There’s Koreatown. There’s Little Tokyo. So why can’t Leimert Park be Africa Town? Or Wakanda?

Bee Hall remembers when Leimert Park was the heart and soul of a vibrant black Los Angeles.

The blare of the horns and the beat of the drums filled the streets. Freshly brewed coffee wafted out of Fifth Street Dick’s cafe. Artists and art lovers perused galleries adorned with black art.

But over the years, as many black Angelenos moved out of South L.A. for cheaper housing and safer streets, Leimert Park lost some of its magic.

Her solution: Give the district a new name that celebrates its ethnic identity.

“This is Africa Town,” Hall said.

Or Little Africa. Or the Pan African Arts District. Or, in a nod to the hit Marvel movie “Black Panther,” Wakanda.

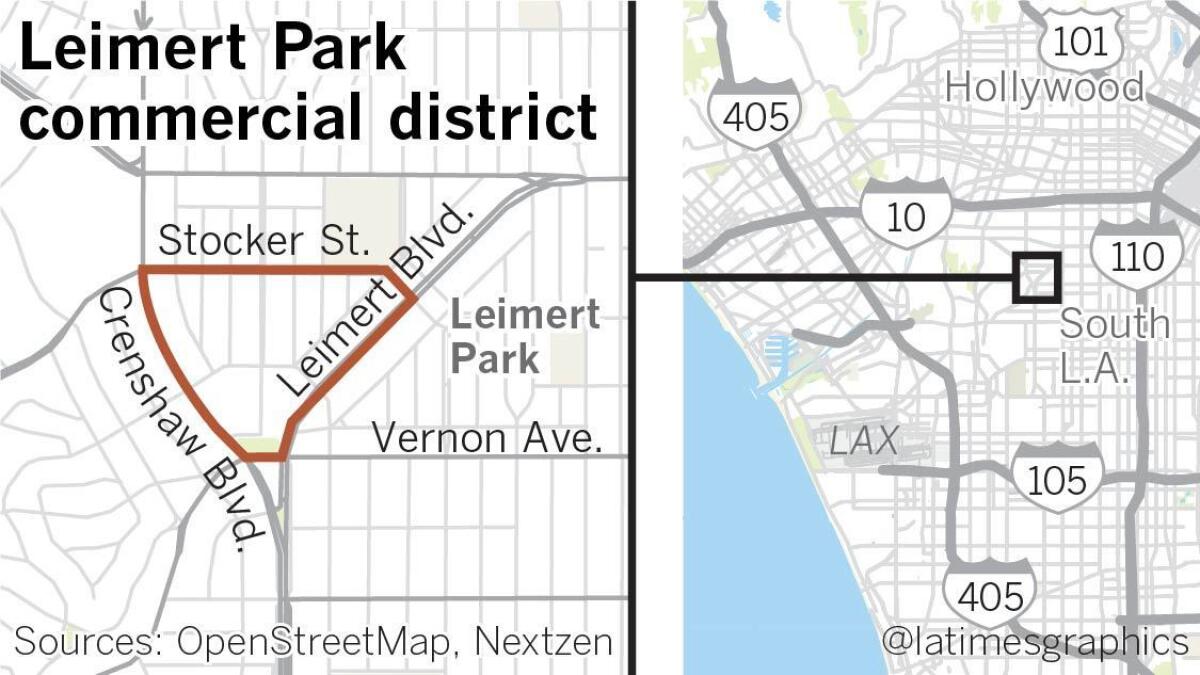

It all depends on who you talk to. Various groups have different visions, but each agrees that unlike with Koreatown or Little Tokyo, there’s nothing in Leimert Park’s name that tells residents or tourists that the triangular commercial district along Crenshaw Boulevard in South L.A. is the region’s epicenter of African American arts and culture.

In a city known for its diversity, the map of Los Angeles has been remade in recent decades as numerous neighborhoods have been rebranding to mark the immigrants who shaped them. There is Little Ethiopia, Thai Town, Little Armenia, Little Bangladesh and Historic Filipinotown.

But neighborhood identity has been more fraught in L.A.’s African American communities, which have long felt disenfranchised by City Hall and ignored by developers and businesses. In 2003, the City Council voted to ban the name “South Central L.A.” from city maps, saying it had become too associated with crime and blight.

The Southside has changed a lot since then, with a black exodus into the suburbs and an influx of Latino immigrants and whites priced out of other parts of L.A.

With the soaring real estate market, there’s a push to preserve Leimert Park as an African American enclave before development transforms the Crenshaw corridor. The construction of a rail line connecting South L.A. to Los Angeles International Airport, plans for a $500-million renovation of nearby Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza, and the recent opening of Kaiser Permanente Baldwin Hills-Crenshaw Medical Offices all stand to accelerate gentrification.

The recent closure and renovation of a park and a city-owned parking lot have left regular visitors and street vendors feeling pushed out. Earlier this month, those tensions bubbled over when members of Africa Town Coalition — an activist group rallying for a name change separate from Hall’s campaign — say they harangued white people listening to a jazz performance and a member was assaulted.

Earlier attempts to etch out a space for black Angelenos have faltered, but some say there’s greater urgency now because of the demographic shift and development boom.

Hall hopes a designation might help merchants attract a larger slice of tourism; last year, 48.3 million tourists visited Los Angeles. A robust commercial center, she said, would push businesses to hire more employees, and the money would flow through the community.

Time has shown that rebranding a neighborhood mostly makes it more inviting to outsiders. Dumbo in Brooklyn and downtown Los Angeles were once drab, but are now hip and less affordable to longtime residents. Some say Leimert Park has its own identity and question the wisdom of linking it with a continent of diverse people, cultures and customs that differ in many ways from the black American experience.

“Little Africa or Africa Town does not resonate strongly with me as an African American,” Leimert Park resident Diane Robertson said after a community meeting to discuss a possible state arts designation for the area. “The bond there was broken so many centuries ago that I don’t feel that connection.”

For decades, African-themed and black-owned shops have been Leimert Park’s primary draw. Residents and merchants have been waiting for years for the completed renovation of the Art Deco Vision Theatre to host regular live performances and bring much-needed foot traffic to a strip that houses a longstanding black bookstore, storefront performance venues, and African importers. Others, however, see a different direction for the area.

They wonder why Leimert Park lacks the restaurants and retail of Westwood Village, which has similar geography. The recent arrival of a bike shop, a contemporary art gallery owned by MacArthur grant recipient Mark Bradford, and a recently opened café could provide a glimpse of where the area is heading: a retail strip that while black-owned includes the kind of stores common in many gentrifying neighborhoods.

“I don’t buy incenses,” said Damon Turner, lifelong Leimert Park resident and co-founder of the Ride On Bike Shop Co-Op. “I don’t wear a dashiki. I grew up in the Nation of Islam so I’m as black as the next man. That don’t have anything to do with trying to get all people to come here, go have lunch and go to the movie and have a glass of wine. That’s what they do in Culver City.”

On a recent trip to Leimert Park Village, Hall purchased a poster of a classic Impala from one of the street vendors. She visited Sika, a shop named after its eccentric owner who sells African imports, to buy a container of his homemade shea butter cream.

“Who knows what a Leimert Park is when you’re traveling?” Hall said, a multicolored beanie covering her white afro. “They want to see an Africa Town or Chinatown.”

Leimert Park is named after the white real estate developer who built the planned community. The name Africatown is also historic. In the late 1800s, dozens of freed slaves from West Africa formed a community called Africatown outside Mobile, Ala., where they spoke their native language and practiced the customs of their homeland. That community is the setting of Zora Neale Hurston’s new book “Barracoon.”

The area Hall and others want to stake claim to is along Crenshaw Boulevard from Stocker Street to Leimert Boulevard and south to Vernon Avenue. Over the years, it has served as a place to mourn when tragedy strikes or to celebrate triumphs like the election of the nation’s first black president.

In 1993, community activist Melva Parhams attempted to designate the same area the African International Village. Those efforts died. As did Hall’s initial attempt six years later.

Hall, known for her work organizing profanity-free open-mic nights with Youths for Positive Alternatives, did not let up. Around 2004, she collected 75 signatures from residents and merchants. Elected officials wrote letters of support, which she still keeps in laminated pages inside a three-ring binder dedicated to Africa Town. Inside it are mock-ups of housing, retail, spruced up buildings and “museums galore” — including one celebrating the civil rights movement she dubbed the Museum of Resilience and Atonement.

“Everybody knows our origins come from Africa,” said Kevin Wharton Price, a leader of the Africa Town Coalition, which is seeking to establish an autonomous community called Africa Town to celebrate black people’s connection to the continent. “And Africa speaks specifically to our experience.”

Over the years, many southside neighborhoods — Central Avenue, Watts, and Leimert Park — claimed to be the center of L.A.’s black life. But the 1992 riots and years of violent crime drove black residents east, leaving many African American strongholds now predominantly Latino. Leimert Park however, remains 70% black.

Hall and her supporters know that re-christening an area won’t halt changing demographics. But “it will give our people something tangible for the community to tie into” and to promote pride in our community, said Ruth Isaacs Hamilton, 60, Hall’s teammate on the project.

While Hall envisions the area as Africa Town, Isaacs Hamilton wants to create a Pan African Arts District. It would encompass the surrounding area and be anchored by Leimert Park Village, renamed as Africa Town.

Price, the activist with Africa Town Coalition, has a national plan to establish Africa Towns in every major metropolis.

In February, community activist Najee Ali collected more than 1,000 signatures in nine days in an effort to rename the commercial thoroughfare in Leimert Park Village from Degnan to Wakanda after the fictional East African nation in the blockbuster “Black Panther.”

“We need to start renaming streets in primarily black communities like Leimert Park that recognize black culture and black pride,” Ali said. “Too often black folks will drive down Adams, Washington and Jefferson [boulevards] and don’t even think these streets are named after former presidents but also former slave owners.”

The city’s formal process for designating a neighborhood requires 500 signatures along with an application that includes a solid pitch for why a name change is merited.

“Sometimes all it takes is two or three people and they will say, we represent for the majority of folk,” said Councilman Herb Wesson, who represents Leimert Park and sits on the committee overseeing neighborhood designation. “The key is you have to build a consensus. With the right group of people, and they go through the right process, then anything is possible.”

None of the groups or individuals have submitted an official petition.

Another group of a dozen or so Leimert Park residents has been exploring an arts designation through the state under the neighborhood’s current name.

But as activists in other parts of Los Angeles have framed art galleries as synonymous with gentrification, such designation has been met with skepticism by some in Leimert Park.

Paula Ricketts, 65, fears art galleries and coffeehouses will hasten development, and she worries buses of white tourists already visiting the neighborhood are a further sign longterm black residents, like herself, could be priced out.

“There is no other black area left in Los Angeles,” said Ricketts, a longtime Leimert Park resident. “Central Avenue is gone. Watts is gone. There’s really isn’t much left.”

Hall believes she must work fast. She said she has to get Africa Town up and running by the 2028 Olympics, when tourists will pack the city.

Years ago, when Hall started her journey to establish an official hub for black Angelenos, she stumbled upon what one writer thought was the African American community’s cultural home.

The corners of Florence and Normandie, the birthplace of 1992 riots. She hopes to see Africa Town in the tourist guide books, and not a place of pain.

“That alone should say, ‘All right, let’s get Africa Town up and going,’” she said.

For more California breaking news, follow @AngelJennings. She can also be reached at [email protected].

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.