Inglewood mayor defends destruction of police records as routine; activists continue to voice concerns

Inglewood Mayor James T. Butts Jr. on Sunday defended his city’s decision this month to allow the destruction of years of investigative records involving police shootings.

Many of those records would have become public for the first time under a new state law set to take effect Jan. 1, providing a window into a police department that for years was beset by allegations of excessive force, poor officer training and lack of transparency.

Butts, a former Santa Monica police chief, told The Times on Sunday that there is no connection between the new law and Inglewood’s action. The Times broke the story a day earlier on the council’s decision.

“This premise that there was an intent to beat the clock is ridiculous,” he said.

City officials, he added, would have nothing to fear from these records in terms of liability or embarrassment. A staff report indicates that the records go back as far as 1991.

“How would they be embarrassing to me?” said Butts, who became part of city government when he was elected mayor in 2011. “I wasn’t even here for those records. The records are what they are.”

The city’s decision attracted more than routine notice because of its timing and because it represented a change in city policy. Until this month, Inglewood required the Police Department to retain records on shootings involving officers for 25 years after the close of an investigation. Records of other internal investigations were to be kept six years.

Although these records were retained, they were not necessarily available to the public. That changes next week, because of Senate Bill 1421. The new law opens to the public internal investigations of shootings by officers and other major uses of force, along with confirmed cases of sexual assault by officers and lying while on duty.

Still, Butts maintained the city did nothing wrong.

“It’s actually quite routine for us to do records destruction,” he told ABC 7’s Eyewitness News. “The Finance Department, the Police Department and other entities — whenever they want to destroy records that exceed a time limit — they submit a staff report to the City Council and the City Council approves or disapproves the records destruction.”

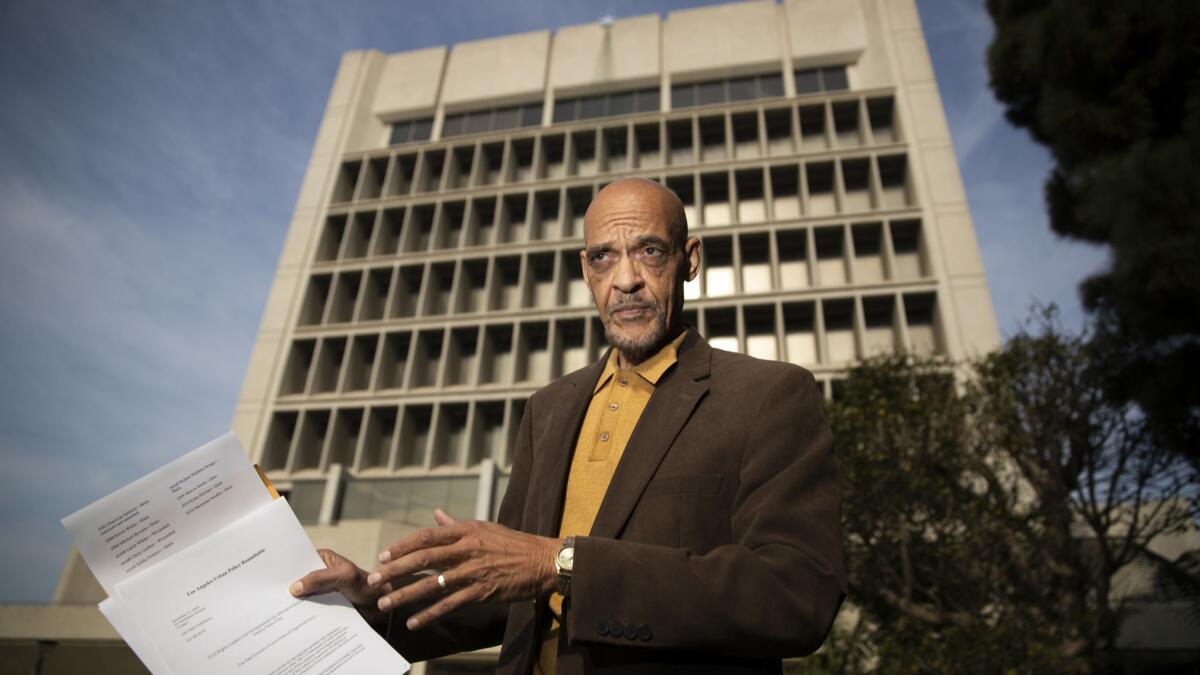

But longtime community activist Earl Ofari Hutchinson and a group of local civil rights leaders are skeptical. In light of the new state law, he said, Inglewood’s action “continues a pattern of lack of accountability.”

For years, Hutchinson worked with the families of those killed in encounters with Inglewood police. He said a full disclosure under the new law could reveal new avenues of legal redress and also could provide families with important details about what happened to their loved ones. The documents also would allow the public to review how well the department handled internal investigations and how seriously the department has embraced reforms.

“This action sends a terrible message that lack of transparency is still the policy in Inglewood,” he said. Hutchinson called on city leaders to delay the destruction of documents.

The city staff report and the City Council’s resolution from its Dec. 11 meeting make no mention of the new police transparency law. The resolution says that the affected records are “obsolete, occupy valuable space, and are of no further use to the Police Department.”

Butts told The Times Sunday said that the city’s old retention policy dated from 2010 and, before then, there was no policy regarding records of closed cases.

A series of Inglewood police shootings around 2008 attracted heightened scrutiny from activists, media and federal investigators. The city’s policy on retaining records was adopted as city officials and the Police Department were trying to improve their practices and rebuild public confidence.

However, the 2010 policy eventually became an administrative burden, Butts said, because it applied to any discharge of a weapon, including cases when a dog charged an officer or when officers fired a weapon and no one was hit. The more serious cases no longer had any active threads, he said, because the related civil lawsuits had been settled and criminal investigations concluded.

But Marcus Benigno, a spokesman for the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California, called Inglewood’s actions an attempt to thwart “the will of Californians.”

In the past, California police have shredded records to avoid scrutiny. In the 1970s, the Los Angeles Police Department famously destroyed more than 4 tons of personnel records after defense attorneys began requesting them. The move resulted in the dismissal of more than a hundred criminal complaints.

In response, the Legislature demanded that records be preserved but then took other measures, supported by police unions, to ensure the public had little access to them. The new legislation begins to unwind those restrictions.

Butts called the current incarnation of his city’s police department a model agency, despite a 2016 incident in which Inglewood police opened fire on a couple found sleeping in a car, killing both. Butts noted that five officers involved in that shooting no longer work for the department and that a review of the officers’ actions, which could lead to prosecution, is ongoing.

State law requires holding onto police records for at least five years and Butts said it makes sense for Inglewood to align with that standard.

Butts said he does not know whether documents already have been destroyed. The Police Department could have acted anytime after the City Council’s decision earlier this month, he said.

He is not inclined to reconsider.

“Then how long do you keep these records?” he said. “Do you keep these records forever? You’re not going to do that.”

Twitter: @howardblume

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.