10 years after Hurricane Katrina, tales from those who came to call L.A. home

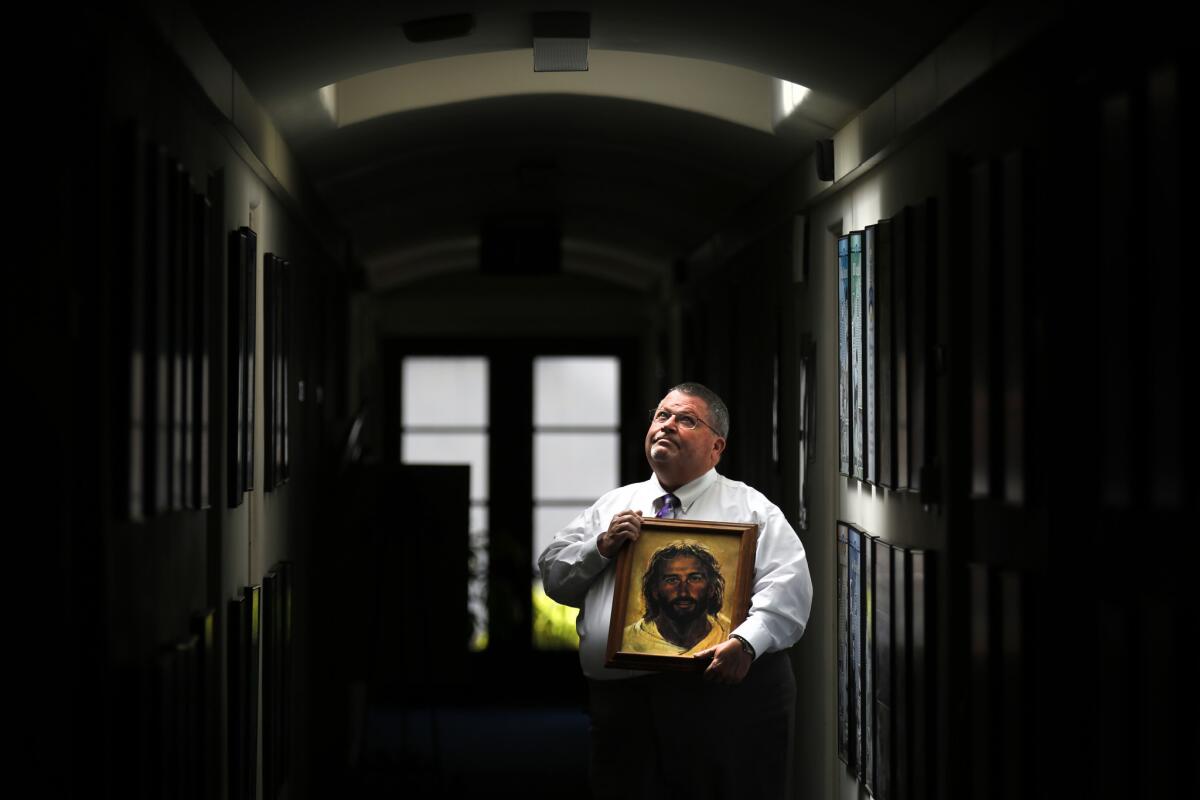

Terry McGaha, director of mission outreach and parent/volunteer programs at Notre Dame High School in Sherman Oaks, left New Orleans in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. He had worked at Holy Cross School in New Orleans for 31 years, and when the hurricane hit, he spent a week on campus with others before being rescued by boat.

Terry McGaha sat on a balcony in New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward sipping Crown Royal and staring into the early evening sky as helicopter lights strafed the encroaching Mississippi River.

His home in nearby St. Bernard Parish had taken 4 feet of water as Hurricane Katrina made landfall, and like the vast majority of the area’s 68,000 people, he was homeless. Now, he was hunkered down, eating ham and cheese po’ boys and listening to a tiny transistor radio with three other people on the grounds of Holy Cross School, where he had been a student before becoming a teacher and principal for 31 years.

A week later, they escaped on rescue boats. McGaha was flown to Washington, then to Houston before finding himself, four days after Christmas in 2005, at the gates of Notre Dame High School in Sherman Oaks. One of the many dislocated residents to arrive by way of Katrina, McGaha became part of a small fraternity that ended up in Los Angeles, survivors transformed by the storm and their new home.

There are no precise numbers for how many people driven out by Katrina still live in California. A year after the hurricane, just over 1% of the people displaced were living in the Golden State, according to research conducted by University of Michigan professor Narayan Sastry and University of Wisconsin-Madison professor Jesse Gregory. Though small, that figure represents the largest landing point of any state not in the South. The study found that, at the time, 53% of adult men and women in New Orleans either stayed in the city or returned after the storm.

McGaha ships in coffee, andouille sausages and “Hurricane Mix,” to make the famed New Orleans cocktail. But he never called the city his home again.

Now an administrator at Notre Dame High School, McGaha took stock of the wreck of his 1912 home with white and green trim. He renovated it twice, but he went into debt and decided to rent it out. Eventually, almost imperceptibly, L.A. became home, his house across the street from the school his “Notre Dame Chateau.”

“Probably had I not moved here and found that there is great life outside of ‘N’awlins,’ as they would say there, I would be one of those who went back,” he said.

Being 30 minutes from the beach, the mountains and the desert — that was nice too.

::

Sandra Humphrey doesn’t like Santa Monica.

She lives with her daughter and 2-year-old grandson in a tiny ground-floor apartment. She pines for her friends on Hayne Boulevard in New Orleans East. Her daughter, Benell Grant, 45, is happy that her mother replaced the fried food and smoking she fancied with a more healthful lifestyle that includes juice shakes. Humphrey does not love the beach like her daughter does, and she misses the folks back on Hayne Boulevard, who she said “had spunk.”

The 65-year-old had gotten used to the rhythms of a New Orleans neighborhood that had been at the epicenter of white flight in the 1980s and 1990s. She lived on the edge of Lake Pontchartrain, and her dad ran a juke joint.

Sometimes, at night, nightmares wash over Humphrey in waves, especially around each anniversary of the storm. She lived through the ghastly experience of the Superdome, before catching a bus to Houston, and then a flight from Atlanta to L.A.

“It’s like I’m going through that nasty, stinky water, and it’s getting all in my mouth,” she said. “I still get very upset and angry.”

She remembers the Saturday that her daughter called from L.A. to ask if she was going to evacuate as the storm approached.

“I told her I was cooking stuffed pork chops and succotash and wasn’t going nowhere,” Humphrey said.

She misses New Orleans, but with each trip she takes back with her daughter, Humphrey’s desire to return for good has faded.

It’s not the same.

::

Los Angeles saved Jamar Franklin’s little girl. Or, more precisely, a child of L.A. saved her.

The Saturday before the storm, Franklin, 41, had been playing tennis with a friend when his wife, Tirzah, called and told him to get home. He had been a history and math teacher and basketball coach at Holy Cross School at the time.

“I had told my players I would see them on Monday,” he recalled. “When I was in high school, we used to have hurricane parties. We weren’t worried.”

But soon the Franklins and their toddler, Marley, were fleeing for Dallas.

Stuck in a hotel for weeks, they had to constantly get ice to keep their daughter’s medicine for sickle cell anemia from spoiling. It was a constant worry.

The Franklin family finally made it to L.A. when Tirzah, about a month after leaving New Orleans, found a temporary position at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center’s labor and delivery unit.

“When we found our apartment” in L.A., Jamar said, “we walked in to open the door, and we were like, ‘Yes, we have a refrigerator and a stove. Yes!’”

Jamar stayed home to care for Marley as Tirzah’s job became permanent. He missed New Orleans and crawfish bisque, but caring for his child became his obsession as her condition worsened.

Back in their Gentilly neighborhood in New Orleans, Jamar’s parents lived next door. They could always lean on them. But not in L.A.

“We’re out here by ourselves,” said Franklin. “That was the biggest thing. Missing friends and family. I just felt like I should’ve gone back, but I couldn’t go back.”

Three years into living in L.A., the Franklins still weren’t sure whether they would ever go back to New Orleans.

In 2010, the couple had another daughter, Maya. By then, Marley’s risk of stroke had increased dramatically. She required blood transfusions every few weeks.

“We needed to make her better,” Franklin said. “Something was going to be done.”

Then doctors discovered that Maya and Marley had almost exactly the same blood type. Marley could get a bone marrow transplant thanks to her baby sister.

For Marley, this meant months of painful chemotherapy and 100 days of being confined to their home.

But her life was saved. The Franklins knew they would not be leaving L.A.

Jamar found work in the film and TV industry, eventually meeting Eric Monte, the man who created “The Jeffersons” and “Good Times.” Monte was homeless and broke at the time, but Jamar became his manager. A “Good Times” movie, with Monte as one of the executive producers, is in the works.

Marley Franklin, 11, now excels at golf, regularly beating girls several years older than her.

“This is a better life for my family right now,” Jamar said.

He still daydreams about having a home along a Mardi Gras parade route, but this is his home now. Like McGaha and Humphrey, Jamar and Tirzah Franklin kept one digital relic from New Orleans: their 504 area code.

When Marley got her first cellphone, she asked for those three digits that were so meaningful to Mom and Dad.

Twitter: @boreskes

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.