Why some buildings crumbled and others survived the Mexico City quake: A sober lesson for California

A building that survived the last earthquake will not necessarily survive the next one. (Sept. 21, 2017)

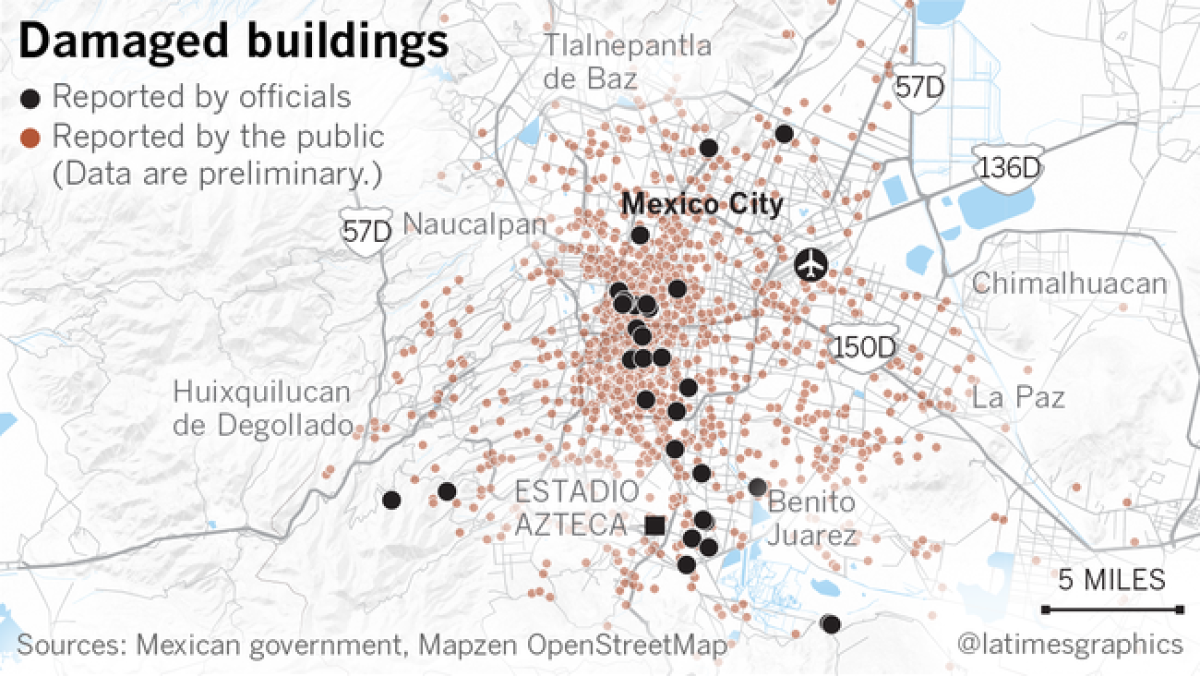

The amateur videos emerging from the magnitude 7.1 earthquake that devastated Mexico City on Tuesday are grim. Some show taller buildings swaying. Others show short, squat structures suddenly collapsing. Remains of brick walls have fallen onto sidewalks in heaps of rubble.

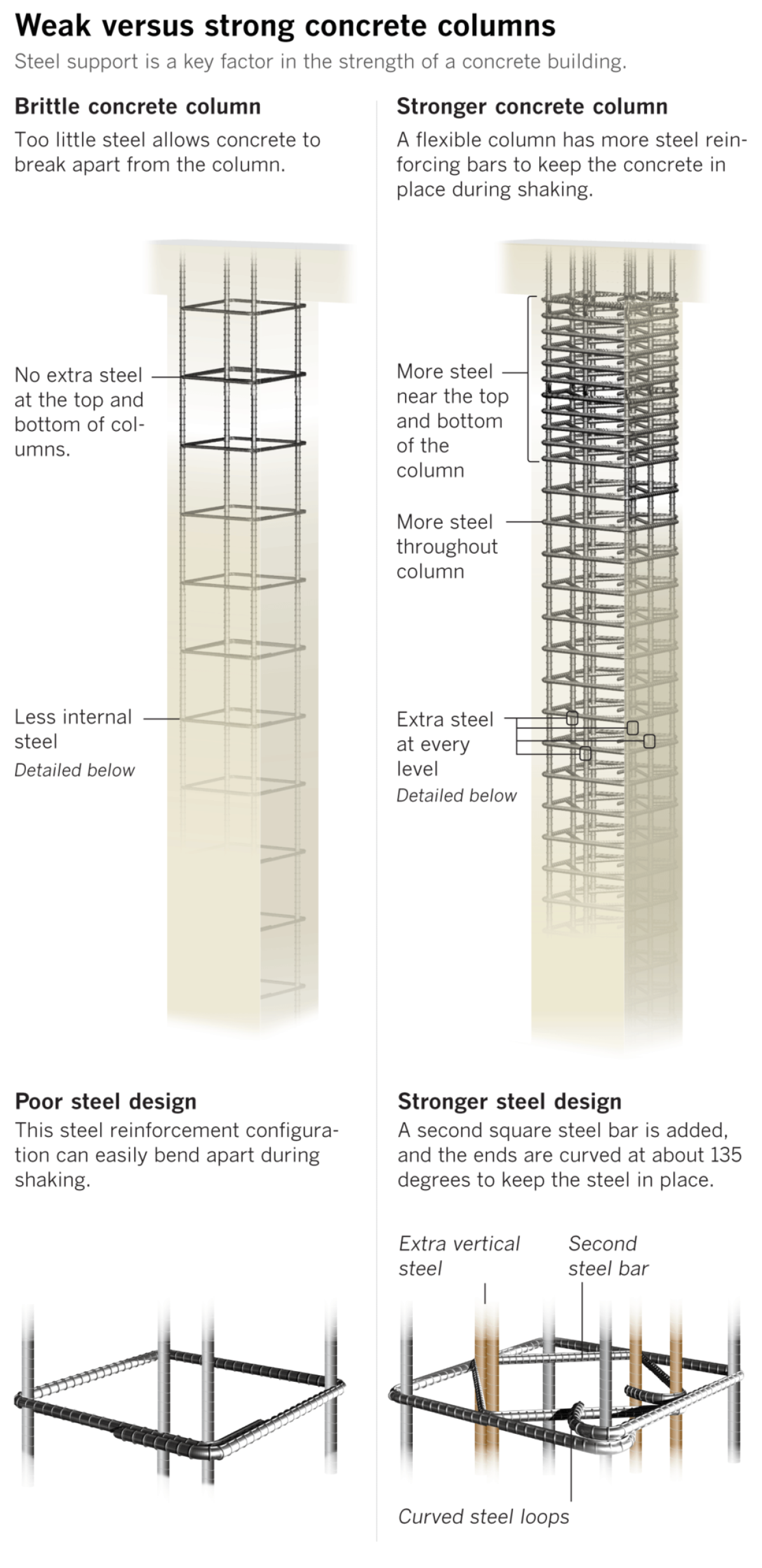

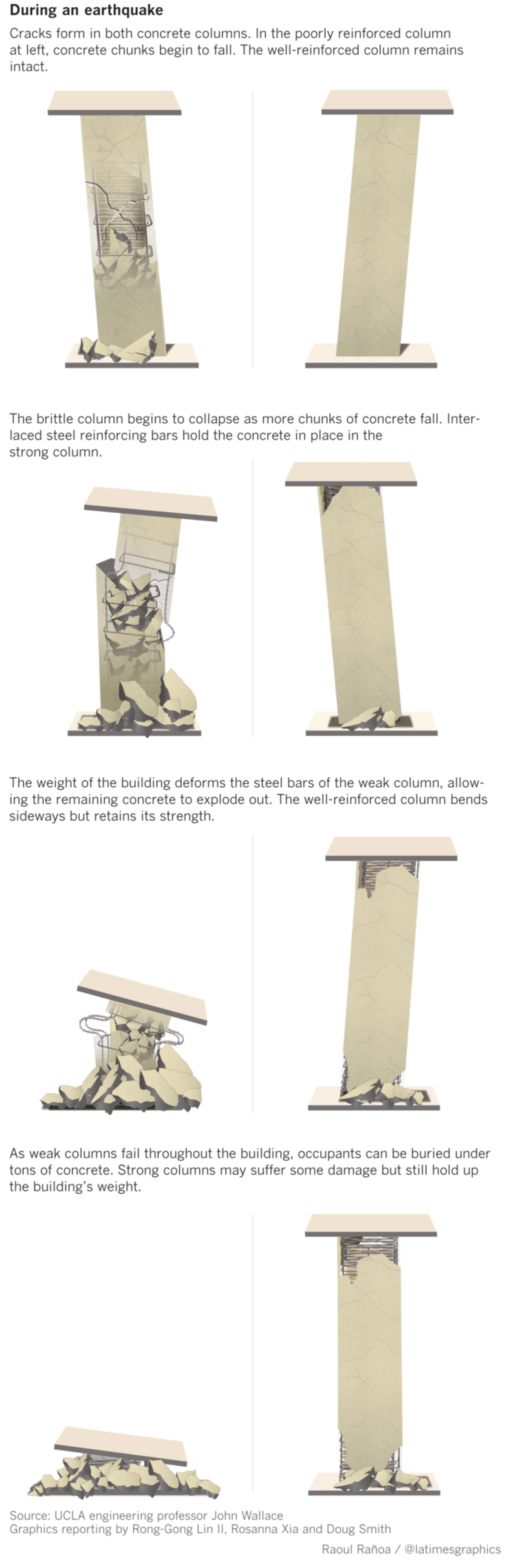

Over decades, seismologists and structural engineers have gained extensive knowledge about why some buildings collapse while others remain standing during an earthquake. Part of the answer lies with construction: Concrete buildings without enough steel reinforcement can become disastrously brittle during shaking, allowing concrete to burst out of the columns just before a catastrophic collapse.

But buildings can either survive or fail based on the vagaries of geology, geography and physics.

In Tuesday’s quake in Mexico, preliminary reports suggest that shorter buildings were especially susceptible to collapse, including older structures that had survived the nation’s 1985 magnitude 8 earthquake that killed an estimated 10,000 people. Meanwhile, unlike the ’85 quake, Mexico City’s taller buildings appeared to ride out the latest temblor in better shape.

Seismology and engineering experts say because Tuesday’s calamity hit far closer to Mexico’s capital — 80 miles away compared with 250 miles in the 1985 quake — shorter buildings were far more vulnerable than they were during the earthquake that struck a generation ago.

The reports illustrate a fact of seismology: Short buildings are especially at risk when big earthquakes strike nearby. They actually can avoid major damage if the structures are farther away from the origin of megaquakes.

Taller buildings, meanwhile, are especially threatened by megaquakes, even if the temblors originate from a significant distance.

Experts say the lessons are clear for California and underscore an ominous warning: Just because your home or workplace survived a previous earthquake doesn’t mean it will endure the next one.

‘A false sense of security’

Surviving one quake doesn’t mean a building is safe

“I hear quite often, ‘Hey, we went through the 1994 Northridge earthquake. We’re OK.’ Well, that’s a false sense of security,” said Kit Miyamoto, a member of the California Seismic Safety Commission and chief executive officer of Miyamoto International, a global structural engineering firm. “This earthquake proved it: Doing well in one earthquake doesn’t mean you’ll do well in the next earthquake — because every earthquake is different, and every building responds differently.”

In certain respects, Los Angeles has yet to face what Mexico City has endured.

Despite several devastating quakes — in 1933 in Long Beach, 1971 in Sylmar and 1994 in Northridge — many vulnerable buildings constructed during Southern California’s rapid expansion in the 20th century simply have not had to face the intense shaking that scientists know can happen during an earthquake.

The last magnitude 7.8 quake that struck Southern California hit in 1857, long before the modern era of Los Angeles.

“We’re a lot closer to the San Andreas than Mexico City is to their subduction zone [the closest region to the capital capable of producing magnitude 8 earthquakes],” seismologist Lucy Jones said.

Get ready for a major quake. What to do before — and during — a big one »

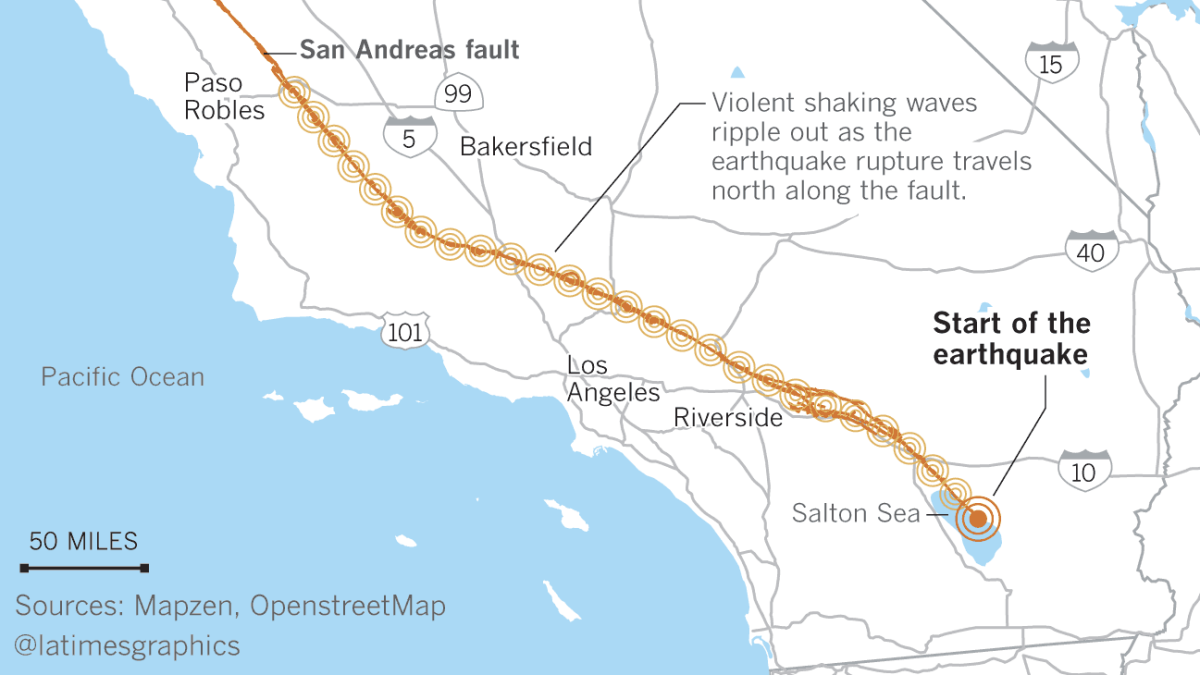

At its closest point, the San Andreas Fault is just 30 miles away from downtown L.A. That closeness means the tallest skyscrapers in the nation’s second-largest city could be quite vulnerable during a megaquake.

A U.S. Geological Survey simulation coauthored by Jones and published in 2008 said it was plausible that five steel high-rise buildings throughout Southern California — whether in downtown L.A., Orange County or San Bernardino — could come tumbling down should a magnitude 7.8 earthquake strike the San Andreas.

California could be hit by an 8.2 mega-earthquake, and it would be catastrophic »

After the 1994 Northridge earthquake, a flaw was discovered in a common type of steel building that showed how the frame can fracture in an earthquake; Los Angeles and most other cities in California have not passed laws requiring retrofits to repair this design flaw. (Santa Monica and West Hollywood recently adopted new retrofit laws for this type of building.)

“We don’t really know what’s going to happen to those really tall buildings. We’ve never put them through a really big earthquake,” Jones said.

By contrast, Mexico City is so far away from a fault zone capable of magnitude 8 earthquakes that its tallest buildings are relatively safe, Jones said. In that country’s 1985 earthquake, buildings that were five to 20 stories tall suffered major damage, Jones said, while shorter buildings generally performed better.

Downtown L.A.’s shortest buildings also haven’t been tested with extreme shaking, Jones said. At no point in modern history has downtown Los Angeles endured the kind of intense shaking that the San Fernando Valley did during the 1994 Northridge earthquake.

“Your Northridge-type earthquake is about as bad as it gets for small buildings like a single-family house or a small apartment complex,” Jones said. But while places like Northridge and Chatsworth have endured what is close to the worst-case shaking, places a bit farther away — like Pasadena, Hollywood and downtown L.A. — have not.

“Even Santa Monica” has not, she said, despite the intensity of damage in that coastal city during the ’94 quake, Jones said. “The reason there was so much damage there was because of how old the buildings are.”

A Matter of Geology and Physics

Why small and tall buildings can react differently in the same earthquake

Why shorter and taller buildings can react differently during the same earthquake is a matter of geology and physics — similar to how a wineglass can survive some musical notes, but the right one can cause it to shatter.

Megaquakes, like 1985’s magnitude 8 in Mexico, are caused by extremely long faults and produce low, booming shaking frequencies that can travel for vast distances — think of the bass beat you might hear from a distant rave. They also produce the sensation of rolling motion, like the kind you might feel on a boat. Long objects, such as tall buildings, are particularly vulnerable to this kind of rolling, shaking motion.

Even worse, Mexico City sits on an ancient lake bed with soft soils that amplify the shaking from an earthquake by 100 times, Jones said. The lake bed is believed to have a natural resonant frequency that makes buildings that are five to 20 stories tall particularly vulnerable — and that’s why those buildings suffered the most destruction in the 1985 earthquake, Jones said.

Something similar happened in the 2015 magnitude 7.8 Nepal earthquake, in which Kathmandu, which also sits on an ancient lake bed, saw its tall buildings damaged while its shorter structures held up far better, Miyamoto said.

By contrast, short buildings are most vulnerable when they are close to the shaking source — where the experience can be described as herky-jerky or having sudden, intense up-and-down or side-to-side movement. But such high-frequency shaking is felt only close to an earthquake’s source.

Because the 1985 earthquake struck 250 miles away from Mexico City, such high-frequency motion faded by the time the shaking arrived in the capital city. As a result, short buildings escaped major damage and were able to survive until a closer earthquake struck, as it did on Tuesday.

How Different Quakes Would Affect L.A.

A magnitude 7 in Hollywood would damage different buildings than an 8 on the San Andreas

In the Los Angeles area, a sharp magnitude 7 earthquake on an urban fault that runs through the metropolitan region — such as the Newport-Inglewood, Whittier or Sierra Madre faults — will test short buildings like no other earthquake in the modern era, Jones said. Meanwhile, a magnitude 8 on the San Andreas Fault likely will spare the worst from striking single-family homes in places farther away from the fault, including the L.A. Basin. But the same megaquake could result in “collapses of high-rises at relatively large distances from the fault,” Jones said.

Los Angeles does have one advantage over Mexico City in terms of earthquake risk: While the L.A. Basin also is made of soft soils that amplify an earthquake’s shaking, it does so only by a factor of 5, compared with Mexico City’s factor of 100, Jones said.

A Concrete Risk

Why brittle concrete buildings collapse

Miyamoto said the types of buildings that have collapsed in Mexico City are what structural engineers would expect: brick structures as well as brittle concrete buildings, especially those with weak first floors. Photos of many of the collapsed structures are made of brittle concrete, Miyamoto said.

A dramatic amateur video, which circulated widely on social media and was shown on Telemundo and NBC, depicts a five-story concrete building that initially wobbles from the earthquake. However, the ground-floor columns keeping the building upright appear stressed, and chunks of concrete begin to fall off the edges of the columns, weakening the building’s critical supports.

Moments later, the concrete columns appear to bend like a knee. The building suddenly collapses, and the upper floors can be seen sinking into a cloud of dust as onlookers start running.

“¡Dios mío! ¡Dios mío!” a woman can be heard saying. “My God! My God!”

Miyamoto said the collapse is a textbook example of what engineers would expect of a brittle concrete building, in which a failure to use enough steel rebar in the columns allows concrete to burst outward during an earthquake, prompting a disintegration of the column and the collapse of the building.

This design flaw is common in older buildings worldwide, including in the United States.

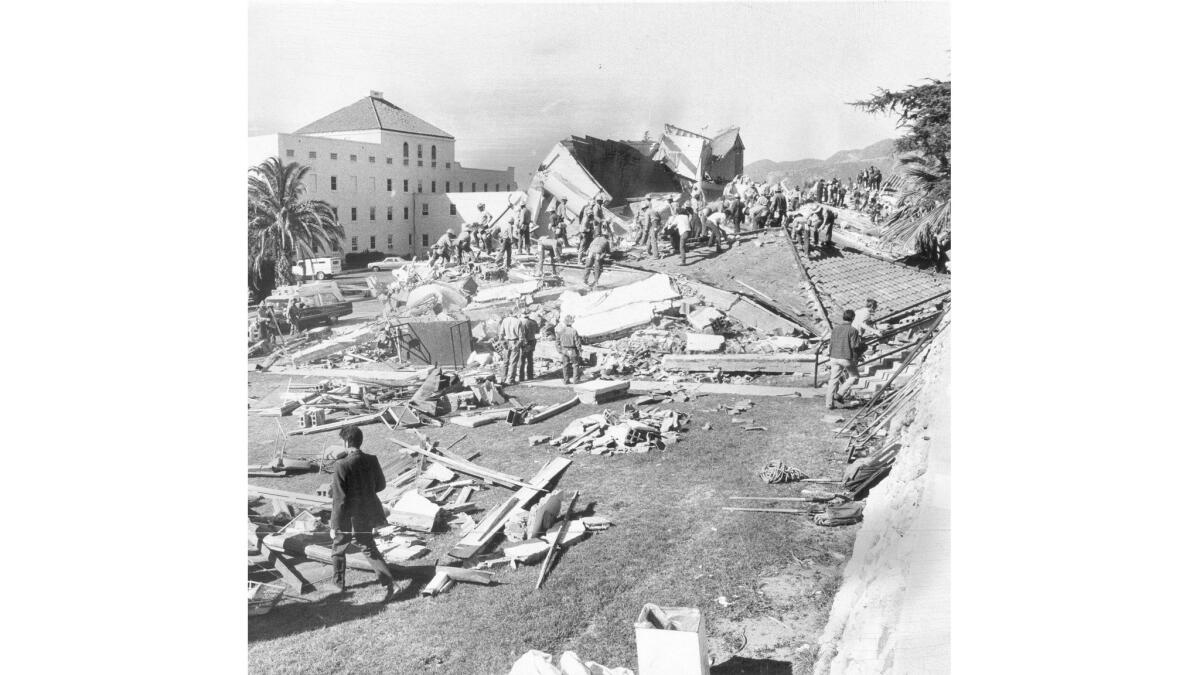

The defect gained considerable attention after the 1971 Sylmar earthquake caused the collapse of the newly constructed Olive View Medical Center.

Several other concrete structures came tumbling down in that earthquake, in which 52 people were killed.

Brittle concrete buildings also collapsed in the 1994 Northridge earthquake, including a Bullock’s department store and Kaiser Permanente medical office.

The destruction of two of these brittle concrete buildings in an earthquake in New Zealand in 2011 caused the death of 133 people.

There are an estimated 1,500 brittle concrete buildings in Los Angeles. Following a Los Angeles Times report on the problem of such structures in 2013, L.A.’s elected leaders in 2015 decided to require owners to retrofit those buildings, setting a 25-year deadline to strengthen such buildings once they are given an order to seismically evaluate them.

Most other cities in California do not require retrofit of those types of structures; Santa Monica and West Hollywood, however, recently adopted new laws to require strengthening of this building type.

Miyamoto said Los Angeles should accelerate the deadline to retrofit its concrete buildings.

“We should go faster,” he said. “The earthquake will not wait for us.”

In Mexico City, there was a common feeling that if a building survived the 1985 earthquake, they were not vulnerable to the next earthquake, said Guillermo Lozano, humanitarian and emergency affairs director for World Vision Mexico, a Christian humanitarian organization.

“The new buildings—most of the new buildings, they were not affected. They’re OK. They had good protocols,” Lozano said. “We learned a lot from 1985, that’s true. We made very important changes in the construction rules.

“But what about the old buildings?”

Twitter: @ronlin

ALSO

Fearing a big earthquake like the one in Mexico isn't enough. Here's how to turn anxiety into action

Could your building collapse in a major L.A. earthquake? Look up your address on these databases

Watch: Here's what it looked like during and after the Mexico earthquake

UPDATES:

12 a.m., Sept. 21, 2017: This article was updated with a quote from Guillermo Lozano, the humanitarian and emergency affairs director for World Vision Mexico, and reflects the recent action by West Hollywood to pass ordinances requiring retrofits of steel and concrete buildings.

This article was originally published at 12:45 p.m. on Sept. 20, 2017.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.