Arts education in all schools needs to be a priority and better funded, advocates say

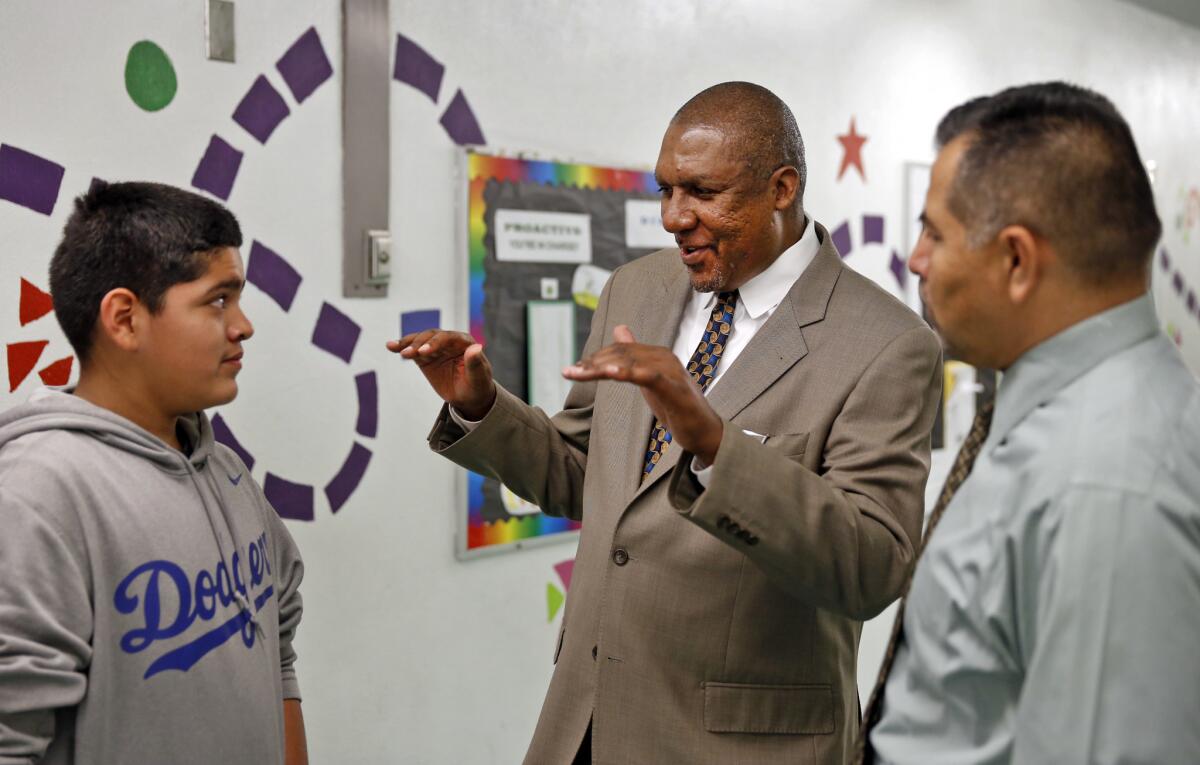

L.A. Unified School District Arts Education Executive Director Rory Pullens, center, visits Normandie Elementary School.

Getting school districts on track to offer state-mandated arts programs could require incentives, legislation and enforcement, arts advocates said at a hearing Friday in Beverly Hills.

Arts programs across California have waned in the wake of budget cuts and a sharpened focus on academic subjects measured on standardized tests. Thousands of students in the state don’t have access to arts classes, a violation of state law.

“How do we really force compliance?” said state Sen. Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica), chairman of the Legislature’s Joint Committee on the Arts, at a hearing focused on improving arts education.

“How do we really make the case to our school boards and to our superintendents that this is an important part of code?” Allen said. “We’re going to help them put in place good programs, but it’s got to be a non-negotiable portion of the curriculum.”

State law requires that schools provide music, art, theater and dance at every grade level. But the law lacks teeth and few districts across the state live up to the requirement.

Lupita Cortez Alcala, deputy superintendent of the California Department of Education, said the state should focus on providing incentives to school districts such as offering professional learning opportunities, providing funding to share best practices and working to make sure teachers are certified in teaching the arts.

She said districts are not trying to skirt the law, they just need help. Many, she said, may not even know the law exists.

“They realize how important it is and they’re just feeling really overwhelmed,” Cortez Alcala said. “We’re just coming out of the recession.We’re still at 46 out of the 50 states in per-pupil spending. We’re not quite where we used to be.”

But Carl Schafer, a veteran arts educator who has been meeting with lawmakers and state leaders to make sure districts are complying with the law, said for far too long arts education has been treated as an option.

Schafer joined parents, teachers and educators who offered solutions that ranged from providing more training to requiring districts to publicly disclose their level of compliance with state law. He warned that districts that don’t comply could face litigation.

“All of these efforts, and my own, have been to persuade,” Schafer said. “Persuasion has not worked and persuasion will not work in the future. The only solution is to require compliance.”

Eight out of every 10 elementary schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District don’t have the programs needed to meet state requirements, according to a Los Angeles Times analysis.

This year, L.A. Unified asked all of its schools to complete surveys detailing class offerings, the number of arts teachers and the help provided by outside groups for arts programs. A Times analysis, which used L.A. Unified’s data to assign letter grades to arts programs, shows that only 35 out of more than 700 schools would get an “A.”

“When you look at the disparity between those schools that were ranked exemplary with As and those schools that were Cs and Ds, it was staggering to see that in a district of this size only 35 schools were ranked as an A in the arts, given all this criteria,” District arts director Rory Pullens said. “It just gives you a sense of the magnitude of the work that we are going to have to engage in to make that change.”

Pullens said that work includes directing additional funding and teachers to campuses with the fewest resources and building a relationship with the city’s entertainment industry.

Craig Watson, director of the California Arts Council, said leaders must work to get the public engaged and invested in arts education.

“What’s wrong with this picture that we sell ourselves globally, appropriately, as the most creative place in the world and yet we have this disconnect over what we’re doing with our children and the workforce of the 21st century,” Watson said.

Educators told lawmakers that while more than 170,000 students take theater and dance in California, the state does not offer a separate credential for either subject. The reason, they said, was a typo in legislation that required credentials for music and art, instead of music and arts.

“It sounds like a bill possibility,” Allen said to applause from the audience.

For more education news, follow @zahiratorres on Twitter.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.