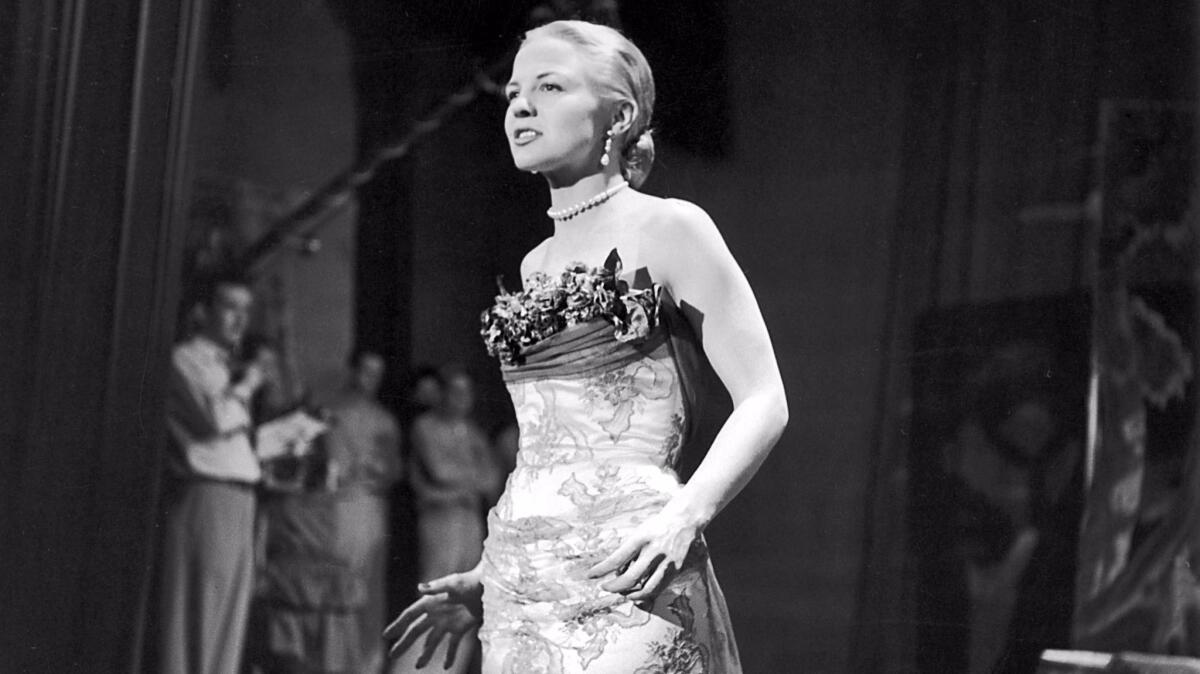

From the Archives: Peggy Lee, Sultry Jazz and Pop Singer, Dies at 81

Peggy Lee, whose soft, rhythmic voice and purring sensuality made her a favorite of jazz and pop audiences for half a century, has died. She was 81.

Lee, who had been in declining health since a stroke three years ago, died of a heart attack Monday night at her home in Bel-Air, said her daughter, Nicki Lee Foster.

She was best known to a broad audience for songs that became her trademark, such as “Fever,” and the Grammy-winning “Is That All There Is?” But Lee also was a gifted songwriter and arranger.

She also was the well-known voice of Peg in the Disney film “Lady and the Tramp” and won a $2.3-million lawsuit against the Walt Disney Co. to recoup royalties from videocassette sales of that movie.

A fine actress, she was nominated for an Academy Award for her role as an alcoholic blues singer in the 1955 film “Pete Kelly’s Blues.”

But it was the voice that captivated generations of audiences.

“If you don’t feel a thrill when Peggy Lee sings, you’re dead, Jack,” jazz critic Leonard Feather said some years ago.

Jazz singer Cleo Laine said Lee “came from a big-band era and knew how to swing. She knew how to sing on the beat when necessary. A lot of people don’t know how to do that. Her simplicity had a lot of nuances that other people just couldn’t grasp, that they just couldn’t imitate to save their lives,” Laine said Tuesday.

Diana Krall, one of the leading singers in jazz today, offered similar praise.

“I love everything about her: her elegance, her wit. And she is one of the greatest influences in what I do as an artist,” Krall said in a statement released Tuesday.

Lee’s work seemed to transcend changing tastes.

“She was never part of any kind of fashion,” said jazz critic Nat Hentoff. “She never engaged in pyrotechnics. She was subtle and enticing in contrast with the belters who show off everything but their musicianship.

“She had some of [Maurice] Chevalier’s ability to connect with the audience to make them think she was singing just to them.”

Born Norma Dolores Egstrom in Jamestown, N.D., Lee was the seventh of eight children. Her mother died when she was 4, and her father, a railway agent, married a woman who by all accounts was physically and emotionally abusive to her stepchildren.

Undaunted by the abuse at home and encouraged by the recognition she received in her school glee club and the church choir, Lee decided to pursue singing. Still a teenager, she found work on a radio station in Fargo, N.D., where the station manager changed Norma’s name to Peggy Lee.

At the age of 17, she left Fargo for Hollywood, arriving with $18 in her pocket. She got small singing gigs, but took jobs as a waitress and worked in a carnival midway.

Discouraged, she returned to the radio job in Fargo and eventually made her way to Chicago, where she got her break.

Lee was singing at the Ambassador West Hotel when Benny Goodman, on the advice of his wife, stopped in to hear her one night.

“I couldn’t believe he was sitting there listening to me,” she recalled years later in an interview with Howard Reich of the Chicago Tribune. “See, I was a big fan of his. . . . So here was Benny Goodman in the room . . . and Benny had a funny way of chewing on his tongue and staring at you at the same time. So when you were performing, you couldn’t really think that he loved it. . . .

“Of course at the time, I didn’t realize that I was really auditioning, that Benny was looking for a replacement for Helen Forrest, who had left the band. . . .

“When I was told that Benny was offering me a job, I thought it was some kind of joke.”

After some initial unpleasantness with Goodman fans who wanted to hear Forrest, the 21-year-old Lee settled into her new job.

“It was like a beautiful dream,” she told Reich. “I would sit there on the bandstand, night after night, just reveling in the music. I could hear the arrangements over and over and never got tired of them.”

Lee’s work with the Goodman band yielded several hits, including “Blues in the Night,” “The Way You Look Tonight,” and “Why Don’t You Do Right.”

Her time with the Goodman band also yielded another benefit: her first husband, Dave Barbour, a guitarist with the band.

After leaving the Goodman band in 1943, she had hits with records such as “That Old Feeling,” and with three songs she composed with Barbour: “It’s a Good Day,” “Don’t Know Enough About You” and “Manana (Is Soon Enough For Me).”

The 1950s were a particularly active time in Lee’s career. She made several popular recordings for Capitol, wrote the title song for the 1954 film “Johnny Guitar,” and wrote songs for other films, including “Tom Thumb.”

“Fever” with its spare jazz arrangement was released in 1958 and helped establish her as an artist who could cross into the pop field.

She had film roles as well, appearing in the 1953 version of “The Jazz Singer” opposite Danny Thomas. She was nominated for an Academy Award for best supporting actress for “Pete Kelly’s Blues.”

“I loved acting.” she later said, “But my agents never brought me another script. I was worth a lot more to them on the road.”

Legal Battle Over Royalties

Her most memorable role of that period came in her off-screen work on Walt Disney’s “Lady and the Tramp.” With Sonny Burke, Lee co-wrote the song “He’s a Tramp” and provided the voice for “Peg” as well as three other characters: Darling, the woman who owns Lady, and Si and Am, the malicious Siamese cats.

“Walt asked if I would mind if they named the character [Peg] after me, then explained the reason for the request,” Lee told The Times some years ago. “Mamie Eisenhower was our first lady at the time, and she always wore bangs. . . . The little dog has bangs and her name in the script was Mamie, so Walt was afraid someone might think we were being a little less than polite about the first lady. That’s why I have the honor of having the character named after me.”

It was her work in “Lady and the Tramp” that led decades later to one of the biggest fights in her life.

In 1991, she won a legal judgment against Disney after she sued for a portion of the profits from the videocassette sale of the movie, citing a clause in her contract with the studio barring sale of “transcriptions” without her consent.

And just last week, a Los Angeles Superior Court judge gave preliminary approval to a $4.75-million settlement between Vivendi Universal’s Universal Music Group and as many as 300 artists in a battle over royalties. Lee was the lead plaintiff in that suit, stemming from her years recording for Decca, which Universal now owns after a series of takeovers.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if she thought, ‘I accomplished that. That was the last big thing. Now I can go,’ ” her attorney, Cyrus V. Godfrey, said Tuesday.

Lee had told him, Godfrey said, that “the case was important to resolve the issues not only for herself but for other artists.”

Though Lee will be remembered for her sultry, sophisticated stage presence, she was still a North Dakota farm girl.

“There was a lot of down-to-earth that was part of her too,” said Foster, her daughter. Until her health began to decline, she was an excellent cook and an avid gardener.

“She had a terrific sense of humor, an absolutely fabulous one,” Foster said. Her mother even expressed that sense of humor in a song about her childhood abuse in her song, “One Beating a Day.”

“I think it took her a long time to get over and deal with that part of her life,” Foster said. “But once she was able to put it behind her, she was even able to joke about it. And of course, there’s very little humor in something like that.”

But her real gift was the music and her ability to connect with an audience.

“Her phrasing and her style musically were impeccable,” said Jerry Leiber, who with Mike Stoller wrote one of Lee’s Grammy-winning songs “Is That All There Is?”

‘She was very measured, even mannered, but still a great swinger. So much was contained, and yet you could sense the wildness in the swing.”

Lee once told an interesting story about the imagery that her voice elicited.

Songwriter “Alec Wilder used to make a strange analogy about my voice,” Lee said. “He said I had a voice like a streetwalker you’d walk past, but if you ever stopped, you’d never leave. . . .

“Now, I don’t exactly think of myself as a streetwalker, but I think I know what he means: the sensuousness.”

Her marriage to Barbour ended in divorce, as did marriages to actors Brad Dexter and Dewey Martin and musician Jack Del Rio.

In addition to her daughter, Lee is survived by grandchildren David Foster, Holly Foster-Wells and Michael Foster, and by three great-grandchildren.

Services will be private.

Times staff writers Ann O’Neill and Barbara Thomas contributed to this report.

From the Archives: Orson Welles, Theatrical Genius, Found Dead at 70

From the Archives: Dr. Bunche, Given Nobel Peace Prize for Work in U.N., Dies

From the Archives: Jazz Great Duke Ellington Dies in New York Hospital at 75

From the Archives: Julie London; Torch Singer, Movie and Television Actress

From the Archives: Ella Fitzgerald, Jazz’s First Lady of Song, Dies

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.