From the Archives: Ossie Davis, 87; Actor Played a Powerful Role in Civil Rights Gains

Ossie Davis, the baritone-voiced actor, director, playwright and civil rights activist whose commitment to teaching the lessons of black history added depth to a distinguished career that ranged from the Broadway stage to the films of Spike Lee, was found dead early Friday in his hotel room in Miami Beach, where he was filming a movie. He was 87.

Davis’ body was discovered when he failed to open the door for his grandson at the Shore Club, a luxury hotel. According to Miami Beach Police Department spokesman Bobby Hernandez, the actor, who had a cardiac pacemaker, appeared to have died of natural causes.

Davis had arrived in Florida on Monday to begin filming his part in an independent movie called “Retirement” with co-stars George Segal, Rip Torn and Peter Falk. Davis had completed two scenes, including a strenuous dance number Thursday, his agent, Michael Livingston, said Friday. “Retirement,” a comedy, would have been Davis’ 81st movie as an actor.

Davis, who lived in New Rochelle, N.Y., with his wife of 56 years, actress Ruby Dee, was best known in recent years for his roles in Lee’s raucous films about black urban life.

As a director, Davis paved the way for a wave of black-themed movies in the 1970s with “Cotton Comes to Harlem,” an adaptation of the Chester Himes detective novel. Released in 1970, it was the first major crossover film demonstrating that white audiences would support movies about African Americans.

Inspired by such socially conscious artists as Paul Robeson and Langston Hughes, Davis played a visible role in key events of the modern civil rights movement, including serving as master of ceremonies with Dee at the 1963 March on Washington, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech. The actor also gave the eulogy at the funeral of Malcolm X, the fiery black leader assassinated in 1965.

Davis thought of himself primarily as a writer. He wrote essays, children’s books and plays. His greatest success as a playwright was the 1961 race satire “Purlie Victorious,” a classic contemporary black drama that ran on Broadway before it became “Purlie,” a Tony- and Grammy-winning musical, and a movie.

“I am essentially a storyteller, and the story I want to tell is about black people,” Davis once said. “Sometimes I sing the story, sometimes I dance it, sometimes I tell tall tales about it. But I always want to share my great satisfaction at being a black man at this time in history.”

Last year he and Dee received Kennedy Center honors for their lifetime achievements in the arts. In 1995, President Clinton gave them the National Medal of the Arts.

Entertainer Harry Belafonte, who shared the platform with Davis at many civil rights events over the years, called his friend “a remarkable warrior.”

“He was very courageous in his commitment to social and political causes,” Belafonte told The Times on Friday.

“He walked in the shadow of men like Paul Robeson, W.E.B Du Bois, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. He was the embodiment of all those courageous people,” Belafonte said. “I think he worked very hard at passing on to subsequent generations not only a deep and rich sense of their history but encouraged them to become more noble in their demands of life, governance and society. I think African Americans in particular are huge beneficiaries of his presence in our midst.”

Davis’ struggles as a black man in a racist society began in Cogdell, Ga., where he was born Dec. 18, 1917. The eldest of five children of a railroad worker who later took up herbal medicine, he was named Raiford Chatman Davis. His parents called him R.C.

When his mother registered his birth, the county clerk misunderstood her and thought she said “Ossie” instead of “R.C.” As Davis recounted in his memoirs, “The man was white. Mama and I were black and down in deepest Georgia. So the matter of identification was settled. Ossie it was, and Ossie it is till this very day.”

He grew up amid the gruesome realities of ritual lynchings and the Ku Klux Klan. But what he found more damaging to his developing sense of manhood was the psychological violence inherent in everyday encounters with the white world. He wrote frankly about these – and his acquiescence in what he called “niggerization” – in a 1998 memoir, “With Ossie & Ruby, In This Life Together.”

When he was no more than 6 or 7 years old, Davis recounted, he was walking home from school when two white police officers called out to him. They took him to the station, where they teased and laughed at him for an hour. But Davis was not afraid or upset. “They laughed at me,” he said, “but the laughter didn’t seem mean or vindictive.”

At one point, one of the officers picked up a bottle of cane syrup and poured it over Davis’ head. “They laughed as if it was the funniest thing in the world, and I laughed, too,” Davis recalled. “Then the joke was over, the ritual complete. They gave me several hunks of peanut brittle and let me go.”

He didn’t think enough of the incident to report it to his parents. (“They were just having some innocent fun at the expense of a little nigger boy,” he wrote of his thoughts at the time). But it left a deep psychological scar that pervaded his sense of purpose when he grew into an artist and activist.

“The process of niggerization is always a two-sided one, shared by two consenting individuals, one black, one white,” Davis wrote in his memoir. “The price of consent exacted from the black person, however, can be his life, livelihood and all that he holds dear.”

In high school, Davis had the good fortune to have an English teacher who introduced him to the joys of language. “She spoke as if her words tasted sweet,” Davis recalled. He began to act in class plays, operettas and pageants and soon was reading Shakespeare for the fun of it. He tried his hand at writing plays.

He finished high school in the depth of the Depression with two scholarship offers – to Savannah State College in Georgia and the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama – but he could not afford to pay his share of the expenses and turned them down.

His family eventually saved enough money to send him to Washington, D.C., where he could live with relatives while attending Howard University.

There, his interest in the theater was encouraged by poet Sterling Brown and philosopher Alain LeRoy Locke, both leading figures in the Harlem Renaissance, the cultural movement of the 1920s and ‘30s that celebrated black consciousness in the arts.

Locke urged Davis to spend a summer working for a Harlem theater company that produced only plays by, for and about blacks. Going to Harlem struck Davis as such a wonderful idea that he left Howard in 1939 without his degree and presented himself to the Rose McClendon Players. Dick Campbell, a former vaudevillian who ran the company, was so impressed by Davis’ deep voice and dignified manner that he quickly cast him as a minister in the next production. Davis acted in four plays with the company over the next three years.

In Harlem he was surrounded by the leaders of the struggle against racial inequality, including union leader A. Philip Randolph, writer James Weldon Johnson, Rep. Adam Clayton Powell Jr. and Du Bois. Davis began to read the Daily Worker for its critiques of anti-Semitism and racism and attended meetings of the Young Communist League.

Then World War II interrupted. The Army sent Davis to Liberia, where he served at the Army’s first black station hospital before being transferred to Special Services to write and produce stage shows for the troops.

Shocked by the Nazis’ treatment of Jews and frustrated by the inequities he saw in the Army, he returned to civilian life in 1945 determined to use his talents to change America.

He made his Broadway debut the next year in “Jeb,” a Robert Ardrey play about a disabled black veteran who attracts the ire of the Ku Klux Klan when his old plantation boss puts him to work not in the field but in the office as a bookkeeper.

Although critics singled out Davis’ performance for praise, “Jeb” closed after only nine performances. But the show introduced Davis to Dee, an understudy who took over the role of Jeb’s girlfriend. He and Dee went on to appear together in the American Negro Theater production of “Anna Lucasta” on Broadway. Their relationship bloomed on tour and they were married Dec. 9, 1948.

Two years later, the two made their movie debuts in “No Way Out,” writer-director Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s gripping race drama that starred Richard Widmark and introduced Sidney Poitier to film audiences.

During the 1950s, Davis and Dee also began a long and rewarding association with Moe Foner, the impresario of Local 1199 of what was then the Retail Workers Union. Believing in the power of the arts to educate workers, Foner recruited Dee and Davis to stage plays for union members.

One of the plays Davis wrote and directed was “The People of Clarendon County,” about one of the cases that led to the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision prohibiting school segregation. He also wrote dramas about the brutal 1955 killing of black teenager Emmett Till, the Montgomery bus boycott and King, whose nonviolent philosophy earned him the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize.

The plays were powered by an array of emerging talents. “On [one] occasion I remember coming to the office and finding Ossie supervising a rehearsal of a cast that included Ruby, Harry Belafonte, Sidney Poitier, Will Geer and Ricardo Montalban,” Foner wrote in his memoir, “Not for Bread Alone.” “One of the actors took me aside and said, ‘There’s no one in the world who could get all these people together to do this – except Ossie.’ ”

In 1959 Davis replaced Poitier in Lorraine Hansberry’s “A Raisin in the Sun,” the first play by a black woman to reach Broadway. Emboldened by Hansberry’s success, Davis finished a play he had begun to write years earlier.

Davis had started out writing an angry, passionate play about the evils of racism, stimulated by painful memories of his boyhood encounter with the police. But he gradually realized that what he had to write was a satire, “a minstrel show with a high purpose.”

The result was “Purlie Victorious,” which opened Sept. 29, 1961, at the Cort Theatre in New York City. Davis starred as Purlie, an unlicensed preacher and erstwhile philosopher who returns to southern Georgia with a plan to buy his old plantation master’s barn and turn it into a racially integrated church.

Other roles were filled by Dee as a naive country girl who becomes Purlie’s love interest; Alan Alda as the plantation owner’s shockingly liberal son; and Godfrey Cambridge as the master’s “Deputy-for-the-Colored,” an Uncle Tom.

“The play was seen as falling somewhere between folk comedy and a social document, a gleeful satire of all the popular stereotypes of Negro-white relations in the South in particular and in the United States as a whole,” Clinton F. Oliver wrote in Contemporary Black Drama. “But, like many great comic works, say, Moliere’s ‘Tartuffe’ or Ben Jonson’s ‘Volpone’ or Gogol’s ‘The Inspector General,’ ‘Purlie Victorious’ is an angry play, rooted in the basic indignation of its author.”

Du Bois, then 93, was in the audience on opening night and declared the play a winner. King offered similar praise after attending the 100th performance. But “Purlie” made no money and closed after eight months and 261 performances. Jayne F. Mulvaney, writing in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, said its failure was the result of tepid response from white theatergoers.

Davis adapted the play for the screen in 1963 under the title “Gone Are the Days,” which featured much of the original Broadway cast. But the work found its widest audience a decade later when Davis turned it into a Broadway musical. Nominated for best musical of 1970, “Purlie” featured music by Gary Geld and lyrics by Peter Udell and starred Cleavon Little and Melba Moore, who won Tonys for their performances.

Malcolm X, in apparent defiance of Muslim leader Elijah Muhammad’s disapproval of the theater, attended a performance of the original “Purlie Victorious” in 1961. “He said he liked the show because he felt that black folks laughing at white folks was revolutionary – the highest kind of struggle he could imagine,” Davis recalled in his memoir.

Over the next few years, Davis grew close to Malcolm, whose intelligence and oratorical gifts he admired. He and Dee were among the last people the charismatic leader visited before his murder in 1965. Malcolm, who had begun to soften his views of whites, was in the midst of a speech explaining his ideas for reaching out to the mainstream of the civil rights movement when he was shot dead by three gunmen, all Muslims.

In his eulogy, Davis felt compelled to correct the image of a man who had been derided as a hate-mongering racist, to “let the world know what Harlem felt ... about this brother.”

“Did you ever talk to Brother Malcolm? Did you ever touch him, or have him smile at you? Did you ever really listen to him? Did he ever do a mean thing? Was he ever himself associated with violence or any public disturbance?

“For if you did, you would know why we must honor him: Malcolm was our manhood, our living, black manhood! This was his meaning to his people. And, in honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves.... And we will know him then for what he was and is – a prince – our own black shining prince! – who didn’t hesitate to die, because he loved us so.”

That characterization of Malcolm as a “black shining prince” shook whites as well as blacks and is cited today in discussions of the slain orator’s importance.

“Nothing equals the gift Ossie brought this country in his understanding of who Malcolm X was,” Belafonte said Friday. “Millions of people look at who Malcolm was because of what Ossie Davis said. He caused them to see him in a new and profound light.”

Davis later played himself as the eulogist in the extended coda of Spike Lee’s 1991 movie “Malcolm X.”

Over the next decades, Davis tried to use his stature among blacks and in the entertainment world to influence the portrayal of African Americans. He chose roles that enriched the understanding of black history and wrote books for young readers about such black heroes as King, Hughes and Frederick Douglass.

In the 1970s Davis began to direct movies, the most notable of which was “Cotton Comes to Harlem.” The action comedy starred Godfrey Cambridge and Raymond St. Jacques as two black cops determined to stop a scam artist who was stealing from Harlem’s poor. Its success, Times critic Charles Champlin wrote some years later, “led to a bandwagon of black films,” including the popular “Shaft” series.

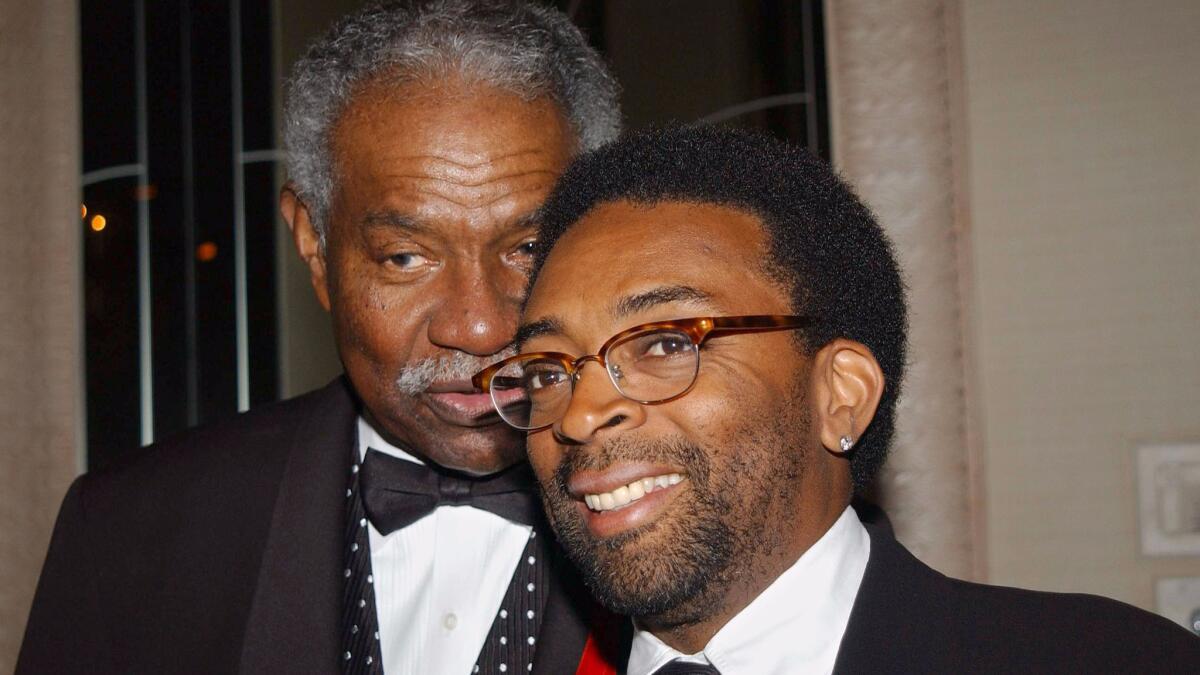

Davis’ collaboration with Lee brought about a renaissance in his career as an actor. Lee chose him to play a coach in “School Daze,” a frank comedy about tensions among undergraduates at an all-black university that was released in 1988. The director featured Davis in several other movies, including “Do the Right Thing” (1989), “Jungle Fever” (1991) and “Get On the Bus” (1996).

“I believe that in some sense I do represent a floating father figure in Spike’s films,” Davis once told a London newspaper. “I provide him with the parameters that he will not go beyond. I think he says to himself, “If Ossie understands it, then the rest of the old black folk will understand.’ ”

In addition to Dee, who was on location in New Zealand when he died, Davis is survived by three children, Nora Day, Hasna Muhammad and Guy Davis; and seven grandchildren. Funeral plans are pending.

From the Archives: Ella Fitzgerald, Jazz’s First Lady of Song, Dies

Ruby Dee, acclaimed actress and civil rights activist, dies at 91

From the Archives: Mayor Who Reshaped L.A. Dies

Ricardo Montalban dies at 88; ‘Fantasy Island’ actor

Peter Falk dies at 83; actor found acclaim as ‘Columbo’

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.