L.A. adds more public toilets as homeless crisis grows

Los Angeles officials have debated for decades how best to provide for one of the most basic needs of homeless people.

For those camped in the 50-block skid row district, the streets have been an open-air restroom — with only nine toilets available overnight in recent months to as many as 1,800 people camped on sidewalks.

Over the years, the city would install bathrooms and then haul them away after they were commandeered for drug use and prostitution. Some in downtown also worried the restrooms would give a permanence to the homeless camps, and argued that in the lawless atmosphere of skid row, people would not use them.

But with homelessness at crisis proportions, the first new public toilets on skid row in more than a decade opened Monday.

The action represents a new consensus among many downtown interests about how to provide the essential service on skid row. The restrooms also are expected to help in the fight against a statewide hepatitis A outbreak spread by poor hygiene in homeless camps that has killed more than a dozen people in San Diego.

The Los Angeles facilities will be decidedly different from those in the past, both aesthetically and culturally.

A key will be having full-time attendants, whom activists are calling “ambassadors,” to monitor the restrooms and make people feel welcome. Homeless advocates also hope to have a snack stand and a bench for resting and chatting with friends, as well as provide feminine hygiene products, which are in short supply on skid row.

The new approach comes as the border between skid row and the rest of downtown is shifting. High-end development is rising at skid row’s doorstep, and the tent cities that once were largely limited to skid row are spreading to other parts of the city.

“In other places, the bathrooms might be seen as something that’s going to attract certain behaviors or people,” said Downtown Los Angeles Neighborhood Council director Nate Cormier, a South Park resident. “We have so many people under those conditions, we’re all looking any way we can to turn the tide and deal with the crisis.”

The latest $450,000 facility is modest — eight toilets and six showers, operating four days a week, in a trailer on a city-owned parking lot sandwiched between two homeless housing and service agencies. In addition to attendants, the toilets will be monitored by a maintenance crew and security, which organizers hope will forestall the problems that so long soured skid row bathroom politics.

A January expansion will increase the number of showers and toilets and add laundry facilities, officials said.

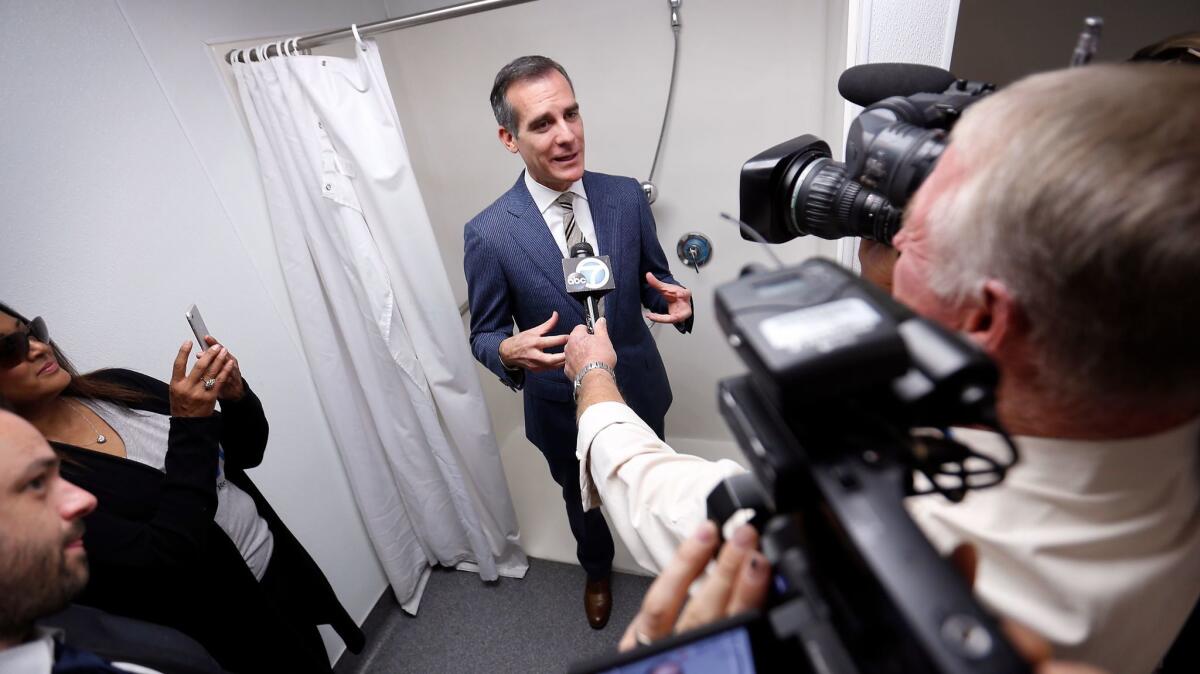

At the formal opening Monday morning, Mayor Eric Garcetti underlined the community’s role in the project.

“It is for decades that this community has cried out for the need for public restrooms,” Garcetti said at the event, which featured a bongo and guitar trio and a dozen other city and county officials. “We know here that this is one step, but it is a critical step.”

The celebratory atmosphere was broken when a skid row activist who worked on the project tore up the city certificate of appreciation that Garcetti had handed him.

“It’s 10 years late and three times short,” General Dogon, a member of the Los Angeles Community Action Network, an anti-poverty group, said as television cameras rolled. “This ain’t nothing to what we laid out and what we need.”

The mayor responded, “It’s never too late,” and promised more sanitation services, but he did not specify how many. Activists have demanded 164 toilets, spaced out within walking distance of every sidewalk camp.

Garcetti also said the project underscores the city’s rejection of its longtime “containment” policy, which centralized homeless services on skid row, and establishes a new era of partnership with activists.

“At one time, downtown L.A. was in the midst of radical revitalization and the wisdom of the day at that time was to … concentrate our problems as if somehow that would make it go away,” Garcetti said. “That has failed us.”

Skid row bathrooms were often on the front line of the city’s war on modern homelessness. In 1992, city housing officials placed dozens of portable toilets throughout skid row, only to see Mayor Tom Bradley cut off the funding.

It is for decades that this community has cried out for the need for public restrooms

— Mayor Eric Garcetti

Alice Callaghan, an activist for the poor, then arranged for six outdoor latrines festooned with ornaments and garlands for Christmas. The mayor had them hauled away.

Two years later, Bradley’s successor, Richard Riordan, had two dozen portable toilets placed on skid row. Half were yanked in 1998, then returned after a protest. But when concerns about prostitution and drug use arose in 2006, the city, with Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa in charge, had them all carted off.

The city opened a handful of self-cleaning toilet kiosks, but they were often on the blink. After county officials in 2012 and 2013 warned of an immediate public health threat , the city paid for more nighttime access to mission bathrooms and, more recently, put temporary restrooms in skid row parks.

But the county’s recommendation to add substantial numbers of toilets was largely ignored. A community audit this year found bathroom access on skid row fell short of U.N. standards for Syrian refugee camps. In April, a group called Skid Row Community Coalition came together to renew the push for new restrooms, and the mayor’s office joined in.

“This is our vision and our dream,” activist Charles Porter said Saturday. “We had people come from the tents, and they came to the meetings on time. We became our own solution.”

Even the project’s name — Skid Row Community ReFresh Spot — was important in making community members feel comfortable, Porter said.

This is our vision and our dream

— activist Charles Porter

“Who says, ‘Let’s go down to the hygiene center?’” Porter asked.

The city insisted on security, but the organizers said they made sure guards would be unarmed and from a company with a record of cultural sensitivity to skid row’s largely African American population.

“They don’t want to feel like the law is running it,” said Evans Clark, who will manage the facility. Clark also said it was important the bathrooms eventually open overnight.

“The missions open and close, and in the middle of the night, you can see somebody using the bathroom on every little corner,” Clark said.

Coalition member Tom Grode said he hoped to enlist volunteers to help run the toilets.

“The real problem with skid row is it’s been denied its rights as a community,” said Chris Mack, a longtime skid row outreach worker and a coalition member. “This space is being done with an aesthetic, and with a person’s dignity in mind.”

The facility will have to move when the Weingart Center begins building housing on the site as part of the city’s ambitious construction program, Clark said.

Though supporters see the bathrooms as a possible turning point for the beleaguered community, the benefits are limited. Cormier said the only concern he’s heard about the project was that it was a “drop in the bucket” compared with the human services needs of downtown’s homeless population.

“This spot here is temporary and certainly is not the answer to the problem of homelessness,” said Deacon Alexander, a longtime skid row resident and a restroom organizer. “It resolves one point and one point only: a place to go to the bathroom.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.