‘I want to cry. I’m in book heaven.’ How one reading advocate hopes to change the lives of juvenile hall detainees through a library

On one wall of her small classroom at Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall, Zoila Gallegos had set up a makeshift library, but it was never enough.

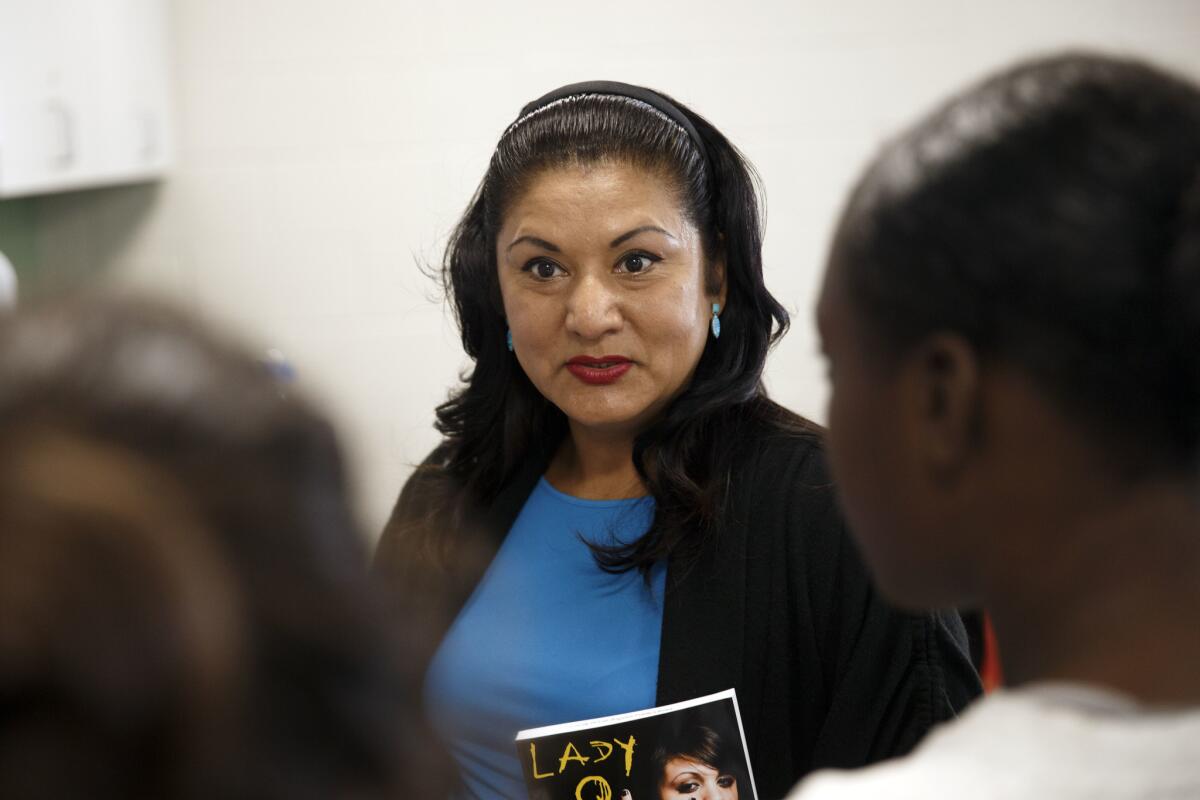

Gallegos, a reading specialist with the Los Angeles County Office of Education, has worked at the juvenile lockup in Downey for the past nine years. A child of immigrants who grew up in South Los Angeles, she struggled with English and reading and with the poverty and violence in her neighborhood. She was the first in her family to graduate from high school.

Now, Gallegos said, she makes it a mission to extend the same opportunity to the struggling readers she teaches in the juvenile hall.

“In my own way, I’m doing my own civil rights initiative,” she said. “That’s how I see it.”

So a year and a half ago, she took a small but unusual step in the hierarchical world of county bureaucracy: She sent a letter to a county supervisor and asked for a library.

“Many of the small libraries in the living units are in dismal condition,” Gallegos wrote to Supervisor Don Knabe, whose district includes Los Padrinos. “We hope you can allocate funding that will replace old worn-out books. Lastly, please consider building a state of the art facility that will include a county library, new classrooms that will support 21st century technologies (i.e. laptops, smart boards, & tablets), art and music rooms, and a recording studio. A county library would be a valuable resource that would greatly benefit our students.”

She brought the idea to James Johnson, the Los Angeles County Probation Department’s superintendent at Los Padrinos, as well, and he quickly agreed. Johnson knew there was a library at Central Juvenile Hall already, although that one is aging and smaller.

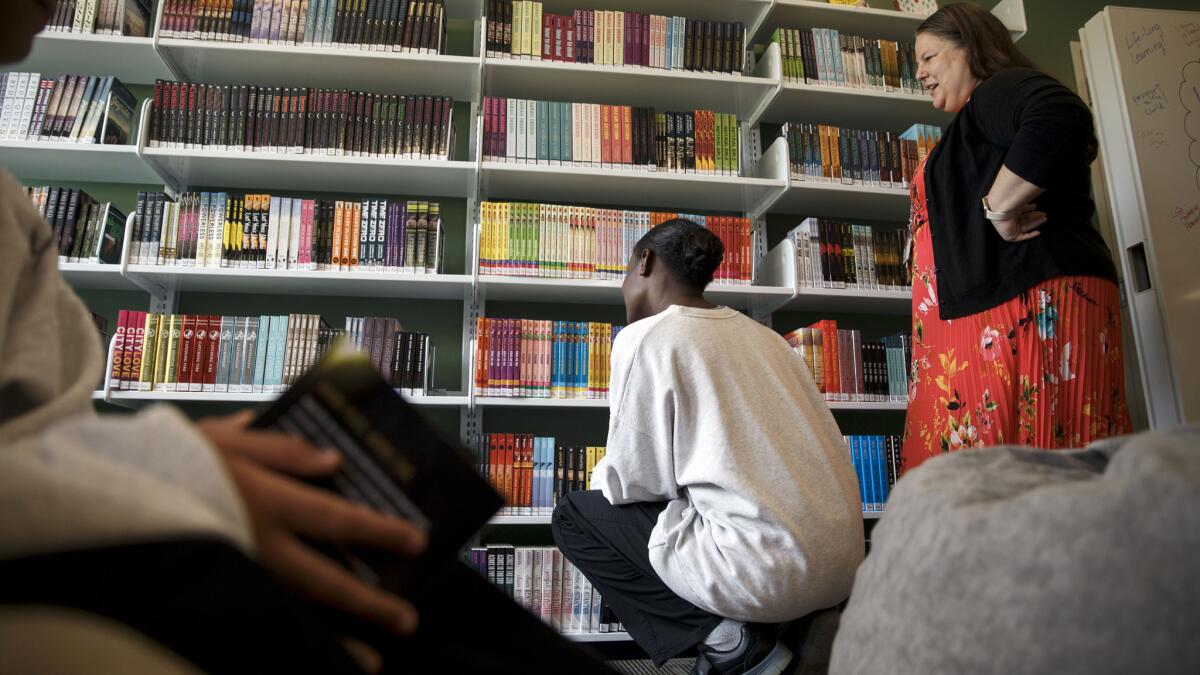

Last month, Gallegos watched as officials from the Office of Education and the county probation and library departments unveiled a new library at Los Padrinos with 4,000 books and a full-time on-site librarian. About $1 million in Probation Department funds were set aside to rehab an empty classroom, buy the book collection, and pay the librarian and assistant for the next three years.

A couple of weeks later, the first two minors walked through the door.

“I want to cry. I’m in book heaven,” said Christie, 16, as she looked around at the shelves.

She made the rounds with librarian Amy Trulock, pulling one book after another off the shelves before settling on “Hallway Diaries,” a collection of three stories by Felicia Pride, Debbie Rigaud and Karen Valentin.

The other girl, Vanessa, 16, curled up in a beanbag chair and began flipping through “On the Edge,” a tale of love and rival gangs by Allison van Diepen. Vanessa said she had read other books by the author and liked them because the characters “go through the same things we do.”

Vanessa said she reads more books when she’s in custody. “I don’t get as into them [at home] as I do here, because it’s all I have to do.”

Gallegos said she tries to make the most of having a literally captive audience to reel in kids who would otherwise shun reading. She likes to introduce her students to books through authors with experiences like their own — people like Luis Rodriguez, the 2014 poet laureate of Los Angeles, and Jimmy Baca Santiago, who wrote the screenplay for the 1993 cult film “Blood In Blood Out.” Both men have come to speak at the juvenile hall at Gallegos’ invitation.

Rodriguez said in an interview that a library “would have made all the difference in the world” when he was a teenager locked up in juvenile hall.

“I think there are opportunities, if you’re going to take young people away from their communities, from their families, to teach them something,” he said.

Some kids have taken an unlikely shine to more literary works. One detainee read 2 million words in six months, including most of the “Harry Potter” series.

“Here’s a kid with tattoos, gangster, and he’s reading ‘Harry Potter,’ ” Gallegos said. After showing the judge his certificates for all the books he had read, the youth’s sentence got knocked down from a year to six months.

Nick Ippolito, Knabe’s deputy on child welfare issues, said there should be libraries at all of the county probation camps and halls. But, he said, county leaders should focus on keeping kids from winding up in the lockups in the first place. Already, the numbers have decreased. The population of the three juvenile halls is down from a high of more than 1,700 in 2006 to less than half of that.

“Hopefully in the future as population numbers go down, we see less and less need for these facilities,” Ippolito said. “My hope is that we get to a point where we’re not just saying, ‘We have a library for you while you’re in jail.’ ”

Twitter: @sewella

ALSO

San Francisco police investigating possible hate crime after two tourists pepper-sprayed

Bullet train route across Big Tujunga Wash meets growing opposition

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.