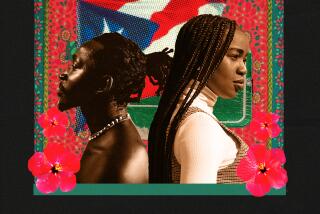

California set to be first state to protect black people from natural hair discrimination

Kari Williams has worked to make her natural hair salon a refuge for black Angelenos, including those who’ve felt pressured to alter their hairstyles to hold on to a job.

Some customers have asked her to cut their locs — short for dreadlocks — because their bosses deemed them unacceptable. Others hadn’t worn their natural hair in so long they forgot what it looked like. That’s why Williams welcomes proposed state legislation that could soon make California the first state to protect black employees from discrimination based on hairstyles.

“It’s important to me as a black woman,” said Williams, who owns Mahogany Hair Revolution, a hair salon in Beverly Hills. “Our skin color and our hair have been used as ways to continue to keep us disenfranchised.”

The CROWN Act, which passed the state Senate in April, was approved by the state Assembly on Thursday. It would outlaw policies that punish black employees and students for their hairstyles. Supporters say the bill’s acronym reflects its intention: creating a respectful and open workplace for natural hair.

If signed by Gov. Gavin Newsom, the bill would legally protect people in workplaces and K-12 public schools by prohibiting the enforcement of grooming policies that disproportionately affect people of color, particularly black people. This includes bans on certain hairstyles, such as Afros, braids, twists, cornrows and dreadlocks.

The proposal by Sen. Holly Mitchell (D-Los Angeles), comes after Chastity Jones, a black woman from Alabama, asked the U.S. Supreme Court to hear her case in 2018 after she claimed to have lost a job offer because she refused to cut her dreadlocks.

In California, school officials in and around Fresno have sent black students home because of their curls and shaved heads. The Transportation Security Administration also ushered in new measures after facing allegations of “unnecessary, unreasonable and racially discriminatory” hair searches of black women at Los Angeles International Airport.

Nationally, black employees have filed several lawsuits, claiming to have lost jobs and faced discrimination in the workplace because of their hair.

RELATED: Black hair in Hollywood: Five women share their stories »

The CROWN Act would extend anti-discrimination protections in the Fair Employment and Housing Act and the California Education Code to include hair texture and styles. It also would amend the California government and education codes to protect against discrimination based on traits historically associated with race, such as hair texture and hairstyles — affirming that targeting hairstyles associated with race is racial discrimination.

New York City officially banned natural hair discrimination in February, saying that hairstyles are protected under the city’s existing anti-discrimination laws because policing black hair is a form of pervasive racism and bias. Lawmakers in New York and New Jersey also proposed legislation modeled after the CROWN Act in June.

The legislation comes 20 years after Sisterlocks, a San Diego-based natural hair care management company, successfully argued a case involving hair care discrimination. The company argued its practitioners shouldn’t be required to undergo 1,600 hours of training to obtain a state license because natural hair care wasn’t taught in cosmetology schools and is, in large part, a cultural practice.

“This legislation could potentially set a precedent nationally as our case did,” said JoAnne Cornwell, the founder of Sisterlocks.

Mitchell wrote the proposed legislation, SB 188, and before the Senate unanimously passed it, she described the bill’s purpose as twofold: to dispel myths about black hair, its texture and the black hair experience, and to challenge what constitutes “professionalism” in the workplace.

“Eurocentric standards of beauty have established the very underpinnings of what was acceptable and attractive in the media, in academic settings and in the workplace. So even though African Americans were no longer explicitly excluded from the workplace, black features and mannerisms remained unacceptable and ‘unprofessional,’” said Mitchell, a black woman.

The bill states that “blackness” and its associated physical traits — dark skin, kinky and curly hair — have long been equated to “a badge of inferiority” because of racist ideologies. And when black employees conform to narrow, Eurocentric ideas of “professionalism” by altering their appearances, there are serious economic and health consequences because of high costs and harsh chemicals, the bill says.

“Racial capital refers to this idea that the farther away you are from Eurocentric standards, the harder it is for you,” said Nourbese Flint, policy director for Black Women for Wellness, a reproductive justice education and outreach organization. “If you are thinner with straighter hair, lighter skin and lighter eyes, that opens up different spaces for you. The farther away you are from [those standards], the harder it can be to get into certain spaces of privilege.”

Flint said her group has worked on issues relating to hair care partly because black women are the nation’s biggest consumers of hair care products and because altering one’s hair can come with serious health consequences.

“We know the hair care products that black women use have some of the most toxic chemicals on the market,” Flint said, adding that the most hazardous chemicals are found in products for permanently straightening hair. “But in order for us to conform to [Eurocentric] standards, we end up having to use a lot of different chemicals that are harmful to our health.”

A 2018 peer-reviewed study examined the hazards of hair products, including hot-oil treatments, anti-frizz polishes, root stimulators and relaxers. The study, prepared by the Silent Spring Institute, which studies women’s health and the environment, found that the products were made with chemicals linked to asthma, birth defects, reproductive issues and cancer.

These health concerns, in part, have inspired some hairstylists to emphasize education, so their customers wouldn’t have to choose between their hairstyles and their health.

Williams, the salon owner, said she has a doctorate in trichology, which focuses on the care of the hair and scalp, to help women deal with the aftermath of straightening and chemically treating their hair.

“The cosmetology schools spend 1,600 hours teaching us how to destroy our hair. We don’t really have formal instruction and training on how to take care of our hair, so I wanted to position myself as a resource for that,” said Williams, a member of the California Board of Barbering and Cosmetology. “That led me to opening my salon.”

In Stockton, Valonne Smith left a career of working in biotech and business development to open Natural Do, a salon where she teaches people about the health benefits of going natural.

“A reason people go natural is because they’re losing their hair, which is either from the chemicals, the pulling and the tightness of the weaves,” Smith said.

Michelle Laron Bryant grew up in Los Angeles practicing braids on dolls while her grandmother taught her to care for her natural hair. Now Bryant, a licensed cosmetologist and author of “Celebrating Natural Hair: For Braids, Twists, Locks and Sisterlocks,” is a trainer with Sisterlocks.

When she had her daughter, Bryant wanted to model natural hair at home the same way her grandmother did for her. She saw other moms do the same.

“For a long time, I worked with a lot of mothers and daughters who were interested in being natural at a time when it wasn’t encouraged because we’re taught that in order to get hired or be acceptable, you had to alter our hair texture,” Bryant said. “We literally had to build a community so we could support each other.”

SB 188 is sponsored by the CROWN Coalition — a national alliance composed of the National Urban League, Western Center on Law & Poverty, Color of Change and Dove. Groups such as the American Civil Liberties Union of California, Black Women Organized for Political Action, the California Black Chamber of Commerce and the California School Boards Assn. have also supported the legislation.

That pleases Williams, the salon owner, who once met Mitchell in a campaign office on Crenshaw Boulevard in South Los Angeles. She remembers being excited to see a black woman with locs talking about the ways people can feel confident, beautiful and healthy wearing their natural hair.

“Throughout history, our hair has been used against us,” Williams said. “It’s tough to move forward when our identity has been attacked.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.