In a violent year in San Bernardino, unsolved homicides leave families grasping for answers

With San Bernardino enduring a record year of deadly violence in 2016, homicide detectives sometimes struggled to keep up.

They were teenagers in love. Ariel Bojorquez, 19, had graduated from high school and was talking about joining the Army. His girlfriend, Rosa Isela Chavez, 17, was months away from finishing her senior year.

They were driving on a sunny April afternoon through a tidy west San Bernardino neighborhood when a white sedan pulled up next to them and someone inside began shooting, hitting them both and sending Bojorquez’s Honda crashing into a yard.

Bojorquez died there. Chavez died at a hospital.

Unlike many shootings in San Bernardino, which in 2016 had one of its most violent years in decades, the deaths of Bojorquez and Chavez didn’t appear to be gang-related, police said. Nor did they appear to be connected to any other recent slayings.

The two of them were “just gone out of nowhere,” said Evelyn Bojorquez, Ariel’s sister.

Police asked the community for help, releasing surveillance video that showed the suspect’s car driving alongside Bojorquez’s Honda and speeding away.

But more than eight months later, what happened to the couple is still a mystery.

There were 62 slayings in San Bernardino in 2016 — a 41% increase from the year before. It was the deadliest year in the city since 1995.

The violence is an open wound on a city trying to recover from a prolonged bankruptcy and the 2015 terror attack. And it didn’t abate for the holidays — five people were shot and wounded on Christmas Day. One was killed the morning after.

Amid this violent surge, San Bernardino police have at times struggled to find the killers, leaving mothers, fathers, siblings and children grappling with unanswered questions.

The case of 12-year-old Jason Spears, who was killed walking to buy chips at a convenience store in March, remains unsolved.

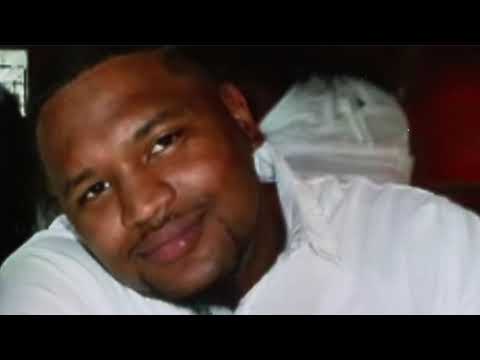

So does that of Kevin Jones, 27, the father of a 4-year-old boy, who was shot to death while standing outside an apartment complex with friends four days before Jason died.

The case of Jose De La Torre, 24, who was found in his car trunk in August, also is unsolved, as is that of John Black, 37, who died on Jan. 2, 2016, marking the city’s first homicide of last year.

Arrests have been made or warrants have been issued in about 44% of 2016’s homicides, police say.

While that rate is better than some places — the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department solved about 32% of homicides in its jurisdiction last year — it is lower than many others. Nationally, nearly two-thirds of all homicides are solved, while the most successful departments can solve about 80% to 90% of slayings, experts say.

The rate at which murder cases are solved is affected by numerous factors, particularly how departments prioritize and allocate resources.

But San Bernardino’s detective bureau, like much of the bankrupt city, has been cut back significantly.

In 2012, the bureau had 44 full-time detectives. It now has 27, said Lt. Mike Madden, a department spokesman. Ten of those detectives investigate homicides, though they also investigate non-fatal shootings and other assaults with a deadly weapon, of which there were hundreds this year.

The city, which should emerge soon from bankruptcy, plans to increase police staffing and recently was awarded a federal grant to help with that, but the hiring process is slow.

Like police in other cities with many gang- and drug-related crimes, San Bernardino detectives also struggle with mistrust in communities, which can hamper investigations.

Often people fear retaliation for talking to the police, officers say. Others, who live by a street code, expect to take justice into their own hands.

Madden said police also are challenged by a broader sense of “distrust and discontent with law enforcement,” which he linked to the national debate on policing in the wake of high-profile officer-involved shootings.

“We have experienced cases where profanities will be shouted at our officers and our detectives who are trying to secure that scene and investigate that scene,” Madden said. “We’ve even had incidents where rocks and bottles have been thrown at our detectives.”

Charles F. Wellford, a criminology professor emeritus at the University of Maryland, said police must work to build trust with the community in order for people to cooperate with investigations — but that can be challenging when crimes aren’t being solved.

“Most people, regardless of where they live in a community, think homicide is a pretty bad thing,” Wellford said. “If they’re not cooperating, part of the reason may well be because you’re not solving a lot of your homicides. It’s kind of a chicken and egg thing. … Some of that is marketing, for the police to say, ‘We care.’ The bigger part of it is solving those crimes.”

Families who live with unsolved cases say they are haunted by the unknown.

Catherine Howard, 42, has heard numerous, irreconcilable stories about how her oldest son, Kevin Jones, was shot to death in front of a San Bernardino apartment complex on a Wednesday night in March.

Jones wasn’t alone when he was killed, and there were numerous witnesses, his family said. But Howard and Jones’ fiancée, Latoya Ware, believe those witnesses haven’t been forthcoming.

In one story they were told, Jones went to the store and got into an argument with two men. The men followed him back to his cousin’s apartment complex and the argument escalated into a fight. Then, one man pulled out a gun and shot him.

In another, Jones confronted some men he thought looked suspicious outside his cousin’s apartment. Again, the argument escalated into a fight, and one man pulled out a gun and fired.

In yet another, Jones was gambling, lost money and began arguing with the men he had been playing with. The men left, then returned and shot up the block where Jones and his friends were gathered.

His family says they don’t know what to believe.

“There was what, four, five guys with him?” Ware said. “Those four guys should know exactly what happened. Why don’t we have a story?”

Howard was a teenager when Jones was born. He was taken from her at a young age and raised for some years by his father’s family. But they reunited when he was a teenager and became close.

Now, she says, she can’t sleep thinking about what happened to her son.

She takes sedatives to keep from feeling overwhelmed, she said. When she does manage to sleep for a couple of hours, she has nightmares in which she sees a man, whose face she can’t decipher, shooting at her son.

“I feel like I’m dying a little bit more every day without him,” she said. “We don’t have nothing but memories and pictures and the thought of: When is somebody going to pay for his murder?”

Ariel Bojorquez’s family doesn’t have any versions of what led to his death. All they know is that he and his girlfriend were driving, someone opened fire and they were gone.

“They were not in gangs or anything. That’s why it’s so difficult for us to think, why or who?” Evelyn Bojorquez said.

Someone knows what happened to her brother and his girlfriend, she said. She urged them to come forward, even if it means breaking a code of silence.

“I know it’s hard. I know people are scared,” Bojorquez said. “But is there any way in your heart you could come forward?

“It’s not fair,” she added. “The way they were just killed, cold-blooded. It’s not fair.”

Twitter: @palomaesquivel

ALSO

Cops are going undercover and watching social media to combat hate crimes

The fine line for police between a ‘hate crime’ and a ‘hate incident’

Violent crime in L.A. jumps for third straight year as police deal with gang, homeless issues

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.