Nipsey Hussle had a plan to beat gentrification — in South L.A. and across the U.S.

L.A. Times Today airs Monday through Friday at 7 p.m. and 10 p.m. on Spectrum News 1.

Nipsey Hussle’s stretch of Slauson Avenue has largely been overlooked by the gentrification boom that has transformed so many neighborhoods of Los Angeles.

The lack of investment in the Hyde Park section of South L.A. shows on the faces of distressed buildings, some still etched with the names of bygone businesses that haunt the neighborhood like ghosts.

In the months before Hussle was gunned down in front of his clothing store in late March, the rapper was working to bring economic development to the blighted blocks around Slauson and Crenshaw Boulevard, but on his own terms. He wanted more for his community, but he wanted to the changes to be driven from within.

RELATED: Nipsey Hussle’s Slauson Avenue

At the time of his death, Hussle was reaching out to a diverse array of partners — from fellow musicians and L.A. politicians to a Republican senator from South Carolina — to make the revitalization of Hyde Park something larger and potentially longer-lasting.

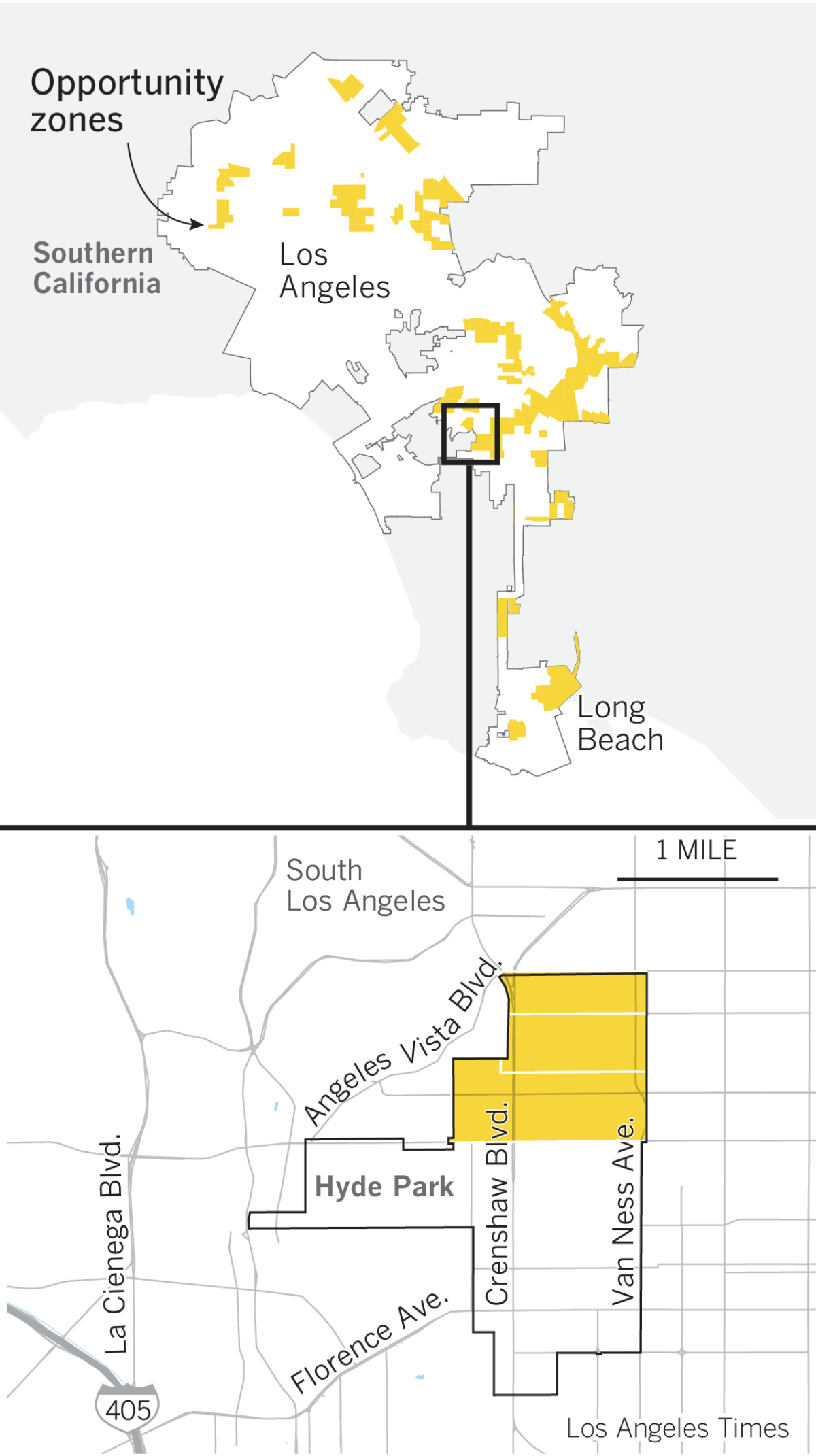

Hussle was part of an investment group that was planning to use a tax incentive carved out in a recent federal law to revive not only his neighborhood, but other forgotten, low-income communities in 11 cities, Washington, D.C. and Puerto Rico.

Celebrities and South L.A. residents alike have lauded his efforts to leverage the tools of other institutions that long ago abandoned his community. Jay-Z praised Hussle’s work in a show last month in New York’s newly renovated Webster Hall.

“Gentrify your own ’hood, before these people do it,” he rapped. “Claim eminent domain and have your people movin’. That’s a small glimpse into what Nipsey was doing.”

Together with his business partner, real estate developer David Gross, Hussle had been scheduled to meet with Sen. Tim Scott, a Republican from South Carolina, to discuss rolling out an investment fund they had created called “Our Opportunity.” Its mission is to work with the hometown heroes “of every large, majority black city to, in a systematic way, acquire and develop transformative projects,” said Gross, who grew up in South L.A.

And Hussle, an activist who has been hailed for never abandoning his ’hood even after earning a Grammy nomination, had also derived a way to have residents invest alongside him. The plan was to crowdfund from each community and give residents an ownership stake in every project created in their neighborhood.

“He wanted to be a symbol and really spark a movement,” Gross said of Hussle, born Ermias Asghedom. “Basically, it was the economic version of Black Lives Matter. [That] is what we were trying to create.”

The tax incentive that Gross and Hussle were planning to tap was promoted by Scott and included in President Trump’s 2017 overhaul of the federal tax code. It offers potentially large tax breaks to investors who are willing to pour much needed capital into rebuilding poor and sometimes up-and-coming communities that have been designated as “opportunity zones.”

Investors can take proceeds that would normally be subjected to hefty capital gains taxes — such as those from the sale of a business, stocks or an investment property — and put them into an opportunity zone investment fund to defer and potentially reduce those taxes. To see the full tax benefit, the funds must be invested for a decade.

When Trump signed an executive order in December to establish the White House Opportunity and Revitalization Council, he said that opportunity zones would “deliver jobs, investment and growth to the communities that need it the most.” Federal and local officials say they hope this kind of long-term injection of private-sector capital will uplift poorer communities that have not recovered from the Great Recession of the late 2000s.

The tax incentive has already grabbed the attention of Wall Street and some wealthy families. So far, more than 100 opportunity zone funds have been set up nationwide, with the goal of raising $24 billion that would be funneled into housing projects and businesses, according to the National Council of State Housing Agencies.

But since the 8,700 opportunity zones were identified by governors and designated by the federal government last year, there has been much debate over whether certain communities on the list truly qualify as economically disadvantaged. Some neighborhoods in Oakland and Queens, New York — both of which have seen a flood of capital and development in recent years — landed on the list. As did Hollywood.

And there’s some concern that the infusion of cash and type of projects such investment could bring might spur gentrification and displacement in neighborhoods that are legitimately struggling — the very thing that Hussle was trying to fend off in his own area of South L.A. Critics fear developers will prize profits over people.

Last year, more than 30 community groups sent a letter to then-Gov. Jerry Brown, urging him to slow down his process of selecting federal census tracts to be designated opportunity zones.

“There are no guardrails around the kind of investments that can qualify for this preferential tax treatment,” said Kevin Stein, deputy director of California Reinvestment Coalition, a housing advocacy group. “A main concern of ours is that this kind of unrestrained investment in certain neighborhoods that are already feeling gentrification pressures — it will just be fuel on that fire and could result in large scale displacement of low-income people and people of color.”

John Lettieri, president and CEO of the Economic Innovation Group, part of a coalition that successfully lobbied Congress to create opportunity zones as part of the tax overhaul, acknowledged those concerns. That’s why, he said, it’s important that local governments and community groups draft strategies to protect residents.

Lettieri has worked with Gross in the coalition, and it was Gross who shared the plans that he and Hussle had for South L.A. and other communities across the country.

“We were excited about what they were pulling together,” Lettieri said. “I think we can see that happening on a national scale thanks to opportunity zones.”

Hussle’s business acumen was born on the streets of South L.A.

At 11, he polished shoes for $2.50 at Chambers On Slauson to pay for school clothes, he said in interviews. His goal, ambitious even then, was to shine a hundred shoes a day.

That entrepreneurial spirit earned him his nickname. Hussle said in interviews that he used to run errands for the local hustlers, some of them members of the notorious Rollin’ 60s — a street gang that he would go on to embrace in his music, while also encouraging peace.

After a trip to his father’s homeland of Eritrea, he shifted his energy away from the streets and into his music. He formed a record label called All Money In.

Hussle treated his mixtapes like collector’s items. His music was free to stream online but he priced physical copies of his 2013 “Crenshaw” mixtape at $100. Music mogul Jay-Z bought 100 copies. And he marked up his 2015 follow-up, “Mailbox Money,” to $1,000 each. He sold 60 in the first week.

Hussle sold some of his early work out of the trunk of his car in the parking lot of 3416 W. Slauson Avenue. He and Gross would later go on to pay $2.5 million to purchase the building on that lot — the same building where Hussle had opened his store, the Marathon Clothing, and the same lot where he was shot to death on March 31 over what police say was a personal grudge.

Meanwhile, the neighborhood around 33-year-old Hussle was slowly changing.

Anticipation of the $2 billion Crenshaw Metro rail line, steps from his shop, has driven up home prices nearby and pushed out some long time residents and black-owned small businesses. So, in the last years of his life, Hussle worked to cement African Americans’ place by partnering with city officials and community members to create the Destination Crenshaw art project.

Then he got to work bringing his community the sort of amenities they want and which are common north of the 10 Freeway — boutiques, grocery stores and safe play spaces.

Three years ago, Hussle set out to start an inner-city investment fund with his business partner Gross, whom he met at a Lakers game several years ago and bonded with over tequila. One of their first projects was Vector 90, a co-working space and STEM center. It’s in an industrial stretch of South L.A. that people said was too rough for that kind of investment, Gross said. It has been successful.

The duo expanded their plan after Hussle’s Hyde Park neighborhood was designated as an opportunity zone. Gross and Hussle spent the last months of the rapper’s life meeting with lawmakers and investors to discuss their fund, “Our Opportunity.”

“I was excited when I learned of his interest in Opportunity Zones,” Sen. Scott said in a written statement. “And I’m saddened that we will never get to discuss our plans and vision for what this initiative could do to partner with and strengthen Nipsey’s already amazing efforts.”

Hussle and Gross wanted to build on the L-shape strip mall — home of the Marathon Clothing — which they bought in January. They were going to add 80 units of apartments and condos on top of shops with healthy food options. Like with the larger investment fund, the duo wanted to make their neighbors their business partners. They were going to set aside 20% of the housing units for residents of the neighborhood, and invest with them so they could own their homes, Gross said.

Gross said he and the other investors plan to unveil the “Our Opportunity” fund later this month.

California Deputy Treasurer Jovan Agee said Hussle provided a blueprint to building wealth that can serve as an inspiration to the everyday man who might be working the graveyard shift and selling T-shirts on the side.

“He really had to scratch and scrape to get into a position of acknowledgement,” he said. “What he did is a blue-collared approach to economic development and self-wealth building that others can replicate.”

For more California breaking news, follow @AngelJennings. She can also be reached at [email protected].

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.