California loosens Jessica’s Law rules on where sex offenders can live

California officials announced Thursday that the state would stop enforcing a key provision of a voter-approved law that prohibits all registered sex offenders from living near schools.

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation said it would no longer impose the blanket restrictions outlined in Jessica’s Law that forbids all sex offenders from living within 2,000 feet of a school or park, regardless of whether their crimes involved children.

High-risk sex offenders and those whose crimes involved children under 14 will still be prohibited from living within a half-mile of a school, the CDCR emphasized. Otherwise, officials will assess each parolee based on factors relating to their individual cases, the agency said.

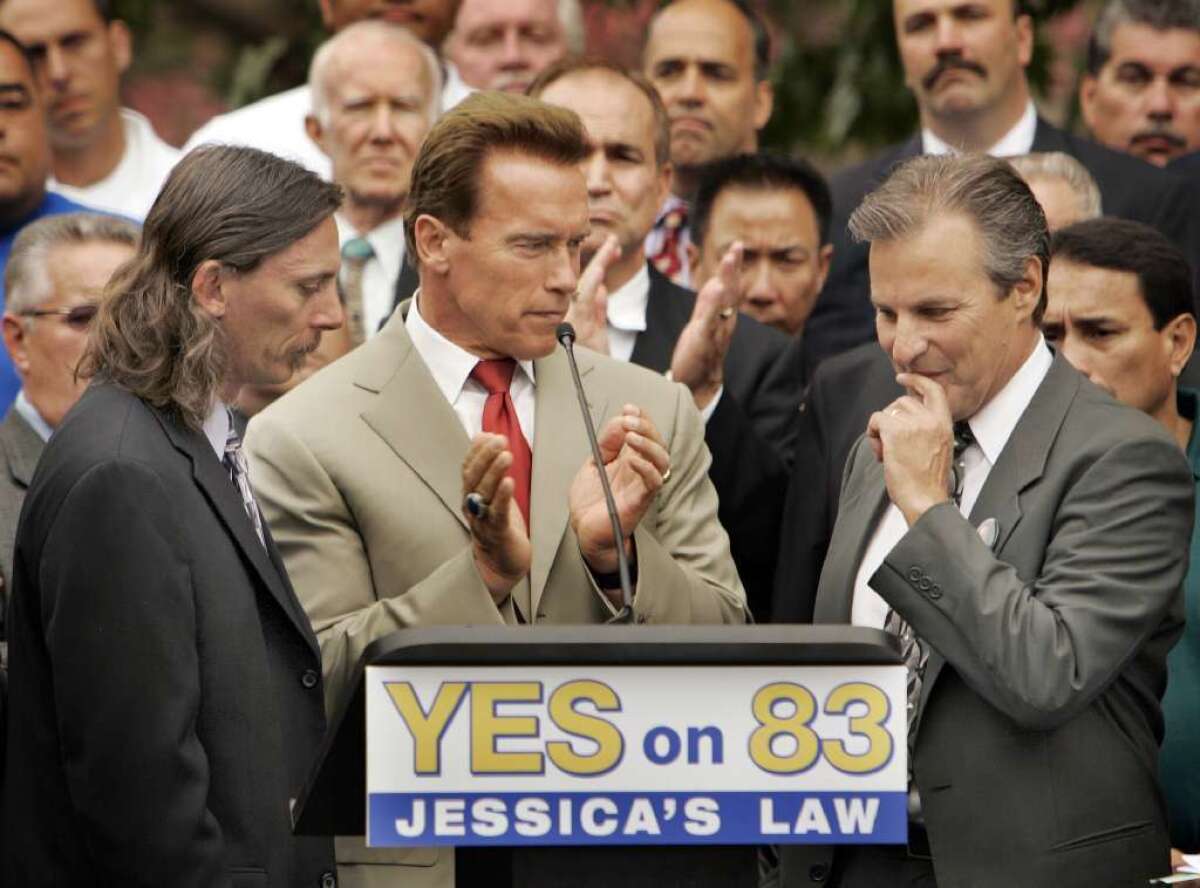

The shift comes nine years after California voters approved the controversial law, which has made it difficult for some sex offenders to find places to live.

The California Supreme Court on March 2 unanimously ruled that Jessica’s Law violated the constitutional rights of parolees living in San Diego County who had argued that the limitations made it impossible for them to obtain housing. As a result, advocates said, some parolees were living in places like riverbeds and alleys.

“While the court’s ruling is specific to San Diego County, its rationale is not,” CDCR spokesman Luis Patino said Thursday. “After reviewing the court’s analysis, the state attorney general’s office advised CDCR that applying the blanket mandatory residency restrictions of Jessica’s Law would be found to be unconstitutional in every county.”

The CDCR sent a memo to state parole officials on Wednesday outlining the policy change. The directive said residency restrictions could be established if there was a “nexus to their commitment offense, criminal history and/or future criminality.”

The memo said officials would soon provide further direction on how to modify conditions for parolees currently already living in the community.

In its ruling, the Supreme Court determined that the blanket policies for parolees “severely restricted their ability to find housing.” Justice Marvin R. Baxter, who is now retired, wrote that the rules “increased the incidence of homelessness among them, and hindered their access to medical treatment, drug and alcohol dependency services, psychological counseling and other rehabilitative social services available to all parolees.”

A CDCR report found that the number of homeless sex offenders statewide increased by about 24 times in the three years after Jessica’s Law took effect. Parole officers told the court that homeless parolees were more difficult to supervise and posed a greater risk to public safety than those with homes.

One of the San Diego County parolees who challenged the law was convicted of a sexual assault on an adult woman in 1991. That man, who had several serious illnesses, wanted to live with a relative who was a health professional, but he couldn’t because of the residency restrictions. Instead, he stayed in an alley behind the parole office.

The court ultimately determined that the residency restrictions did not advance the goal of protecting children and infringed on parolees’ constitutional rights to be free of unreasonable, arbitrary and oppressive government action.

Times staff writer Maura Dolan contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.