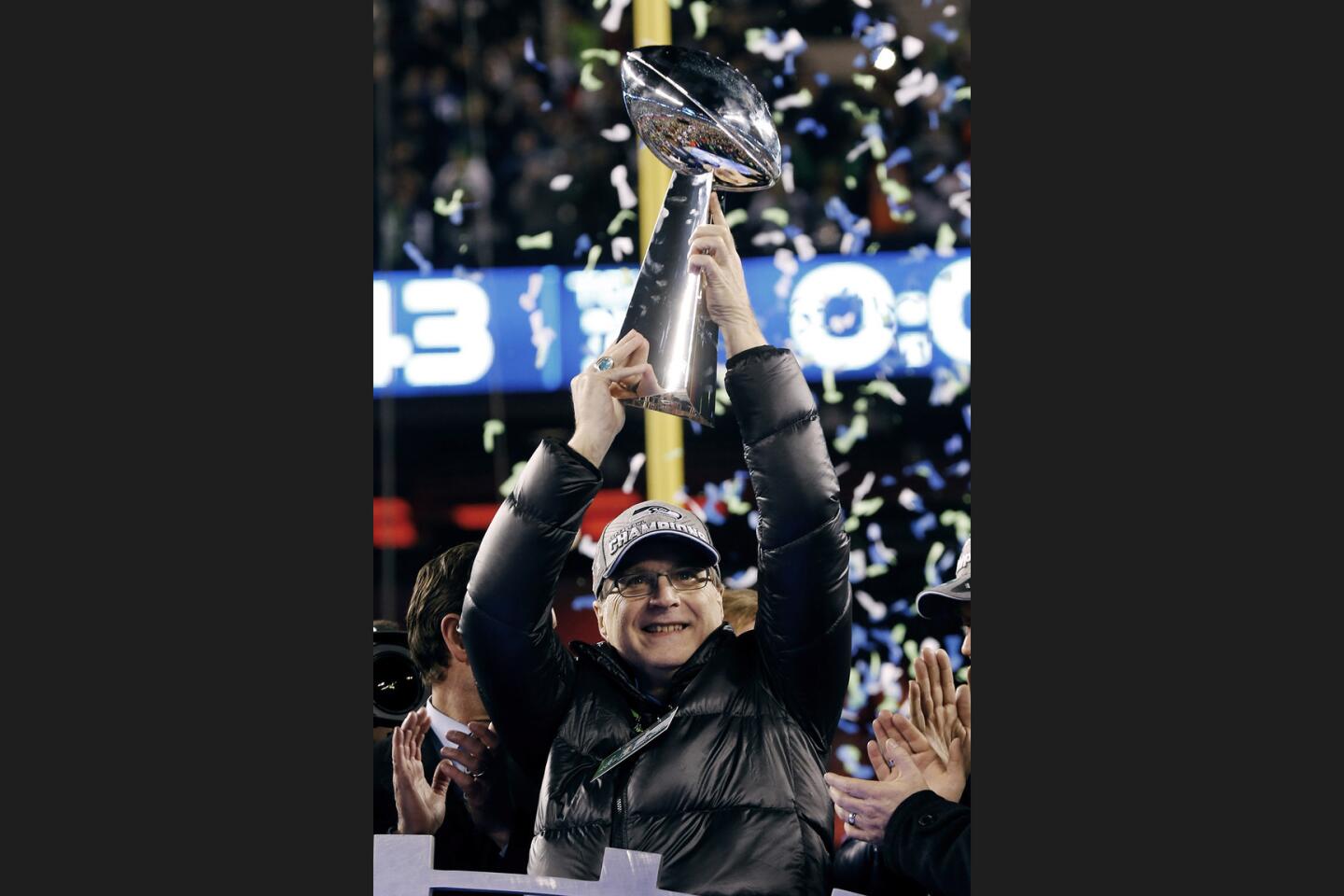

Aside from his association with Microsoft, Allen was probably best known among the general public for owning the NBA’s Portland Trail Blazers and the NFL’s Seattle Seahawks.

His largest venture in Southern California was aerospace company Stratolaunch, founded in 2011 with the goal of launching satellites into orbit from an altitude of 30,000 feet. It built a massive plane with a 385-foot wingspan to do so, but the craft has so far only been tested on the runway at the company’s Mojave Desert facility.

Allen’s other Southern California investments included TrueCar, Activision Blizzard and nuclear fusion start-up Tri Alpha Energy. Allen owned one of the most desirable properties in California, a 120-acre parcel on a hilltop in ritzy Beverly Crest that is on the market for $150 million.

Not all his investments went well. Allen reportedly lost billions of dollars when Charter Communications went through a bankruptcy proceeding in 2009.

Despite his wealth, Allen retained the aura of the computer geek he had always been. He was a preternaturally reserved man who dressed modestly, appeared uneasy in public and shied away from public appearances and interviews. Although he attended most Trail Blazers home games in a courtside seat, personnel at the arena he built were under instructions not to show him on the arena scoreboard.

Over the course of his life, Allen donated more than $2 billion to libraries, museums, AIDS research and even the search for extraterrestrial life, and was an early signatory to the Giving Pledge, committing to contribute a majority of his wealth to philanthropic causes. Much of his philanthropic work was funneled through the Allen Institute, which focused on funding research into brain science, cell science and artificial intelligence.

“Paul’s vision and insight have been an inspiration to me and to many others,” Allan Jones, CEO of the Institute, said in a statement.

Allen was born in Seattle on Jan. 21, 1953. His father, Kenneth, was assistant director of libraries at the University of Washington, and his mother, Faye, earned a certificate to teach elementary school.

Like his parents, Allen was a voracious reader, mostly of novels and science fiction. A neighbor’s record collection turned him on to the rock music scene in the late 1960s and especially Jimi Hendrix, also a Seattle native.

Allen was a sophomore at Lakeside School when he met Gates, who was two years younger, and they quickly bonded over their mutual fascination with the then-emerging world of computers. Lakeside had a computer, a rarity for a high school in that era.

Allen’s and Gates’ first venture together was in 1971, when Allen was enrolled in computer sciences at Washington State University. The two teenagers built a simple computer to analyze city traffic data. The venture never made money, but it convinced them that their time was better spent writing software than building computers.

Gates went to Harvard; Allen dropped out of college and followed him to the Boston area, taking a programming job at Honeywell. On a cold December day in 1974, Allen was on his way to see Gates when he saw a Popular Electronics cover featuring the Altair, a build-it-yourself personal computer kit being sold by two inventors in Albuquerque.

As they later told the story, Allen ran to Gates’ dorm room and persuaded him to help write a version of the programming language Basic for the Altair’s Intel chip, something some experts at the time said couldn’t be done. In a two-month marathon, they did it. On a flight to Albuquerque, where he hoped to sell the program to the Altair’s manufacturer, MITS, Allen realized that a key part of the code was missing. So he wrote it out on scraps of paper on the plane.

It was 1975 and the beginning of Microsoft. Allen went to work for MITS, and Gates stayed at Harvard, both running Microsoft as a part-time venture. By early 1977, the company had developed enough business that Gates dropped out of school and Allen quit MITS to work full time at Microsoft.

In 1980, IBM turned to Microsoft to provide the operating system for its line of personal computers. Microsoft bought an operating system from a smaller Seattle company and upgraded it into MS-DOS. IBM’s computer took off and, with it, Microsoft.

Allen was regarded inside Microsoft as an intuitive thinker who had a sixth sense about new products, according to Stephen Manes’ and Paul Andrews’ 1993 biography of Gates. And Gates was the driven, clear-headed partner who turned Allen’s sometimes random ideas into successful products.

Those differences were evident in the workplace. The two argued frequently, often screaming at each other in front of other employees. But the fights, colleagues said, frequently resulted in good business decisions.

“I guess you would call me the doer and Paul the idea man,” Gates said in 1981. “I’m more aggressive and crazily competitive, the front man running the business day to day, while Paul keeps us out front in research and development.”

Even then, though, Allen seemed to value life outside of work more than Gates did, and he frequently invited co-workers to his house to watch movies and listen to music. He was an accomplished electric guitar player, and his bands performed at his private parties. He even released a blues-rock album titled “Everywhere at Once” in 2013 under the name Paul Allen and the Underthinkers.

When Allen was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s disease and began X-ray treatments in 1983, he began to withdraw from the day-to-day operations. Later that year, he suffered another blow when his father collapsed and died of a blood clot five days after routine knee surgery.

“You realize how precious life is,” Allen told another interviewer. He left Microsoft and spent two years traveling in Europe, pondering what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. All he knew, he said, was that “I wanted to do something groundbreaking.”

Times staff writers Laurence Darmiento, Sam Dean, Lauren Raab and Roger Vincent contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

7:05 p.m.: This article was updated with more information about Allen’s philanthropic work and a comment from Allan Jones, CEO of the Allen Institute.

5:30 p.m.: This article was updated with a statement from Bill Gates.

5 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details of some of Paul Allen’s investments.

3:55 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details of Paul Allen’s life and with comments from Microsoft’s Satya Nadella, Vulcan’s Bill Hilf and Allen’s sister Jody Allen.

3:25 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details.

3:15 p.m.: This article was updated with additional details.

This article was originally published at 3:05 p.m.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.