Yosemite Valley closed as deadly Ferguson fire grows, sending smoke into park

A stream of cars, campers and trailers flowed out of Yosemite National Park on Wednesday morning as the deadly Ferguson fire inched ever closer and prompted officials to order areas of the park closed.

Visitors were given until noon Wednesday to evacuate Yosemite Valley, the heart of the 1,200-square-mile park. Officials have also closed Highway 41, the north-south artery that carries travelers from Southern California to Yosemite, and Glacier Point Road.

The areas are expect to reopen Sunday, according to officials.

The Ferguson fire, which has raged west of Yosemite since July 13, grew to 38,000 acres as of Wednesday and was 25% contained. At its closest point, the fire is two miles from the park, Yosemite spokesman Scott Gediman said.

Heavy smoke from the blaze has blanketed the valley and created air quality conditions worse than in Beijing, China’s heavily polluted capital, he said.

“With this hot, dry weather pattern you just got the smoke sitting here,” Gediman said. “The air quality fluctuates throughout the day but it’s really poor midday — noon to 6 p.m.”

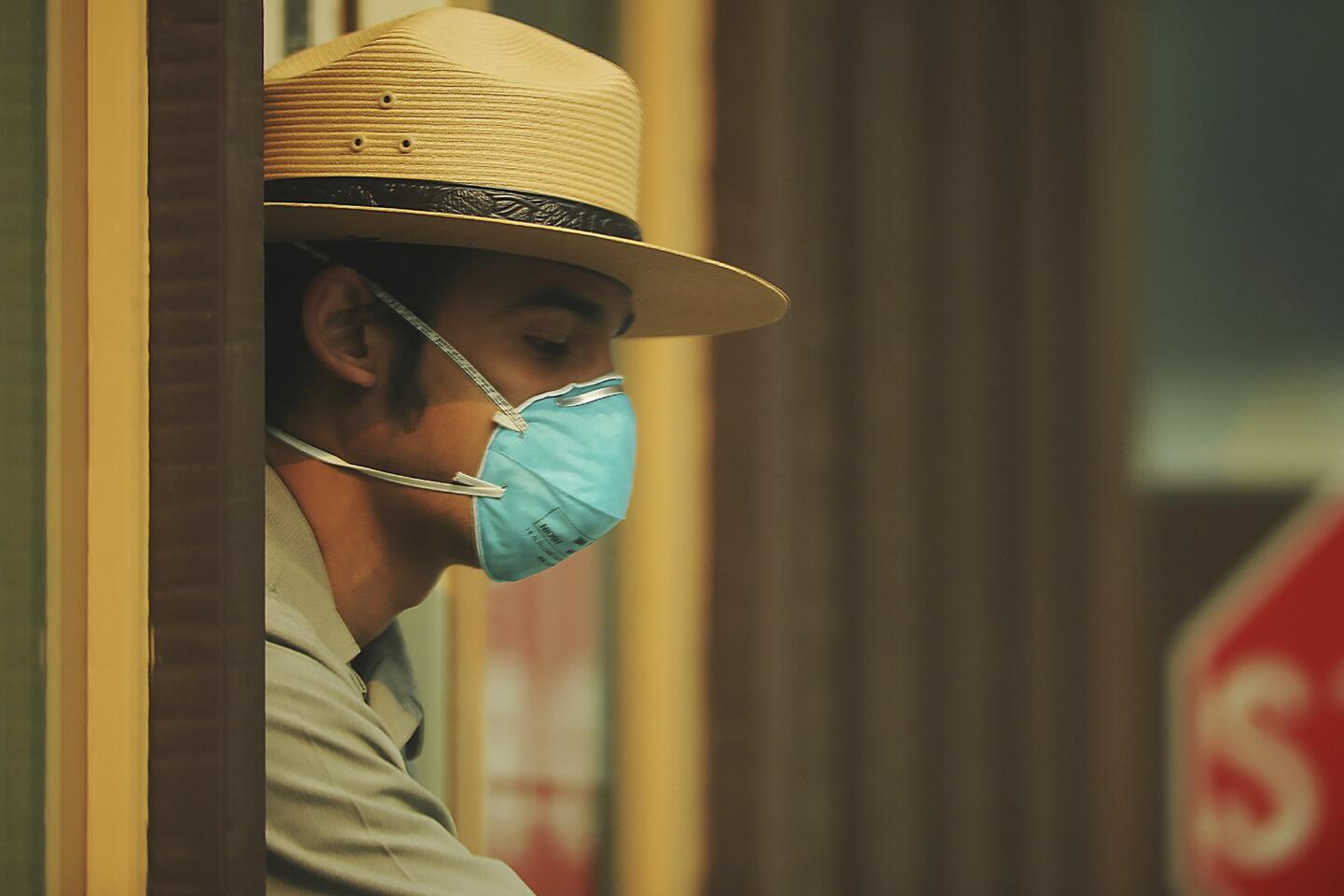

Officials have been handing out high-grade filtration masks and set up “clean air” centers around the park where employees and visitors can get a break from the smoke-filled air, Gediman said. Still, after days in the smoke, Gediman said his voice has become raspy and he feels a dryness in his throat.

On Tuesday night, officials taped evacuation notices on hotel doors and campers. Even before the order went out, however, visitors had begun packing up when they saw dark clouds of smoke filling the sky.

“It’s not a panic situation,” Gediman said. “The fire is not in Yosemite National Park. There are no flames in the park.”

Two areas in the northern part of the park, Tuolumne Meadows and Hetch Hetchy, remain open.

For the last few days, an inversion layer of warm air has kept the fire relatively calm. But in the early hours Tuesday, fire officials said, a shift in the winds pushed the fire into an area with many dead trees. That sent embers flying past the firefighters’ break line, sparking several spot fires that grew into a large fire of more than 500 acres, according to U.S. Forest Service spokesman Jim Mackensen.

The unexpected fire behavior prompted officials to order mandatory evacuations in the Lushmeadows area of Mariposa County.

“It’s like in a fireplace,” Mackensen said. “You close that damper. There’s no smoke going up. It just kind of hangs and fills the house full of smoke. But you open that damper and a window and the heat from the fire goes roaring up the chimney. It pulls in fresh air from the bottom and the fire starts to breathe again. That’s essentially what happened today.”

More than 3,000 people are battling the blaze, aided by dozens of water-dropping helicopters, water trucks and bulldozers.

One of the biggest challenges in fighting the Ferguson fire is the terrain. Steep inclines and rocky canyons have made it difficult to approach some portions of the fire.

“It’s not worth putting people in some of these areas,” Mackensen. “It’s just too dangerous.”

One firefighter operating a bulldozer died when his vehicle rolled down a hillside, and six others have been hurt — their injuries ranging from back strains to broken bones and heat exhaustion, Mackensen said.

One particularly precarious area where the fire is burning was named the Devil’s Gulch many years ago by the area’s first explorers, fire information officer Rob Deyerberg said.

The terrain is “only a place where the devil would live,” Deyerberg said. “We will not put firefighters down in the worst places. That’s where they build their lines, develop their plans of where can we catch this fire on our terms.”

Part of the plan is to bring the fire into Yosemite Park, where the terrain is less difficult to negotiate.

The fire, which is moving east toward Yosemite, is fueled in part by large trees that have been killed by bark beetle infestation, Deyerberg said. Years of drought and recent drought-like conditions have allowed the invasive insect’s population to explode.

“Dead trees are drier,” Deyerberg said. “Dry fuel burns hotter and faster.”

These frail trees send embers and burning pieces of vegetation flying all over the forest, helping the fire to spread, he added.

UPDATES:

12:55 p.m.: This article was updated with comments from Yosemite spokesman Scott Gediman and U.S. Forest Service spokesman Jim Mackensen

This article was originally published at 7 a.m.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.