How would the LAPD handle a riot today? More officers. More arrests. Better strategy

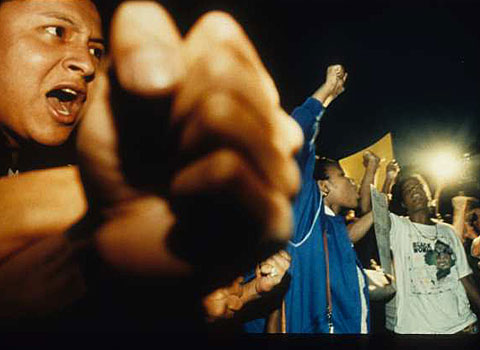

The riots that consumed Los Angeles 25 years ago had many causes — grinding poverty and hopelessness in South Los Angeles, a police force with a reputation for treating minorities poorly, the not guilty verdict against the white officers caught on tape beating black motorist

But the police tactics — or lack of them — in the crucial hours when the rioting began are also considered a major factor in why the city burned for three days.

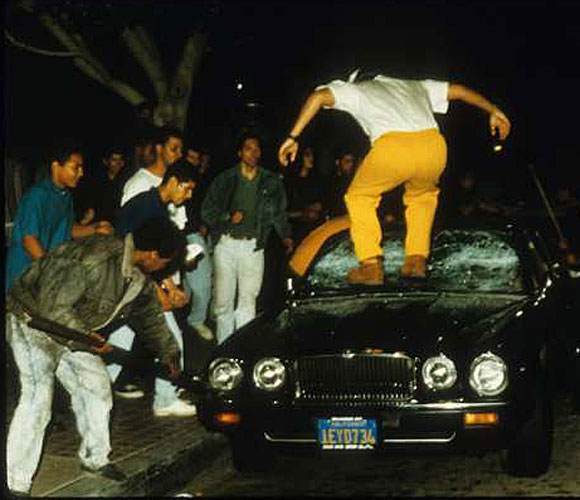

Despite deep concerns in the community about violence if the verdict was not guilty, the LAPD didn’t have a plan to deal with unrest. When the first flashpoint of violence erupted at the corner of Florence and Normandie, the LAPD moved in. But, outnumbered, the police infamously retreated.

For the next few hours, a horrified city — and world — watched on live television as rioters pulled motorists out of cars and beat them, set buildings on fire and looted stores, with no police in sight.

Those images haunted the LAPD for years after and represented to many an unacceptable breaking of civil order and government service.

“My belief is it’s a failure of the institution,” LAPD Chief Charlie Beck said in an interview this week.

Since then, police and others have analyzed what went wrong and how officials would deal with unrest now. Here’s a breakdown of these conclusions, through the eyes of LAPD Assistant Chief Michel Moore:

3:15 p.m.

A jury acquits Officers Stacey C. Koon, Lawrence M. Powell, Theodore J. Briseno and Timothy E. Wind in the King beating.

2017 tactics

Over the last 25 years, LAPD relations with community groups have improved dramatically, though they are still far from perfect. The LAPD regularly meets with various stakeholders and also has developed intelligence-gathering processes with former gang members.

5:25 p.m.

LAPD officers respond to the first report of trouble at the intersection of Florence and Normandie. Beer cans are being thrown at passing motorists.

2017 tactics

Moore said today, instead of pulling back, the LAPD would flood the zone with more officers. The idea would be to use overwhelming strength to put down the riots in the early stages, preventing them from spreading.

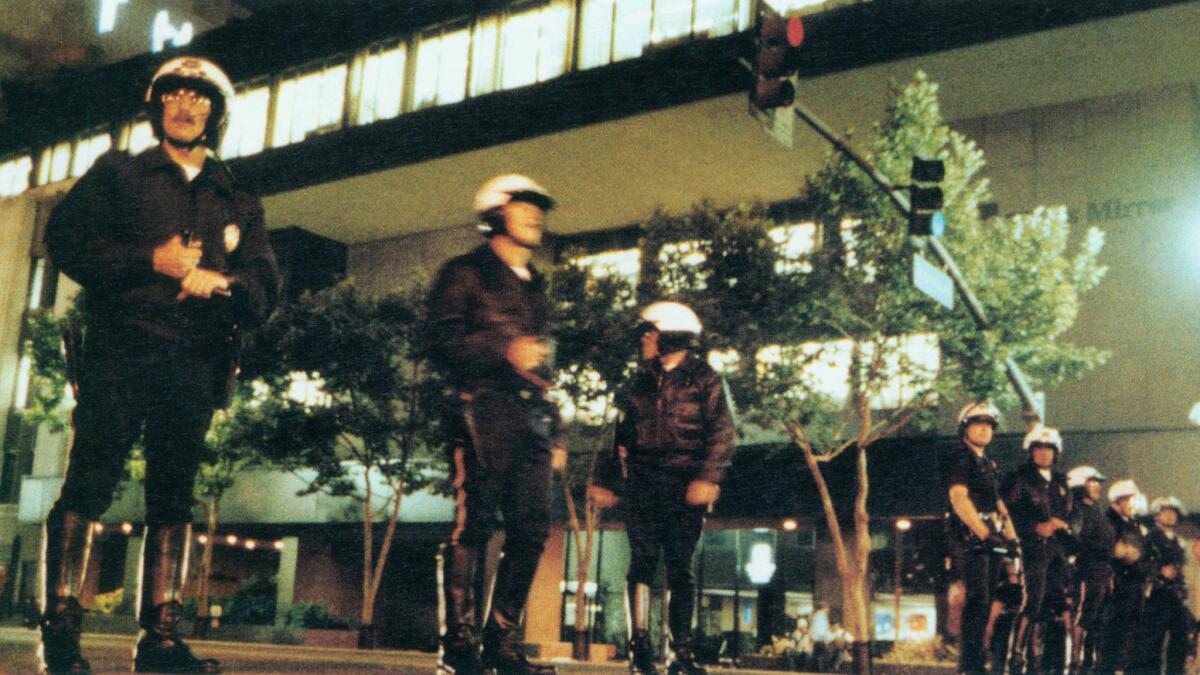

The department now has strategies developed after the riots to move platoons of officers to an area fairly quickly. They also use tactics to isolate troublemakers and if necessary deploy an array of less-lethal munitions to break up mobs.

The department would likely run the operation from a large command bus at the location. Commanders would try to limit the size of the crowd.

Moore said the LAPD in 1992 was concerned about being involved in major confrontations, given its image after the King beating. Top brass feared this could spark a riot. Ironically, it kept them from making the mass arrests that might have prevented the riots from spreading.

6:45 p.m.

TV footage shows Reginald Denny being dragged from his cab and beaten nearly to death at Florence and Normandie. Denny is rescued by four brave strangers.

2017 tactics

Today, the LAPD’s response is focused on not allowing pockets of unrest to spread. “You can never allow an exception for any level of violence or property damage,” Moore said. The assistant chief said the department has learned that even to allow a few broken windows can set off a chain of potentially deadly events.

Moore said the department in recent years has drawn the line at protesters entering freeways, and it has made more arrests than other departments across the country at demonstrations. He said that is in part preventive and reaction to a history many other cities don't have to consider.

After a shooting of a young, armed black man in South Los Angeles last October, protesters gathered, and at one point a car did doughnuts at an intersection and some people tagged buildings nearby. LAPD officers in helmets swarmed the area at 107th Street and Western Avenue and ordered the remaining crowd to leave or face arrest. Officers made a handful of arrests and eventually persuaded the crowd to leave.

8:30 p.m.

Chief Daryl F. Gates returns to the city's Emergency Response Center from a Brentwood fundraiser. He and Mayor Tom Bradley had not spoken to each other in more than a year before the unrest.

2017 tactics

The chief’s job was radically changed in the wake of the riots. Voters ended civil service status for chiefs. Before that, chiefs had been appointed by the Police Commission and essentially were allowed to serve indefinitely barring formal findings of serious wrongdoing. A law also limited police chiefs to two five-year terms. It also empowered the mayor to select a chief with the City Council's consent and provided for civilian review of police misconduct.

Twitter: @lacrimes

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.