Complaints of drinking, abusive behavior dogged USC medical school dean for years

USC’s football coach was fired after an L.A. Times investigation about his alcohol use in previous coaching jobs. (July 26, 2017)

USC faced a choice five years ago: Keep Dr. Carmen Puliafito at the helm of the Keck School of Medicine or replace him.

As dean, Puliafito had brought in star researchers, raised hundreds of millions of dollars and boosted the school’s national ranking — all critical steps in USC’s plan to become an elite research institution.

But what might have been an easy decision to renew his appointment was complicated by a groundswell of opposition from the medical school’s faculty and staff.

Keck employees had complained repeatedly about what they considered Puliafito’s hair-trigger temper, public humiliation of colleagues and perceived drinking problem, and many were adamant he be removed, according to current and former university employees as well as four letters of complaint reviewed by The Times.

The people who spoke to The Times include a former USC administrator who handled personnel grievances, the medical school’s former human resources director and prominent faculty members.

‘An embarrassment to our school’

“As a representative of USC, the Dean is an embarrassment to our School and the University,” one Keck professor wrote in a March 2012 letter to the university provost.

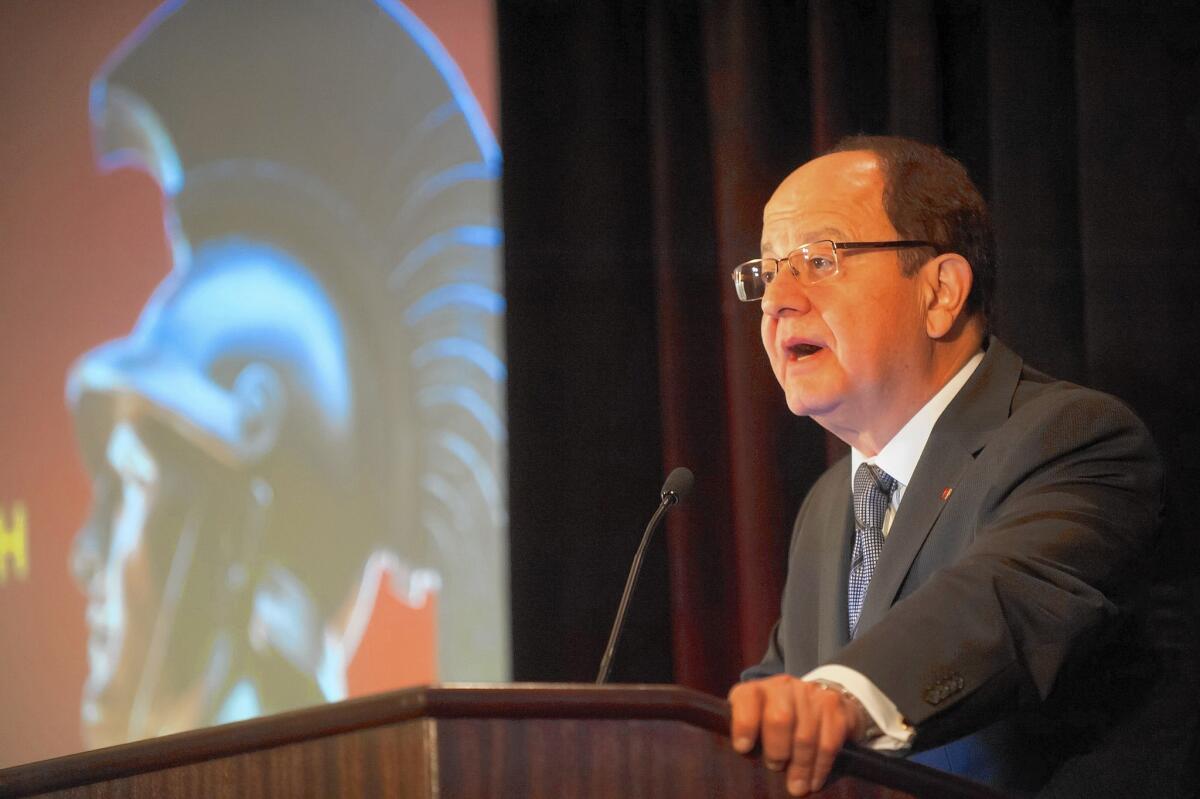

Still, USC President C.L. Max Nikias opted to reappoint Puliafito, giving him a new five-year term with an annual salary of more than $1 million.

Puliafito’s problems escalated. As The Times has reported, he partied with a circle of addicts, prostitutes and other criminals who said he used drugs with them, including on campus.

Late Friday, hours after the newspaper informed USC it was preparing to publish this story, Nikias sent a letter to the campus community acknowledging that the university received “various complaints about Dr. Puliafito’s behavior” during his nearly decade-long tenure as dean.

Nikias didn’t provide details of the complaints but wrote that the university took disciplinary action against Puliafito and provided him “professional development coaching.” He didn’t specify when.

The president also offered his first public account of the circumstances of Puliafito’s abrupt resignation in the middle of the spring 2016 term, writing that he stepped down after Provost Michael Quick confronted him with new complaints about his behavior.

Do you have information about USC’s former med school dean? We want to hear from you »

Puliafito, now 66, was allowed to continue representing USC at official functions and remained on the faculty and hospital staff.

Nikias said Friday that at the time of the dean’s resignation, “no university leader was aware of any illegal or illicit activities, which would have led to a review of his clinical responsibilities.”

Over the last two weeks, Nikias and other university leaders have said they were stunned by the revelations about the former dean.

‘The difficulty of just being around him’

But interviews with two dozen of Puliafito’s former colleagues suggest that complaints about his behavior were widespread and that at least some reached USC’s upper management. The colleagues said Puliafito’s conduct hurt morale and posed a risk to the school’s reputation.

“There were complaints about his demeanor, behavior and manner,” said Jody Shipper, who headed USC’s equity and diversity office for more than a decade. She left in 2015.

James Lynch, who was the medical school’s human resources director for five years, said employees came to him “fairly regularly” about misbehavior by Puliafito, including rudeness and suspected drunk driving.

“Many of the people who worked for him complained about the difficulty of just being around him,” Lynch said.

Current Keck dean Dr. Rohit Varma told a gathering of medical school students this month that Puliafito had received treatment for alcoholism.

Puliafito did not respond to a request for comment. He previously told The Times he resigned of his own accord to pursue a job in private industry.

Concerns about him were contained in lengthy written evaluations in 2012 that were assembled to help determine Puliafito’s fitness for a second term.

“Everybody I knew trashed him, and he still got [re]hired,” said former USC ophthalmology professor Dr. Kenneth L. Lu, who moved to UCLA in 2014.

Many faculty members and staff agreed to speak about Puliafito on the condition of anonymity, citing concerns over their careers. Since The Times’ report, USC has hired a crisis management firm to handle press inquiries and instructed employees at Keck not to speak to the media. The school also asked that doctors at an affiliate, Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, refer all Times inquiries about Puliafito back to the university.

Several interviewed said they were speaking out of a desire to help the institution they loved. Most expressed shock at reports of the former dean’s drug use.

In 2007, then-Provost Nikias, who became president three years later, chaired the committee that selected Puliafito, a renowned ophthalmologist, as medical dean. Many of his new colleagues initially found him brilliant and noted his easy rapport with patients and students. He struck them as extremely hardworking and committed to elevating Keck’s national profile.

“In my mind, anytime I saw him, he wanted to make this school grow,” said Bill Watson, a former vice president for development who worked with the dean from 2010 to 2013.

He was prone to anger, however, many former colleagues said. Minor inconveniences sent him into screaming, red-faced rages at staff meetings, they said.

“The F-word was in every other sentence,” said one former professor. She said she heard a high-ranking Keck administrator vomit in the ladies’ room after one dressing-down by the dean.

‘The dean was a heavy drinker’

Lynch, the former human resources director, confirmed that Puliafito upbraided that administrator on several occasions. “It was certainly challenging, and she ultimately left,” he said. Reached by The Times, the woman declined to comment.

One Keck physician said some on Puliafito’s support staff consulted her professionally to cope with how the dean treated them.

“I literally put people on medical leave for stress … related to working with him,” the physician recalled.

Others were concerned that he was drinking too much at USC events.

“The dean was a heavy drinker,” Lynch recalled. “He was fond of martinis. He would have several.”

He said he never saw Puliafito “do anything particularly outrageous” but fielded multiple complaints from a female staffer disturbed that he was driving home from the events at which he’d been drinking.

“She was concerned he might get in an accident and hurt himself or someone else,” Lynch said. He didn’t want to confront the dean because he thought it would be counterproductive, he said, but he told the woman, “If you are concerned, why don’t you mention it to him?”

Lynch, who was human resources director from 2009 to 2014, said he encouraged faculty and staff to complain directly to Puliafito themselves and did not pass on Keck employees’ complaints to the university administration.

“It never occurred to me to do it,” he said.

While Puliafito’s personal behavior was distasteful, Lynch said, he was “an absolute genius” who was improving the medical school.

“He’s kind of a pain in the ass, but he gets results,” he said, adding that he felt administrators shared that view.

One senior faculty member said he phoned the provost’s office after an encounter in which Puliafito seemed to be intoxicated.

An administrator in the office who took down his complaint, he said, thanked him for making the report and assured him “it would be reviewed at the highest level.”

He said he was not told the outcome and assumed it was being handled confidentially.

Puliafito’s behavior caused some of his colleagues to leave. The medical school’s admissions dean, Erin Quinn, who had been at USC since the early 1980s, stepped down from “a position that I loved” in 2011 “because I couldn’t work under Dr. Puliafito’s leadership team.”

“It had changed from previous deans and compromised my values,” she said.

Glowing self-evaluation

When Puliafito’s first term was nearing an end, then-Provost Elizabeth Garrett asked Keck faculty to complete written evaluations of his tenure — a standard university practice and, in the provost’s words, “a crucial part of our evaluation of a dean’s effectiveness in leading the school.”

Puliafito submitted a 19-page self-evaluation in which he listed myriad accomplishments. He noted that he had raised more than $500 million in contributions, recruited prominent researchers from Harvard, Stanford and other prestigious schools and pushed Keck’s ranking in U.S. News & World Report up five spots to No. 34.

Professors were given the option of completing an anonymous online survey or writing letters. Some wrote lengthy responses filled with specific examples of Puliafito’s shortcomings and urged the administration to replace him, according to interviews.

The Times reviewed four of these evaluations.

“His presence has created a very negative atmosphere at KSOM which has alienated a large number of faculty and chairs and created a siege mentality, in which faculty and staff are constantly worried about their welfare and ability to maintain a productive environment in which to work,” one professor wrote.

‘A very low level of faculty morale’

Another longtime faculty member described the dean as “unpredictable” and “given to erratic behavior.”

“A major, overarching problem at the KSOM is that the Dean’s lack of effective and collegial leadership have resulted in a very low level of faculty morale,” the professor wrote.

A USC employee who has seen the faculty evaluations filed in 2012 said a large number were highly negative and detailed in their criticism of Puliafito. Many of the others highlighted his strengths and weaknesses. The overall feedback showed that he was a polarizing figure at the school, the employee said.

When Garrett announced in June 2012 that Nikias had rehired Puliafito, “no one could believe it,” another senior faculty member recalled.

In a letter to the faculty and staff, Garrett said she had discussed employees’ feedback with the dean, “including the matters on which some of you believe he could pay additional attention or that may require a different approach.”

“I am certain he will move forward with your suggestions firmly in mind,” she wrote.

Nikias declined to speak about the complaints made against Puliafito. Garrett left USC to become the president of Cornell University in 2015; she died last year.

Puliafito’s conduct became even more troubling in his second term.

The Times investigation published earlier this month found that the dean spent long hours partying with a group of younger addicts, prostitutes and other criminals in 2015 and 2016, and brought some to his Keck office in the middle of the night.

USC colleagues recalled that, during the same period, Puliafito was often absent during working hours.

“His staff would say, ‘I don’t know where the dean is. I will try to call his cellphone,’ ” said a university administrator who regularly had business with Puliafito.

Puliafito put on notice

In November 2015, Provost Quick put Puliafito “on notice for being disengaged from his leadership duties,” Nikias wrote in his letter to the university community Friday.

In March 2016, the dean was with a 21-year-old woman in a Pasadena hotel room when she overdosed. The woman, Sarah Warren, told The Times she and Puliafito resumed using drugs as soon as she was released from the hospital.

A witness to the overdose phoned Nikias’ office March 14 and threatened to go to the press if the school didn’t take action against the dean.

Nikias said in his Friday letter that two receptionists who spoke to the witness did not find the report credible and did not pass it on to supervisors.

Just a few days earlier, Nikias said, two university employees had come forward with separate complaints about the dean. They told Quick that Puliafito “seemed further removed from his duties and expressed concerns about his behavior.”

“The Provost consulted with me promptly and, as a result, confronted Dr. Puliafito. He chose to resign his position on March 24, 2016, and was placed on sabbatical leave,” the president wrote.

On the Keck campus, the timing of Puliafito’s resignation — on a Thursday in the middle of the school term with no advance notice — seemed suspicious.

“Everybody read it as cover story,” said one senior faculty member. But, he added, “there was a sense of relief.”

Nikias and top USC officials honored Puliafito and praised his leadership a few months later at a campus reception. He continued to practice medicine at USC clinics.

In his Friday night letter, Nikias wrote that school officials didn’t hear about the overdose until they received an “unsubstantiated tip” months after Puliafito stepped down as dean.

“When we approached Dr. Puliafito about the incident, he stated a friend’s daughter had overdosed at a Pasadena hotel and he had accompanied her to the hospital,” he wrote.

The president also said that in March, The Times did provide the university with “detailed questions about, and a copy of a 911 recording from the Pasadena hotel incident.” The recording was “immediately referred to the Hospital Medical Staff,” a committee that assesses clinical competency, Nikias said. In the 911 call, Puliafito describes himself as a doctor and the woman who had the overdose as his “girlfriend.”

The clinical competency committee “determined that there were no existing patient care complaints and no known clinical issues,” the president said.

It wasn’t until The Times published its report that the school barred Puliafito from seeing patients and the state medical board launched an investigation of him.

On Friday, USC’s crisis management firm released a letter from the chairs of 23 Keck departments. Addressed to USC’s board of trustees, it affirmed their support for Nikias and Quick.

ALSO

Steve Lopez: Yet another USC scandal requires blunt talk about money culture and values on campus

Editorial: Is USC committed to transparency, or just damage control?

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.