As crime and drugs recede, MacArthur Park is going upscale, and many residents feel left behind

The demographics of MacArthur Park have shifted, and the average rent for apartments have increased.

When she moved to her apartment near MacArthur Park, Maria Benitez quickly discovered no one turned down her street by accident.

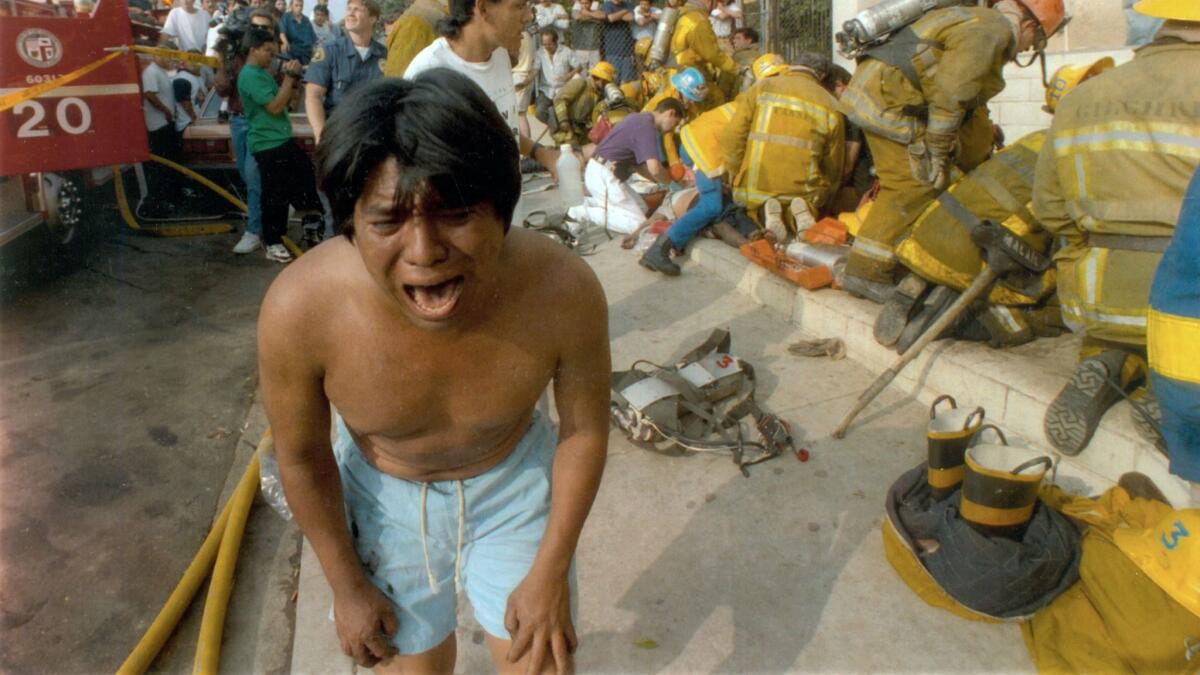

Some came to buy crack cocaine or to hunt for rival gang members. In 1993, a group of gang members in her neighborhood set fire to an apartment complex three doors down from Benitez. Two pregnant women and seven children died.

“You did two things then: go to work and go back home,” she said. “You didn’t go out because it was too dangerous. There were a lot of gangs and a lot of shootings.”

Now, Benitez stands on the balcony of her apartment on Burlington Avenue, looking out over her changing neighborhood. Construction workers next door hammer nails into wooden beams as they renovate a Victorian duplex. Electricians across the street install lights in a building with an “apartment for rent” sign. A young Korean couple dressed in vintage 1970s clothes take a peek inside.

Gentrification has swept across much of Los Angeles in the last decade, but few places seem primed to change as fast as the Westlake district just west of downtown L.A.

One of the most densely populated areas in the nation — with more than 100,000 people crammed into nearly three square miles — Westlake was for years considered a cautionary tale for L.A., a world controlled by street gangs. It was a first stop for immigrants from Mexico and Central America, where Spanish was more common than English.

To outsiders, that image remains — Netflix set much of its recent Will Smith movie “Bright,” which involves a dystopian L.A. of gang-banging orcs and humans, in the neighborhood.

But on the ground, the reality is different. Stylish lofts, swanky nightclubs, bars and theaters have popped up in the area as young artists and professionals move in. Slowly but steadily, the demographics of MacArthur Park have shifted. The Asian population has grown while the Latino population has dropped from 74% to 68% between 1990 and 2015, according to the American Community Survey.

Though the district remains predominantly Latino, some longtime residents worry about the future — and whether they have a place in it — if this upscale boom continues.

In the last seven years, the average rent for a studio jumped from $1,782 to $2,600 in a neighborhood where the majority of residents are renters. Developers are also moving in — and of the planned projects, one stands out the most.

Dubbed The Lake on Wilshire, or “The LOW,” the project involves converting a 14-story medical office building into a 220-room hotel, and construction of a 41-story apartment tower that will include restaurants, bars and 49 affordable housing units, and a 70,000-square-foot, multicultural performing arts center.

“This could be the beginning of drastic changes for the neighborhood,” said Gerardo Sandoval, an ex-MacArthur Park resident and associate professor at the School of Planning, Public Policy and Management at the University of Oregon. “The question should be: Who is that development going to be for?”

It’s a question that is roiling the streets around MacArthur Park.

“When there was violence here, the investors left while we tried to make the area better,” said Jose Felix, a longtime resident and vice president of the MacArthur Park Neighborhood Council. ”Now the investors are returning. They’re opening nightclubs, bars and — what tugs at our hearts — newly built buildings that are displacing our people.”

Claudia Medina, an attorney with Eviction Defense Network, said the tell-tale signs of a neighborhood in mid-transformation are there.

She said low-income tenants have complained about landlords harassing them to move out — even going so far as offering them buyouts — while others have faced eviction lawsuits.

In December, 63-year-old Rosita Lopez and her husband faced eviction after allegedly violating their lease agreement. The couple were accused of having a two-burner butane countertop stove in their studio apartment without the landlord’s approval, according to the eviction lawsuit.

Medina, who successfully defended the couple, said the owner had filed a similar lawsuit against another tenant at the same building, near the edge of Westlake and downtown L.A.

The LOW is the vision of Dr. Walter Jayasinghe, a philanthropist and plastic surgeon with long ties to Westlake and other nearby neighborhoods such as Echo Park, Highland Park, Boyle Heights and South L.A.

Jayasinghe, who also founded the Sri Lanka Foundation, established the first 24-hour general clinics in Westlake, according to his profile on the project’s website. He made the ground-floor ballroom of his medical center at 1930 Wilshire, the site of the project, available to community groups. He also operated a free clinic that served the homeless population in downtown.

David Nahai, an advisor to Jayasinghe on the Lake on Wilshire, said the project is being embraced by the community and stands out from other developments that have popped up in the city over the years.

“This is not a situation where a developer is parachuting in to build a project, profit from it and leave, this is not that,” Nahai said. “We have a developer here who truly cares, deeply, about the home that he’s found and about the community that has embraced him and given him so many opportunities.”

He said the project comes with a long list of public benefits. Hundreds of thousands of dollars will go toward affordable housing and public safety. The mulicultural center will host concerts, lectures and plays. It will also act as a training and educational hub where residents can attend English and computer classes and other programs.

“There are so many things in such a big package of community benefits that’s coming with the project,” Nahai said. “So you take all those things and it tells you we are dealing with a unique situation here.”

Last February, the five-member MacArthur Park Neighborhood Council sent a letter to the city planner supporting the project because of the revenue and jobs it would produce, as well as the creation of 39 affordable housing units for very-low-income residents.

But when the council learned of the scale of the development, it requested more affordable housing units. The developer added 10 units, but those were later changed to workforce housing units, defined as the annual income of a household that does not exceed 150% of the area median income as determined by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

In L.A. County, the median household income is $64,300; in Westlake it is only $26,000. Affordable housing advocates say that makes it hard for the area’s poorest residents to qualify for the kind of housing that developers and city officials want to bring to the area.

Nahai said they have provided more than what opponents have asked for and have tried to meet their needs as well as those who have supported the project.

Margarita Lopez, the MacArthur Park Neighborhood Council president who moved out of the area in 2016 because she couldn’t afford her studio, sent a letter on Jan. 22 rescinding the group’s support of the project.

The letter was sent a week in advance of an L.A. City Council meeting at which affordable housing advocates and area residents hoped the 15-member council would address their concerns.

The council voted in favor of the project, including Councilman Gil Cedillo, who represents the neighborhood.

Cedillo has been a vocal supporter of projects that will lead to more affordable housing and bring residents with a mix of incomes.

Last month, he urged the planning and land use management committee to vote for the project so that the City Council could address it.

“This is an example of what development will be needed if we’re going to address the challenges to this city with respect to affordable housing and homelessness,” he told the committee.

Cedillo said about 650 units of affordable housing have been built near the Lake on Wilshire site to address displacement concerns and that the developer has provided more than $2 million to New Economics for Women, a nonprofit that assists single mothers. The money would go toward La Posada, a women’s shelter.

Sandra Villalobos, a La Posada representative, said she supported the project and spoke at the committee meeting.

“Moving forward with this project would really support 60 women who came in homeless and their children,” she said. “The project will generate jobs in the community that would benefit not only the women who are going to be living in the community but also outside of the community.”

“This project is the most relevant project in the last 25 years,” said Franciso Rivera, former director of El Rescate, a nonprofit that provides immigration assistance to Central American immigrants. “It’s a magnificent project.”

Cedillo also spoke out against those who have criticized the project and his efforts to help the area.

“You would think we would be carried on the shoulders of the local community, but it is not perfect, it does not provide free rent indefinitely for an important group that resides in the planned project,” Cedillo said at the meeting last month.

“That’s their demand, and anything short of that is all or nothing,” he added.

MacArthur Park is in many way a barometer of Los Angeles’ evolution over the last century.

In the 1920s, the area around the park was dotted with mansions and luxury hotels. It was home to movie stars, oil magnates and media barons such Harrison Gray Otis, publisher of the Los Angeles Times. It was the place to be and be seen.

But by the 1960s, the neighborhood was in decline.

When Benitez settled in MacArthur Park in 1973, her neighbors were mostly Filipinos. Over the years, she watched as they left the area, pushed out by the growing Mexican community. By the mid-1980s, an influx of immigrants fleeing the civil wars in Central America settled in the neighborhood.

From this tiny, overcrowded area emerged two violent street gangs: 18th Street and MS-13.

Benitez and other neighbors on Burlington Avenue recall those violent days when gangs walked openly with guns and turned streets into drug markets.

Standing behind a half-open door, Rosa Marroquin, 67, a longtime resident, remembers going out very little because of the danger.

“You’d always get robbed,” she said. “There were a lot of drug use then, and it’s not like it was done in secret too. The drug deals would happen out in the open.”

Maria Melendez said she remembered cowering with her children when gang members began shooting at one another, just feet away from her apartment.

“It was like playing a game of Russian roulette,” she said. “At any moment you wondered if it was going to be your turn to die.”

In 1993, 18th Street gang members set fire to an apartment complex on Burlington Avenue. The attack was payback against a landlord who refused to let them sell drugs. The blaze killed 10, including seven children and two pregnant women. It was one of the deadliest arson fires in the city’s history.

Even after the deadly blaze, the gang continued to terrorize the area.

On Sept. 15, 2007, an infant was killed by a stray bullet near the intersection of 6th Street and Burlington Avenue. The shooting occurred when a street vendor refused to pay $50 in “rent.”

At the time, the 18th Street gang was offering protection from rival gangs in exchange for kickbacks from illegal sales of narcotics, fake green cards and driver’s licenses. They also targeted vendors for using the sidewalks and streets to make sales.

That same year, the city started to revitalize the area. Free concerts were held at Levitt Pavilion in MacArthur Park. The paddle boats had returned. The LAPD launched what turned out to be a successful crackdown on drug dealing and prostitution in the park.

The following year, $2.5 million went toward an artificial-turf soccer field, stadium lights, picnic tables and a children’s playground, in the hope of luring families back.

Standing outside his affordable apartment complex, Isaiah Teal, 21, spoke to his girlfriend, standing on the balcony. A woman walked her dog as the sun began to dip. He’s come to love the area and is fascinated by the vendors who still hustle across from the park. But he’s not sure if he will be able to stay as rents rise.

“There’s really nothing bad about it,” Teal said. “You can find everything here.”

For more Southern California news, follow @latvives on Twitter.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.