Among Vietnamese, a generational divide arises in fight against deportation threat

In his 85 years, Lan Hoang has many times seen and heard about the power of communism to stir passions on the streets of Little Saigon.

There was the time a video store owner displayed the flag of communist Vietnam and an image of Ho Chi Minh, causing thousands of angry residents to protest. Ten years ago, hundreds of people hoisting signs gathered outside a Westminster newspaper that published a photo of a foot spa bearing the colors and stripes of the anti-communist South Vietnamese flag, calling it a desecration.

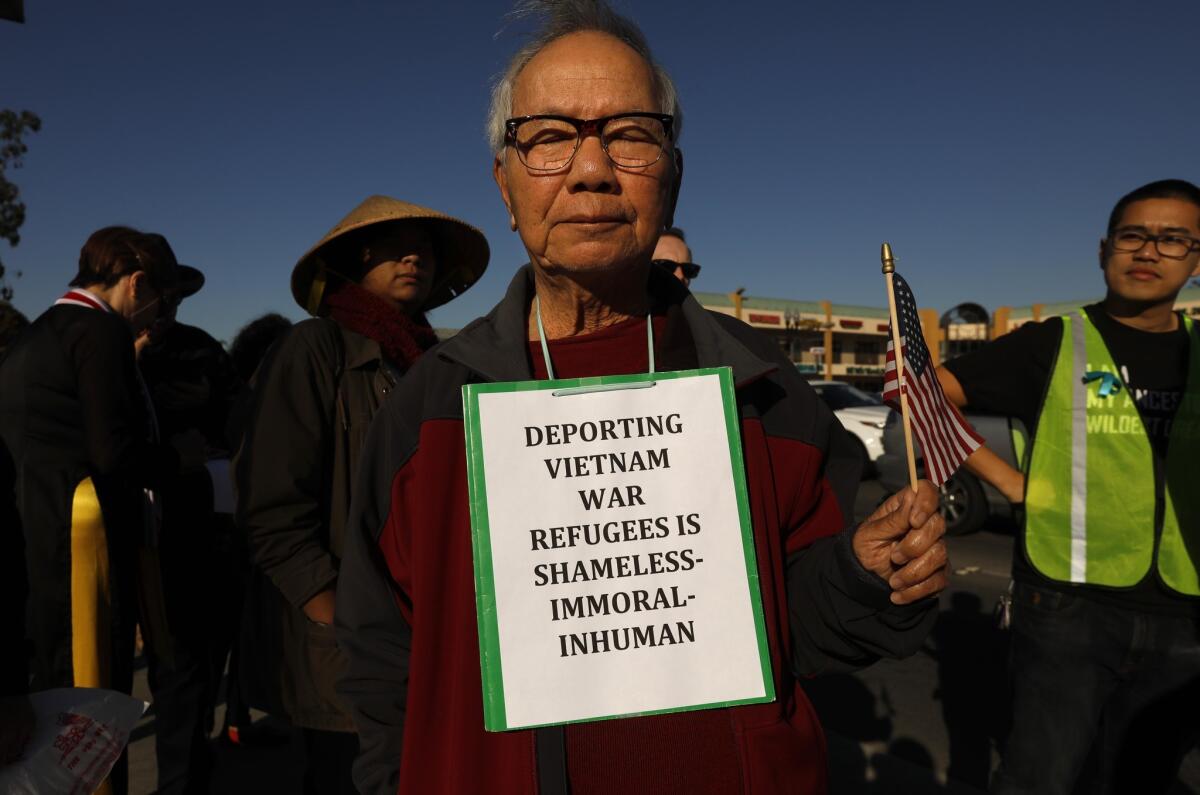

But when Hoang turned up to a protest in the neighborhood against the Trump administration’s recent threats to deport Vietnamese immigrants with criminal convictions back to their homeland, he was surprised by the apparently tepid response by older immigrants. Usually the most fervently anti-communist, only a handful showed up.

“Everyone was shouting and I looked around, wondering, ‘Where are the people my age?’ ” said the retired records clerk from Santa Ana, who said he was shocked by the White House’s move. “It’s so inspiring to see the youth taking action. They are well-educated, well-organized. I only wish that the others who have been visible for many years were here to support them.”

After word spread about a renewed push by the Department of Homeland Security to get Vietnam to accept more deportees, some people saw it as a mistake by the Trump administration given the GOP’s fading strength in Orange County and the historical support that the Republican Party has gotten from Vietnamese Americans.

But in a community where many older residents oppose undocumented immigration and younger ones tend to lean left politically, the controversy is just the latest to underscore the generational divide among those of Vietnamese descent.

“So many of our lives are in limbo. And do we get any support from our own community? Very little if you’re talking about the elders. What happened to all the voices speaking out for anti-communism? Why haven’t they mobilized?” said Tung Nguyen, 40, a Santa Ana activist who has served time in prison and helped lead protests in Little Saigon. “If they really care about human rights violations, well, violations are happening, not just in Vietnam but right here in our backyard.”

Earlier this month, Trump administration officials met with their counterparts from Hanoi to talk about a pact the two countries signed in 2008, under President George W. Bush, that protected the Vietnamese who came to the U.S. before July 12, 1995, from deportation.

More than 8,000 Vietnamese residents in the U.S. who escaped their homeland but later committed crimes — even minor ones for which they have served time — would be at risk of deportation if officials succeed in changing the agreement. Overall, since 1998, more than 9,000 Vietnamese immigrants have received a final order of removal, according to the Southeast Asia Resource Action Center.

Kim Bui, a 19-year-old sales clerk at an Anaheim snack shop, said members of her parents’ generation and older tend to be “no-shows” when the topic is immigration and deportations.

“I think these issues have a stigma to them. The older people are heavily Republican and they’re very focused on traditional values,” said Bui, who grew up in Orange County. “They are happy to talk about injustice in their homeland and they want to stay in that box, without making waves about U.S. politics.”

On social media and in the mainstream press, some young advocates for the emerging anti-deportation movement say they’ve long pushed for fairness and equality, and that Vietnamese Americans have shown up for other immigrant groups throughout U.S. history.

Still, within their own group, what’s missing is the “leadership of the older generation,” said Nguyen.

“We understand if they’re ashamed of some of us for our mistakes and our arrests,” he said, referring to immigrants with criminal records. “But do they need to punish our wives and children? Why would they not come out and fight for us so families can stay together? Why separate people who have paid the price for their bad choices or who will be exploited in Vietnam?”

Until last month, Nguyen was at risk for being deported to Vietnam. In 1996, he had been sentenced to life in prison for not intervening while one of his buddies stabbed a man to death. In 2011, Gov. Jerry Brown allowed him an early release, recognizing his bravery for saving dozens of civilians in a prison riot. Brown then gave Nguyen a full pardon this past Thanksgiving.

Last year, the Trump administration started pursuing the removal of a number of long-term residents from Vietnam and Cambodia, and to a lesser extent, Laotians, some of whom arrived in the United States decades ago as refugees, according to immigrant rights advocates and lawyers who have sued to halt the push. The administration maintains many have criminal records that subject them to deportation.

“It’s a priority of this administration to remove criminal aliens to their home country,” Katie Waldman, a spokeswoman for the Department of Homeland Security, told The Times.

The latest available numbers on removals by Immigration and Customs Enforcement paint a mixed picture. In fiscal 2016, which ended in September 2016 toward the end of the Obama administration, officials removed 35 Vietnamese people. In fiscal 2017, including the first nine months of the Trump administration, officials removed more than double that number: 71.

Removals of Cambodians and Laotians have been relatively minimal: In fiscal 2016, the agency removed 74 Cambodians; the next year, it removed only 29. The agency removed zero Laotians in fiscal 2016, and five the following year.

But critics see the moves as yet another example of how, far from the U.S.-Mexico border, in both rhetoric and action, the Trump administration is signaling that no immigrant, whatever their legal status, is safe.

“They are going to come for our Vietnamese brothers and sisters,” Tung Nguyen said. “Mr. Trump has made it clear that immigrants are his top target — and that immigrants with criminal records are the priority.”

That approach is a decided shift from nearly 45 years ago, when the United States sponsored the evacuation of roughly 125,000 Vietnamese refugees after the fall of Saigon signaled the end of the Vietnam War. The humanitarian crisis precipitated in the Southeast Asian countries of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, devastated by U.S. bombing campaigns and conflict, ultimately brought more than a million refugees and immigrants to U.S. shores.

The U.S. Cambodian and Laotian immigrant populations more than tripled from 1980 to 2017, and the Vietnamese immigrant population exploded from about 230,000 in 1980 to more than 1.34 million in 2017, making them the sixth-largest foreign-born group in the United States, according to the Migration Policy Center, a nonpartisan research institute.

About two in five Vietnamese immigrants reside in California, with Orange County, Santa Clara County, and Los Angeles County making up three of their top four destinations nationwide, census data shows.

To help shape the anti-deportation movement, grassroots groups such as Viet Unity, VietRise, along with APIROC, or Asian & Pacific Islanders Re-Entry of Orange County, founded by Tung Nguyen with a mission to reintegrate incarcerated people, are mobilizing online to boost awareness nationwide.

Julie Vo, a member of VietUnity — SoCal, said her organization is coordinating with the National Vietnamese Anti-Deportation Network and the Southeast Asian Deportation Defense Network. “This is not just a Vietnamese or Southeast Asian issue — but impacts all communities of color. Our struggles are tied to one another,” she said.

But these efforts haven’t swayed as many older Vietnamese.

After escaping Vietnam, Am Nguyen, 70, lived in Philippine refugee camps, struggling for eight months, before resettling in California in 1981. She had given birth to her fourth child while housed in the Palawan Island barracks, clinging to hope that officials would allow her family passage to the U.S.

“To be welcomed to America is a privilege,” the Westminster grandmother said. “Once you’re here, you need to follow the rules here. If you violate something that is very serious, you should be deported. They have the right to send you back.”

Nguyen and her South Vietnamese Army veteran husband Hoa Dang, 76, both Republicans, said they are against illegal immigration and support keeping a close watch on the borders “because with terrorism, you have to be careful since you never know who’s going in and out.”

Twitter: @newsterrier

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.