Plan to dump rat poison on Farallon Islands questioned by California Coastal Commission

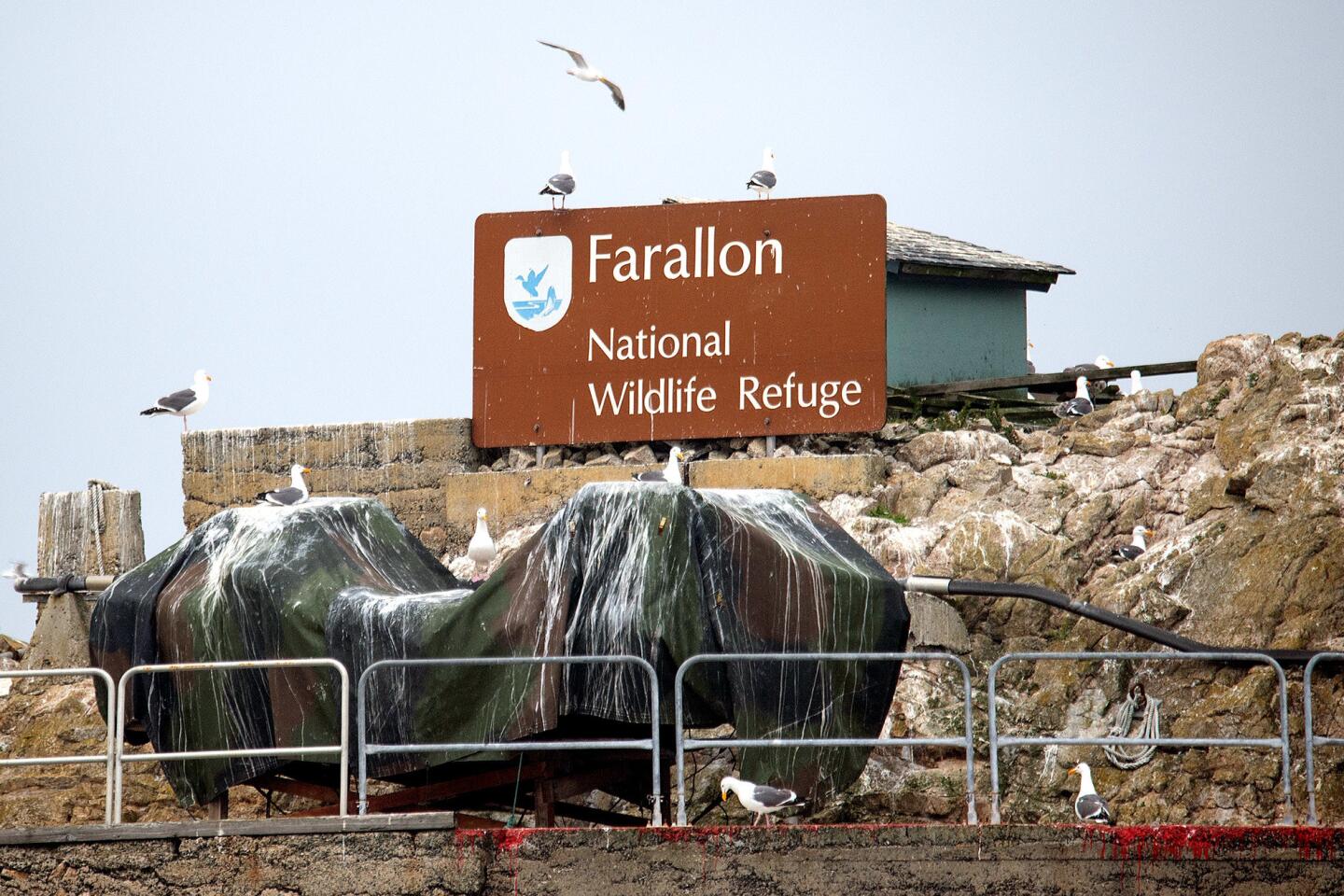

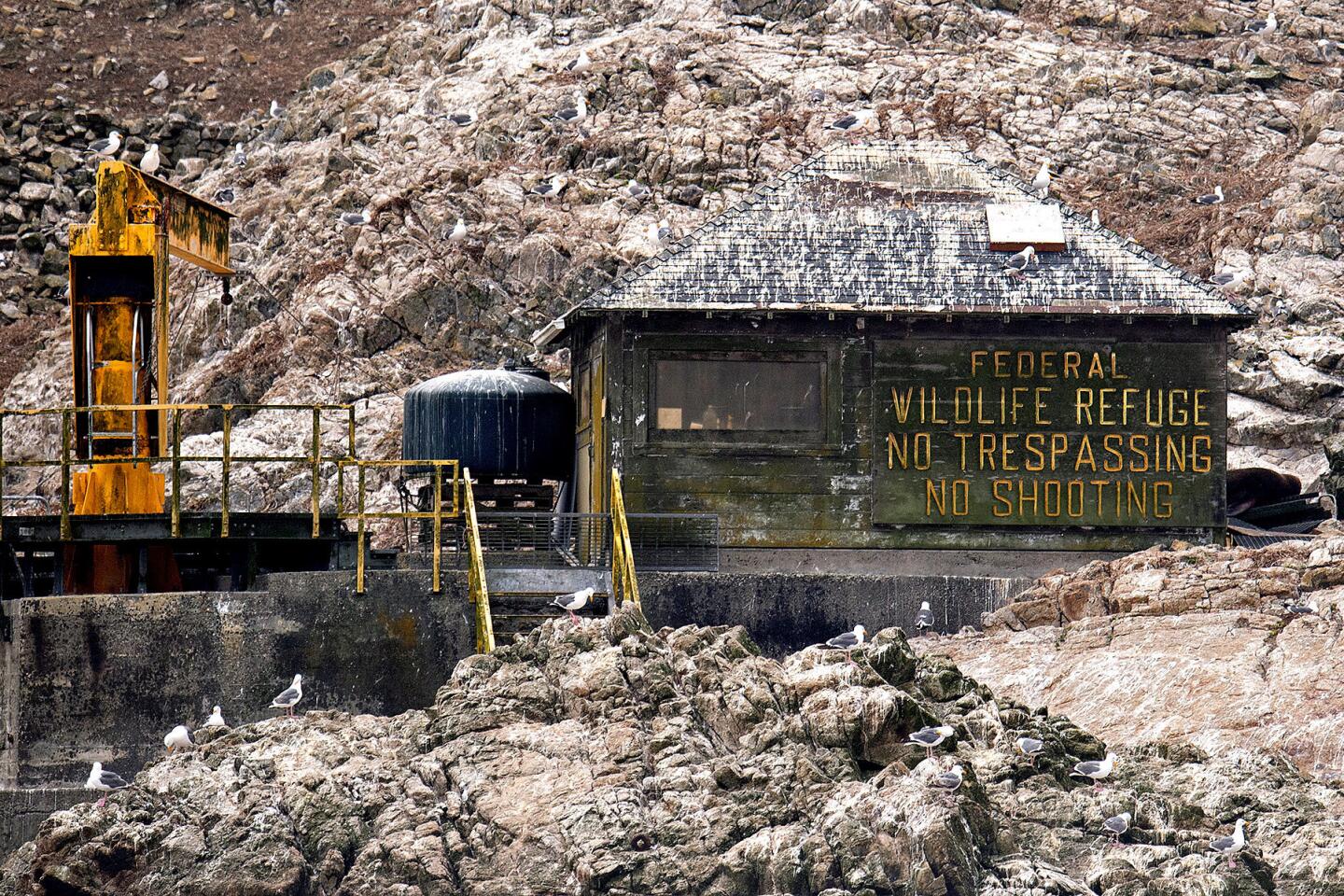

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service on Wednesday withdrew its request that the California Coastal Commission sanction its controversial plan to poison tens of thousands of invasive house mice on the rugged Farallon Islands.

Following nearly two hours of testimony and deliberation from the federal agency and conservationists, several commissioners seemed poised to vote against the project, which would involve scattering 1.5 tons of rat poison pellets over the islands, which lie just 27 miles off the coast of San Francisco.

“We haven’t been convinced this is the best and only way to go,” said Commission Chair Dayna Bochco.

Fish and wildlife biologists say they must kill the mice because they are wreaking havoc on a fragile ecosystem.

The federal government does not require the express permission of the Coastal Commission in order to go ahead with its plan. However, the body’s approval would help bolster public support and potentially stave off litigation.

After pointed questioning and criticism from some commissioners, however, the wildlife service announced that it was withdrawing its request for approval so that it could better formulate a response to the commission’s concerns.

“It’s in our interest to not have a conflict with the state,” said Doug Cordell, a spokesman for the Fish and Wildlife Service.

The islands boast one of the world’s largest breeding colonies for seabirds, including the rare ashy storm-petrel, whose population — half of which lives on the Farallones — has declined in recent decades.

The explosive growth in mice, which first landed on the islands during the California Gold Rush, has attracted burrowing owls, who not only eat the mice but also prey upon the storm-petrels. The mice also help spread invasive species and eat seed banks of native plants.

The federal government contends that the only way to get rid of the mice is to drop poison from a helicopter in two batches over three weeks. But Bay Area conservationists are worried that the poison, an increasingly controversial rodenticide called brodifacoum, will kill other species and make its way up the food chain.

The Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency that manages the Farallones, acknowledges that while some non-target species will likely be killed in the process, broadcasting poison over the islands is a tried-and-true method of tackling rodent infestations. Biologists say that the long-term benefits will far outweigh any collateral damage.

Coastal Commission staff last month released a report expressing support for the project, saying it was consistent with the state’s marine protection and water quality policies.

At Wednesday’s hearing, which was held in San Luis Obispo, the Fish and Wildlife Service said it looked at 49 eradication methods, including mouse fertility control and trapping, but ultimately decided that poison was the best approach because of its proven efficacy. The agency notes that 28 out of 32 mouse eradication projects undertaken worldwide since 2007 have been successful, and that native species in those places have flourished.

Commissioners were not convinced, however. They said they wanted more details on the other options before they approved the project. They also asked for a clear contingency plan for how the wildlife service would respond if the project failed. The agency has yet to develop such a plan.

Opponents of the proposal asked why rodent contraception wasn’t given more consideration. The wildlife service said that the technology has only been used on a limited basis, and hasn’t been tested in a mouse eradication setting.

“Why hasn’t it been tested? This could be a chance to test it,” Commissioner Carole Groom said. “This whole issue is very troubling to me,” she added later.

Commissioners also expressed concern over the possibility that birds would eat the poison — an anticoagulant that causes internal bleeding. If the poisoned birds fly to the mainland, they might spread the compound up the food chain, they said.

“It’s like dropping a nuclear bomb on this island, as far as I can see,” said Commissioner Roberto Uranga.

Conservationists point to failed eradication efforts in places like Rat Island in Alaska, where the same poison killed 46 bald eagles in 2008. The wildlife service said it has learned from its mistakes there.

The wildlife service says that while non-target species will be affected, robust mitigation efforts will keep collateral damage to a minimum. Until risk of poison exposure drops, the agency will scare away seagulls — the species most likely to eat the poisoned mice — using fireworks, predator calls and air cannons. Raptors such as owls and hawks that might eat the poisoned mice would be temporarily removed from the sanctuary until risk of poison exposure drops.

Criticism has mounted against brodifacoum in recent years after animals like mountain lions were found dead with rodenticide in their systems. California outlawed consumer use of the poison in 2014.

“We are very sensitive in California to this poison,” Bochco said. “We are afraid of this poison.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.