‘Stop-and-frisk in a car:’ Elite LAPD unit disproportionately stopped black drivers, data show

After an increase in violent crime in 2014, LAPD’s Metropolitan Division increased its use of traffic stops. Black drivers were stopped more often.

To combat a surge in violent crime, the Los Angeles Police Department doubled the size of its elite Metropolitan Division in 2015, creating special units to swarm crime hot spots.

Metro officers in unmarked, dark-gray SUVs began pulling over drivers to search cars for guns or drugs. By 2018, the number stopped by Metro was nearly 14 times greater than before the expansion.

The effectiveness of the strategy is hard to assess: Crime continued to rise for several years before dipping in 2018.

But it has caused a shift that some consider alarming: Metro officers stop African American drivers at a rate more than five times their share of the city’s population, according to a Times analysis.

Nearly half the drivers stopped by Metro are black, which has helped drive up the share of African Americans stopped by the LAPD overall from 21% to 28% since the Metro expansion, in a city that is 9% black, according to the analysis.

Metro makes most of its vehicle stops in South Los Angeles, which is almost one-third African American. But even there, the percentage of black drivers stopped by Metro is twice their share of the population, the analysis found.

The data analyzed by The Times do not show why an officer pulled over a driver. It does not contain information about whether a driver was searched, ticketed or arrested after the stop. Nor can the data prove that Metro officers are engaged in racial profiling.

But some civil rights advocates say the racial disparities revealed by The Times’ analysis are too extreme to be explained by other factors and troubling for a department that has spent the last quarter-century trying to repair its fractured relationship with the city’s black residents.

Connie Rice, a civil rights attorney who has worked closely with the LAPD on reforms in recent years, called the racial breakdown of Metro stops “really off the chain.”

“This is stop-and-frisk in a car,” she said, referring to the New York Police Department’s controversial practice of patting down black and Latino pedestrians, which was sharply curtailed after a legal settlement.

“Do you want the trust of the poorest communities, that are the root of the [1992] riots, or do you continue … massive stop-policing that creates mistrust?” she added.

Chief Michel Moore, an LAPD veteran who took over the department in June, said the Metro command staff “is very aware of the potential of people viewing them as over-policing or being overly harsh.”

But he argued that intense policing is necessary in high-crime areas to keep residents safe.

“A person who’s living in these … communities is experiencing a disproportionate level of violence than other Angelenos and is suffering from that,” he said. “And the symptom, that means there are more police officers there. It’s been my experience that that’s where the community wants us. The people who are experiencing the violence are asking for us to be there to help them.”

He noted that LAPD officers are trained to recognize their own implicit racial bias and that the department conducts random reviews to ensure that stops are constitutional.

“We can and should look at the conduct of officers that conduct frequent proactive activity to ensure that there’s a fairness when they’re exercising discretion, that it’s not just hunch policing, that they’re not just stopping everything that moves, per se, because that’s not lawful or right,” Moore said.

This is stop-and-frisk in a car.

— Connie Rice, civil rights attorney

While some critics of the LAPD acknowledge that it has made important strides in improving community relations, a 2016 survey by the department showed that less than half of black residents consider the police to be honest and trustworthy — a rate far lower than that of other Angelenos.

This credibility gap is ingrained in history.

Memories are still strong of the Dalton Avenue raid in 1988, where phalanxes of police officers armed with sledgehammers and crowbars demolished a South L.A. apartment building, as well as the brutal beating of Rodney King and the riots that followed in 1992 after the officers were found not guilty.

Recent fatal shootings of unarmed black men have contributed to the continuing distrust.

Precious McLaughlin is too young to remember the riots, but her feelings about the police are complicated. She often sees unmarked police SUVs, which are typically driven by Metro, cruising near her house on Arlington Avenue near West 48th Street.

“Somebody is less likely to do something they’re not supposed to,” said McLaughlin, 24, a warehouse worker.

The downside, she said, is that the frequent patrols “open up the door for harassment, being overbearing in the community, creating distrust between the community and the police.”

Crips claim the north side of West 48th Street. To the south are the Van Ness Gangsters, a Bloods gang.

In the surrounding blocks, Metro officers have pulled over thousands of drivers in recent years, and the proportion of African Americans is among the most skewed in the city.

In an area east of McLaughlin’s house, stretching from South Van Ness Avenue to Denker Avenue, 41% of residents are black, while 81% of the more than 2,000 drivers stopped by Metro officers since 2015 were black, The Times’ analysis found.

Nearby in the Exposition Park neighborhood, a 39-year-old youth counselor said he had been pulled over by the LAPD three times in the previous month while driving home from Martin Luther King Jr. Park. Twice, the officers were in unmarked SUVs.

In one encounter, officers in a gray, unmarked SUV began following him near a liquor store at West 39th Street and South Western Avenue, said the youth counselor, who did not want his name used because he fears police harassment.

Initially, he stepped on the gas to avoid them. When he stopped, they said he was speeding and asked whether he had anything in his car, he said. He allowed them to search it, and they left without giving him a ticket.

The youth counselor is among the members of the Rollin’ 30s Harlem Crips who hang out at King Park but say they have regular jobs and no longer live the gang lifestyle. He suspects he was targeted because of his race as well as his affiliation with the gang.

His black Audi has paper plates — another reason why police might have singled him out.

“It seems like they got license to kill and harass black people,” he said. “I don’t got nothing, so I don’t get too upset, but there’s an aspect of getting harassed, [messed] with all the time.”

Metro is less active here than in McLaughlin’s neighborhood, making 900 vehicle stops since 2015. But the race of the drivers who were pulled over is similarly lopsided — 78% black, compared with a black population of 32%.

On another day, a 64-year-old retired water plant worker was playing pinochle at King Park with a friend.

In 2016, he said, officers in an unmarked SUV stopped him near West Jefferson Boulevard and South Western Avenue, accused him of almost crashing into them, then searched his car.

“They think all black people have been to prison, got a record,” said the man, who would not give his name and said he was not a gang member. “The first thing they ask is, ‘Are you on probation or parole?’ ”

The LAPD denied The Times’ request to interview Metro command staff and accompany Metro officers in the field.

During a ride-along two years ago, Metro officers told a Times reporter that they try to be polite to drivers and explain the reason for each stop. They know people are watching them and judging their actions, they said.

**

In April 2015, with violent crime up 26% and shooting victims up 24%, Mayor Eric Garcetti announced the Metro expansion in his State of the City address.

Unlike regular patrol officers, Metro officers often spend their entire shifts on vehicle stops and other “proactive” policing tactics intended to root out violent criminals.

They typically use a violation such as a broken tail light as a starting point to question the driver and potentially get inside the car — a type of stop known as a pretextual stop, which Moore acknowledged is more invasive than an ordinary traffic stop.

As the highly selective division — which is trained in paramilitary tactics and is the only LAPD division required to pass regular physical fitness tests — recruited new members, crime continued to spike.

That August was the deadliest in eight years, fueled largely by gang killings in South L.A. The trend continued into 2016, with homicides surging more than 27% in the first two months of the year.

The following year, homicides and shootings went down in South L.A., decreasing again in 2018.

Violent crime overall — which includes homicide, rape, robbery and aggravated assault — rose 22% in South L.A. in the first two years after the Metro expansion, with a modest decrease in 2018.

By 2018, about 270 of Metro’s approximately 400 officers were assigned to crime-suppression platoons. This month, about 70 Metro officers were reassigned as part of a push to increase the LAPD’s regular patrol ranks. But the division is still roughly double its original size, with a crime-suppression platoon in each of the LAPD’s four geographic bureaus, Moore said.

Metro officers are a tiny fraction of the LAPD’s 10,000 sworn personnel, but they have an impact beyond their numbers.

As measures of success, then-Chief Charlie Beck cited felony arrests by Metro officers, which more than tripled in the initial months of the expansion, as well as arrests of gang members by the division, which increased nearly fivefold. The Times requested recent statistics for the number of guns seized by Metro, which officials have cited as a key metric, but a department spokesman was unable to provide them.

The number of vehicle stops by Metro officers has skyrocketed from about 4,300 in 2014 to nearly 60,000, making up about 11% of all LAPD stops last year, The Times’ analysis showed.

Even though Metro deploys a crime-suppression platoon in each geographic bureau, its vehicle stops are concentrated in South L.A. and a few other areas with relatively high crime, including Westlake and Panorama City, with wealthier, whiter parts of the city recording few Metro stops.

Where violent crime is low, Metro concentrates on property crimes such as burglaries and auto thefts, which may involve techniques other than stopping drivers.

In much of Brentwood, Pacific Palisades, Silver Lake and Los Feliz, Metro officers have not stopped any drivers at all since the expansion.

More than 90% of the drivers stopped by Metro citywide since the expansion have been black or Latino. Metro stops black drivers 13 times more often than white drivers.

Latinos are slightly underrepresented in Metro stops, making up 49% of the population and 44% of stops. Whites, comprising 28% of the city’s population, account for less than 4% of the drivers stopped by Metro, according to the analysis.

Blacks are 9% of the city’s population and 49% of the drivers stopped by Metro.

In South L.A., The Times’ analysis found that traffic officers, whose primary mission is traffic enforcement, stopped a far lower proportion of black drivers than Metro officers did.

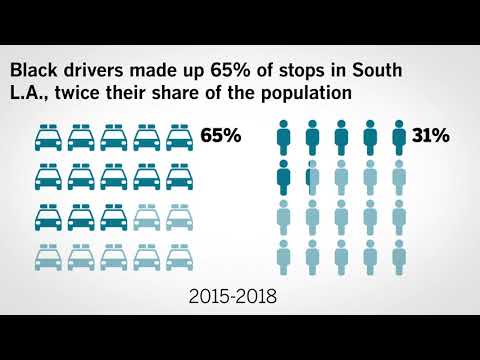

Since 2015, 45% of the drivers stopped by traffic officers were black, compared with 65% stopped by Metro, in an area where blacks are 31% of the population.

Metro officers are deployed based on crime trends and sometimes come from other parts of the city to stem violence in South L.A., as in the summer of 2016, when rising homicides led LAPD brass to consider emergency solutions.

“The problem here is that when you bring in outside units, they don’t know who is who,” said Jay Wachtel, a retired Cal State Fullerton criminal justice professor and former Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives agent. “They are going to wind up stopping a lot of people who don’t need to be stopped.”

The percentage of black drivers pulled over by Metro is “astounding,” said Peter Bibring, director of police practices for the ACLU of California.

“How do they decide who is involved in more serious criminal activity?” Bibring said. “That kind of extreme disproportionality on the basis of race suggests that race is playing a factor, whether consciously or not.”

**

In the aftermath of the Rampart corruption scandal, federal authorities in 2000 imposed a consent decree on the LAPD to correct pervasive civil rights violations, including excessive force and unreasonable searches and seizures.

Among the requirements was that the LAPD document its vehicle and pedestrian stops in detail.

After the decree was lifted, the department stopped producing a racial breakdown of stops, which is a standard metric for many police departments, or documenting what happens to drivers after they are stopped.

Whether a car is searched, a driver is patted down, contraband is found or an arrest is made can illuminate racial disparities and shed light on the effectiveness of the stops.

LAPD officers continued to collect information on the race of the driver, the time and location of each stop and the division of the officer who initiated it. A database available on a city website, which was used by The Times in its analysis, contains more than 5 million vehicle stops from 2010 to 2018.

In July, the LAPD resumed collecting post-stop data, as required by a new state law.

At a public hearing on racially biased policing in 2016, LAPD officials cited complaints filed by residents but did not include any racial data on vehicle or pedestrian stops.

The department typically receives a few hundred biased-policing complaints each year, mostly from African Americans. The complaints are almost never upheld.

Moore said he did not know why the LAPD quit analyzing the stops by race or collecting post-stop data. He questioned the data’s utility, citing variables such as the age of drivers or people who are passing through and do not live in the area.

“I don’t think that that number, whether it’s 28%, 9% or 90%, that it informs me about the rightfulness or wrongfulness of the officer involved,” Moore said of the percentage of African American drivers.

Metro’s focus on South L.A. is a reflection of the high levels of violent crime in that area, he said.

Last year, violent crime citywide decreased for the first time in five years, which Moore credited in part to crime-fighting strategies including the Metro expansion.

Steve Soboroff, president of the civilian commission that oversees the LAPD, said he “believes in the mission of Metro and the expansion of Metro.”

The disproportionate number of black drivers stopped by Metro is cause for concern, he said. But he said he needed more information, such as why drivers were stopped and how many traffic tickets Metro writes, to draw conclusions and figure out solutions.

Rice, the civil rights attorney, said the LAPD needs to conduct rigorous studies to prove that the Metro crime-suppression strategy is effective.

Rather than expanding Metro, the LAPD should have put more resources into community policing programs like the one that launched in Watts housing developments and is credited with reducing homicides there, she said.

“It indicates a fundamental structural problem with how they are deploying this strategy,” Rice said of the racial disparities in Metro vehicle stops. “They are only deploying it in areas where poor people and people of color are.”

Follow @bposton on Twitter.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![Irvine, CA - July 16: Gina Osborn, shown at her home, is the former head of Metro security is suing the agency for firing her after she filed a claim with the Inspector General. Photo taken at her home Tuesday, July 16, 2024. Gina Osborn, a former FBI agent who was the agency's first chief safety officer, "was summarily terminated by [Chief Executive] Stephanie Wiggins," said her attorney, Marc R. Greenberg. Osborn says in claims that she butted heads with Metro's CEO over security as the agency was trying to put a good face on its efforts to clean up crime and loitering. (Allen J. Schaben / Los Angeles Times)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/c1419ae/2147483647/strip/true/crop/5981x4000+9+0/resize/320x214!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F46%2F07%2Fa88ac0b7466895ee4e137839d93c%2F1467168-me-former-metro-security-chief-18-ajs.jpg)