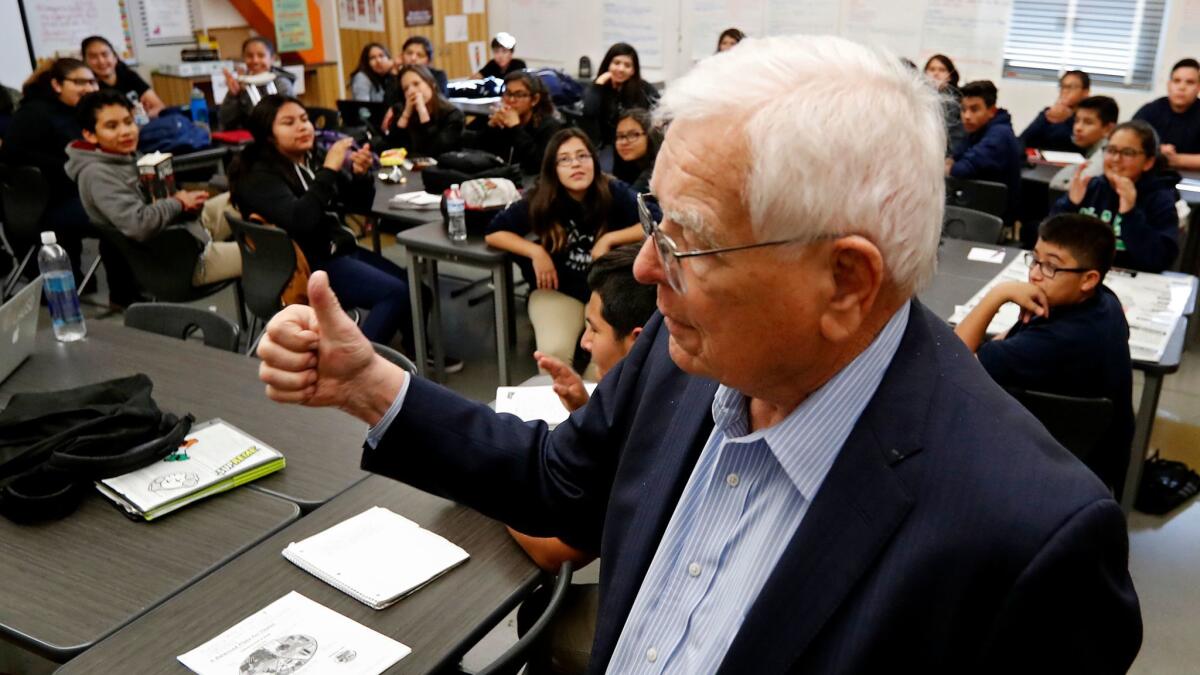

Built to last: Former LAUSD Supt. Roy Romer, 89, surveys $20-billion school construction effort

Former Los Angeles schools Supt. Roy Romer gave an A+ to the polished cement under his feet this month at the newly constructed Maywood Center for Enriched Studies.

The cement had the sheen of the tile flooring that is common in most schools, but it should last much longer and cost less to maintain.

“That is one of the things we learned as we built,” Romer said.

Romer pushed through the nation’s largest school construction project while superintendent from 2000 through 2006. The Colorado resident was back in the Los Angeles Unified School District to see the fruits of that labor, as part of an extended 89th birthday celebration this month.

The Maywood school, which opened in the fall, was the last of 131 new campuses in a $20-billion construction and modernization program.

There was plenty of skepticism about Romer when the Los Angeles Board of Education named him to lead the state’s largest school system. Other candidates had taken themselves out of consideration, and although Romer’s resume was impressive — as a former three-term Colorado governor and head of the Democratic National Committee — his background was in politics, the law and business, not education.

Romer quickly decided that a primary focus would be the classroom space crisis. Campuses were operating year-round, but individual students had schedules that resulted in nearly a month less of instruction. Many could not get the advanced courses needed to apply to selective colleges.

Before Romer’s arrival, the district had launched two high school projects but canceled both over environmental concerns, after spending some $250 million. A $2.4-billion bond issue in 1997 to repair schools was falling far short of the mark.

Romer got to work with the backing of a school board that, for the most part, got out of his way.

“He was a finisher,” said former board member Mike Lansing. “Ideas are aplenty, but finishers are not. He recruited and cajoled us on the board to overcome the politics and NIMBYism of a city that had been paralyzed by not meeting the need for decades. And he knew how to throttle up and down the pressure as needed.”

Romer worked with Mayor Richard Riordan and his successors to find parcels for schools in the crowded urban environment. But he also stood up to the city or developers in going after land projected for commercial projects. This included prime Wilshire Boulevard frontage at the site of the Ambassador Hotel, which Romer also visited during his return.

Romer also had to battle preservationists over that site. They wanted to save the historic hotel building.

The district agreed to recreate some historic elements. A Paul Williams-designed coffee shop was rebuilt as a faculty lounge. And the perimeter of the school library matched that of the hotel’s banquet hall, where Robert F. Kennedy in 1968 gave his final speech before being assassinated in the hotel pantry. Murals in the library commemorate Kennedy’s life.

Preservationists were not truly placated and the extras added major costs, which brought out critics of district spending. Still, the RFK Community Schools campus, which has six separate schools, got built.

“I remember how dense the student population of that area was — how you could fill up a school from the eight blocks around it,” Romer said.

Romer also insisted on completing the abandoned, half-finished Belmont Learning Complex, an infamous project whose rusting frames perched next to the 110 Freeway.

The site’s environmental problems were manageable, but the project had become politically toxic, contributing to election losses for school board members who supported it.

“He quickly figured out that Belmont was this symbol of failure and reviving it wasn’t just about seats for kids,” said former aide Glenn Gritzner. “He knew we just had to figure out how to get that school back. We had to prove to everybody we were not a failing district and we could get stuff done.”

The Belmont complex, renamed the Edward R. Roybal Learning Center, opened in 2008.

Romer and his team brought in needed expertise by importing “Seabees,” construction experts from the United States Naval Construction Battalions. He also worked to persuade voters to pass school construction bonds in 2002, 2004 and 2005.

After the first bond measure, Romer moved forward with a daring, potentially foolhardy strategy. Rather than use the money to pay for a relatively small number of projects from start to finish, he (and the school board) authorized work on all the needed schools. If subsequent local and state bonds had not passed, Romer could have been left with 80 holes in the ground and few schools — and a political catastrophe for all time.

“We had momentum to build these schools, and we needed to build them all,” Romer said.

The effort also survived another political gamble by putting the new schools — and thus the bond money — where they were most needed: in dense, high-poverty areas. That made sense for helping students, but it also meant that badly needed repairs were postponed indefinitely at schools that served more prosperous areas, which is where most voters live.

Within low-income communities, the district took flak for taking homes and small businesses from the very families the schools would serve.

By the time he left, Romer had won respect from many educators and district officials who’d had doubts. His original backers, however, in the corporate and philanthropic elite were less satisfied. They had hoped he would shake up the school system from top to bottom.

Although Romer also oversaw academic reform efforts, progress on that front has satisfied no one, including Romer.

“My only regret is that we couldn’t have done more and gone faster,” he said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.