California hit its climate goal early — but its biggest source of pollution keeps rising

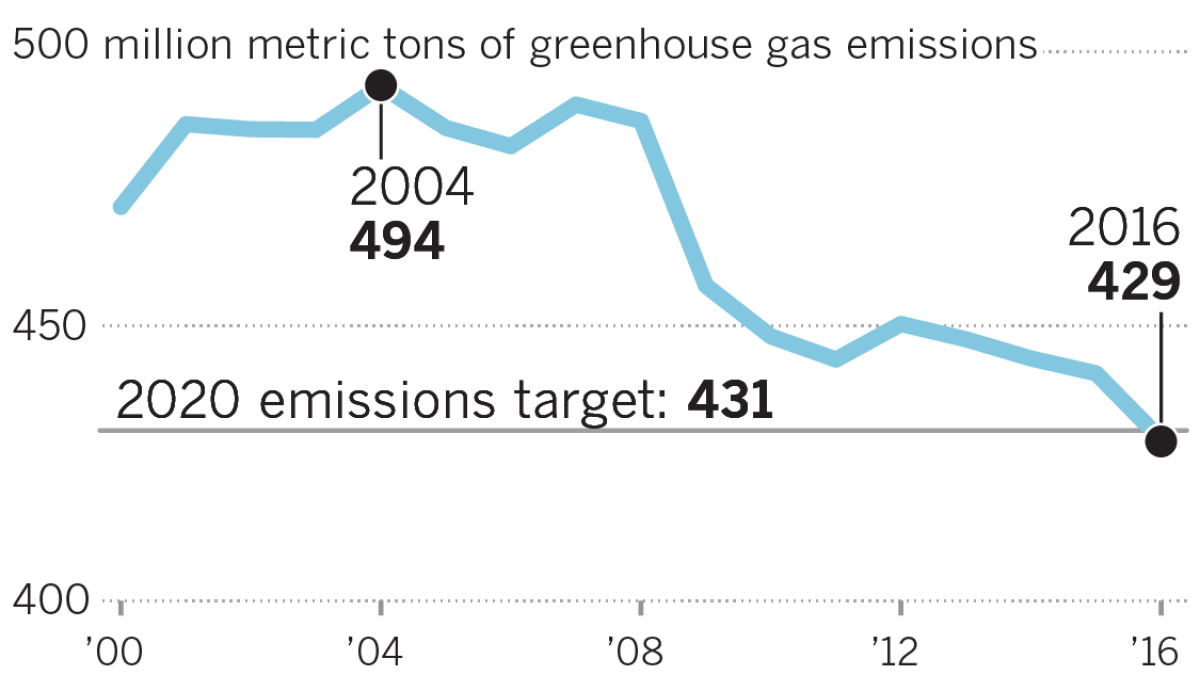

California hit its target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions below 1990 levels four years early, a milestone regulators and environmentalists are cheering as more proof that you can cut pollution while growing the economy.

But a closer look at data released by the state Air Resources Board shows that while emissions from electricity generation in California have plunged, other key industries are flat and transportation pollution is increasing.

Further complicating matters is a Trump administration plan to weaken fuel economy standards and revoke California’s power to set its own, stricter rules — a move that could cause vehicle emissions to rise even more.

The uneven progress shows the big challenges that loom as California advances toward its more ambitious goal: slashing planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions another 40% by 2030.

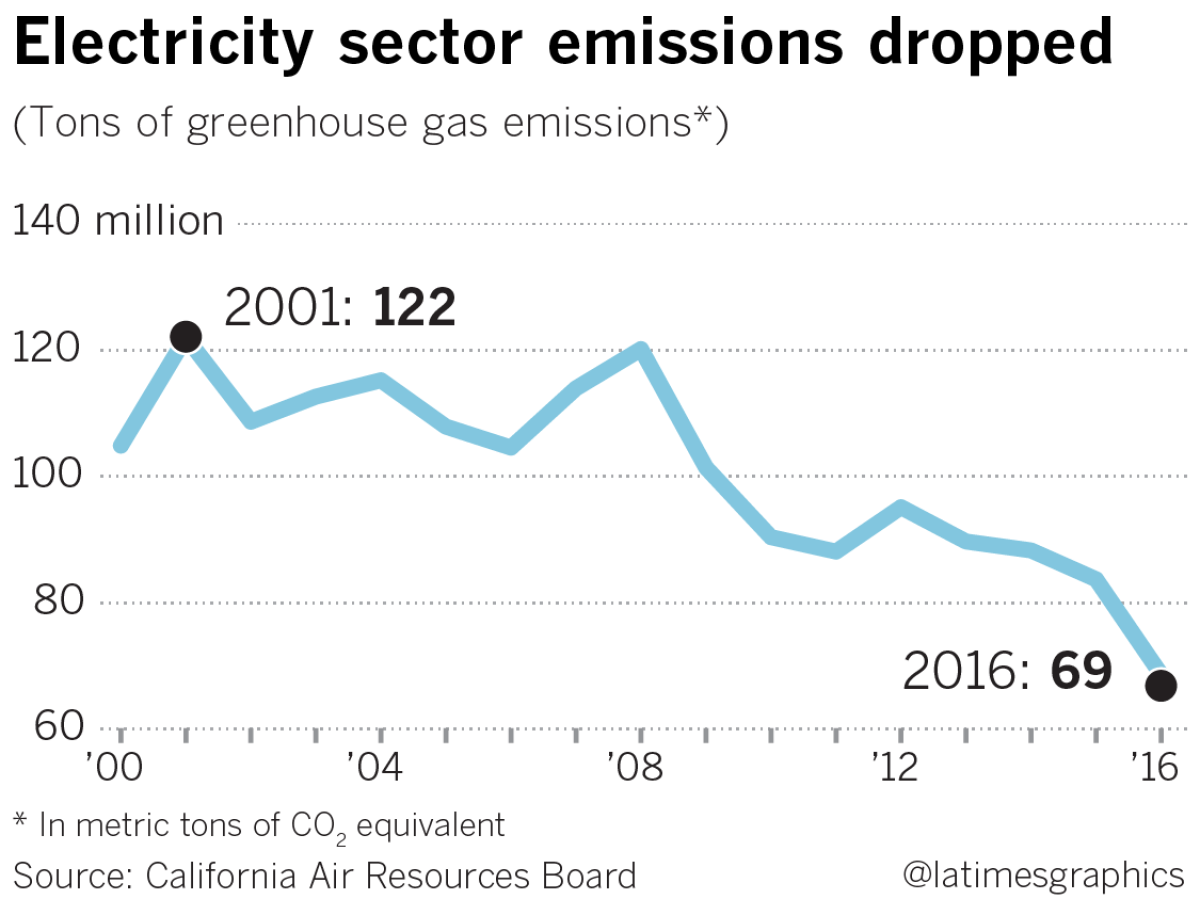

Growth in renewable energy was the main reason California met its 2020 climate goal in 2016, the emissions report released this month shows.

“We’ve seen a substantial increase in solar and wind power, particularly rooftop solar installations,” says Dave Edwards, chief of the Air Resources Board’s greenhouse gas and toxics emissions inventory branch.

Driving the shift is early compliance with the state’s mandate that 33% of electricity come from renewable sources by 2020 and the falling cost of solar panels, which has spurred more commercial and rooftop installation. By 2016, the state was already at 46% renewable electricity. Solar electricity grew 33% in 2016, while natural gas decreased by more than 15%.

California also got an assist from the weather. After five years of punishing drought, rains swelled rivers and generated more hydroelectric power. During drier years, the state relied more on natural gas.

Overall, the growth in renewables combined with waning imports of coal power to send emissions from electricity generation plunging 18% in 2016 compared to 2015.

Now for the downside.

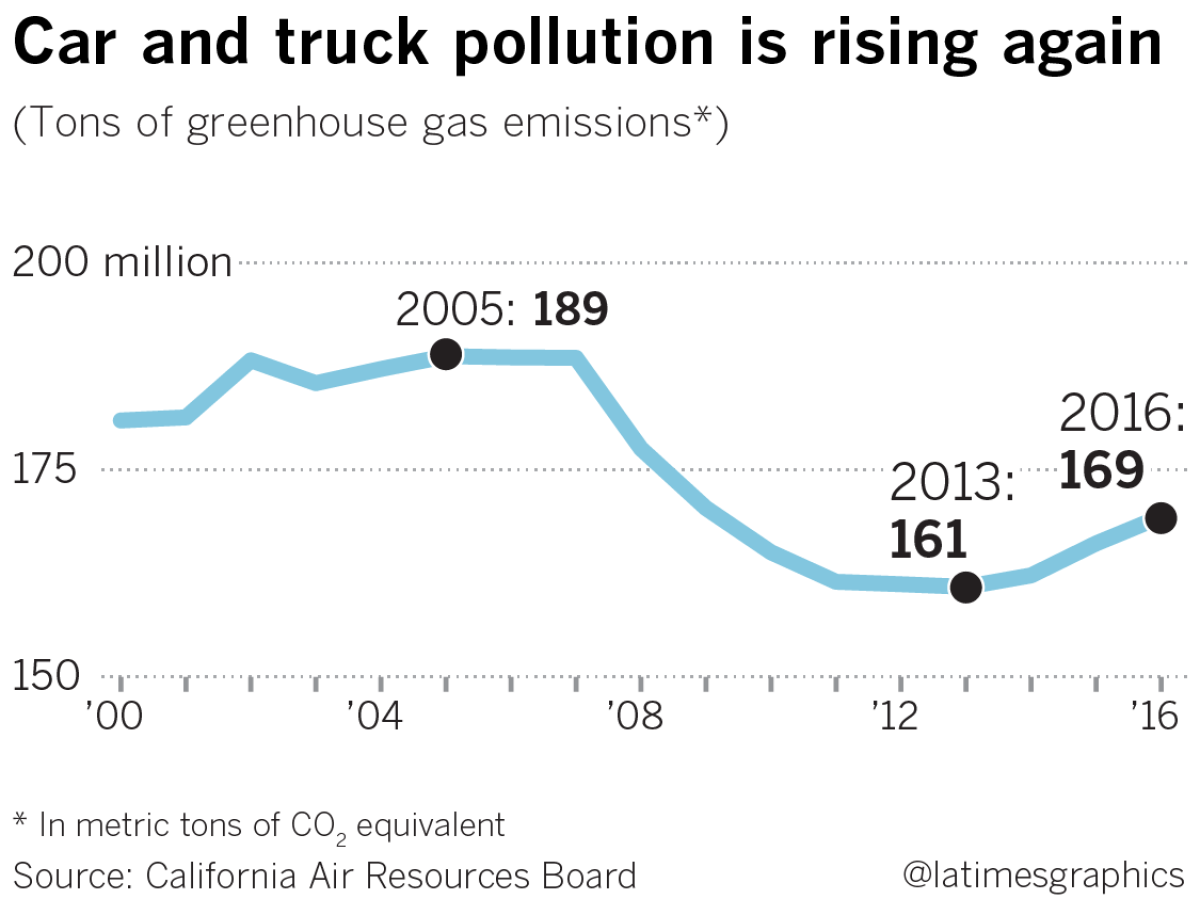

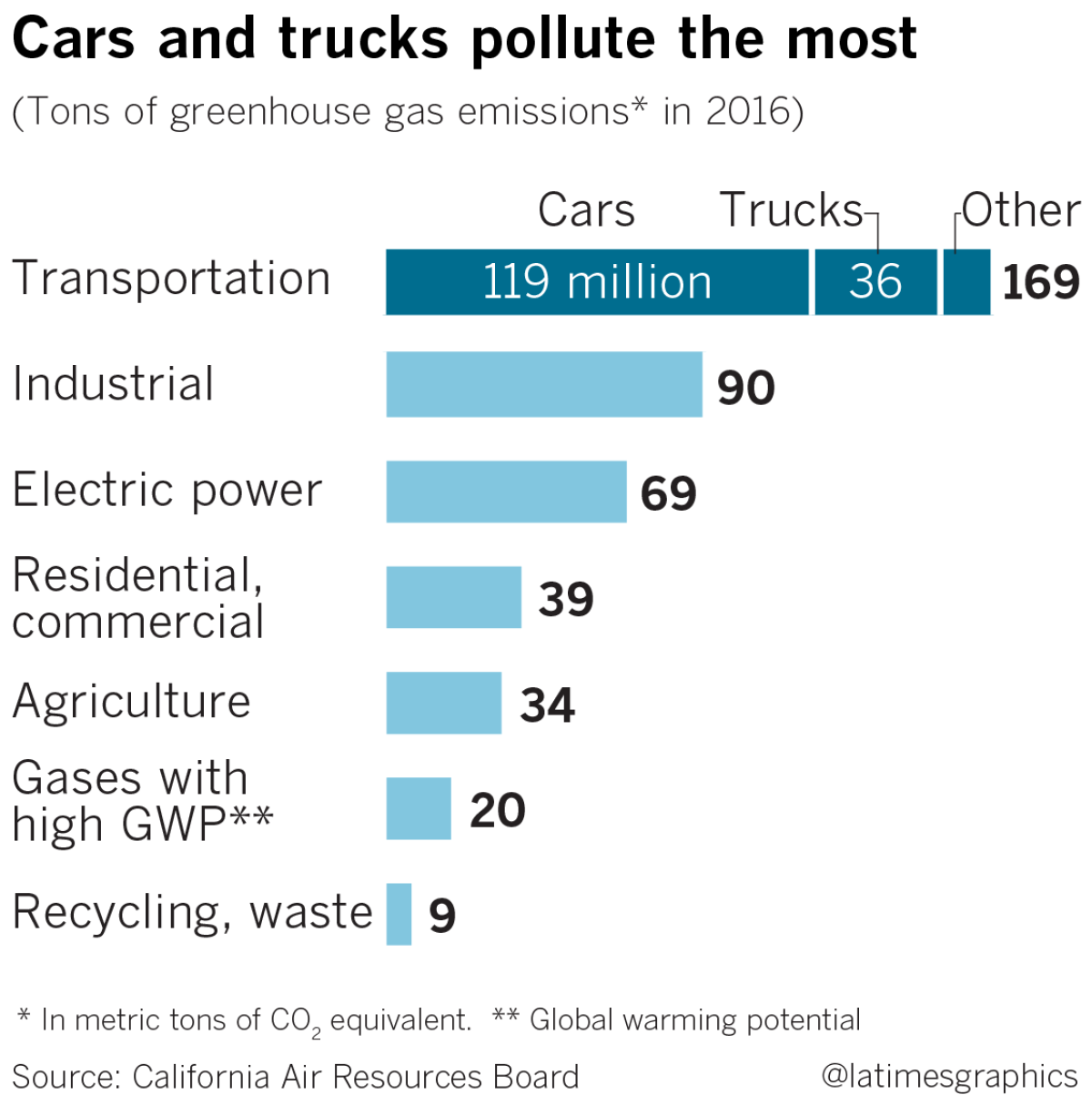

Emissions from cars and trucks, already California’s biggest source of greenhouse gases, have been on the rise for the past few years in step with post-recession economic growth. Increased driving is the main reason why transportation pollution ticked up another 2% in 2016.

“The deep reductions from electric power generation are compensating for lackluster performance in other sectors of the economy, including an uptick in the transportation sector where we know we have our work cut out for us,” said Alex Jackson, senior attorney at the Natural Resources Defense Council who tracks California climate policy.

To blame for the increase in vehicle pollution is a combination of low gas prices, a growing economy, consumers’ preference for roomier, less efficient vehicles and a slower-than-anticipated transition to electric models. Those factors are essentially wiping out gains from the state’s emissions-cutting regulations.

In another impending obstacle, the Trump administration is expected this week to release its plan to scrap aggressive Obama-era fuel economy standards, according to sources familiar with the proposal. The administration’s move would also take away the authority granted to California and other states under the Clean Air Act to continue pursuing those stricter standards.

The rollback would be an enormous hit to the state’s efforts to clean its air and slow global warming by eliminating the current goal of getting cars and SUVs to meet fleet-wide averages of more than 50 miles per gallon by 2025. Instead, gas mileage targets would be frozen in place in 2020.

A drawn-out legal battle is likely. California and other states have already sued the administration to prevent the weakening of clean car rules.

Slashing car and truck pollution is crucial because other key sectors of the economy, such as oil refineries, residential heating and agriculture, saw greenhouse gas emissions remain relatively flat or even rise slightly in 2016.

State regulators say that in itself is a triumph. Pollution from transportation and industry, they contend, would have been much higher without California’s climate change policies, which functioned as a lid keeping emissions in check even as its economy grew.

Air Resources Board officials played down the significance of rising car and truck pollution. Instead they are crediting measures such as cap-and-trade and the low-carbon fuel standard — market-based programs the state is using to push industry to cut pollution and shift to cleaner transportation fuels — with preventing emissions from rising even higher.

“All the indicators we’re looking at are moving in the right direction,” Edwards said. “We think that we’re on the right trajectory right now toward 2030.”

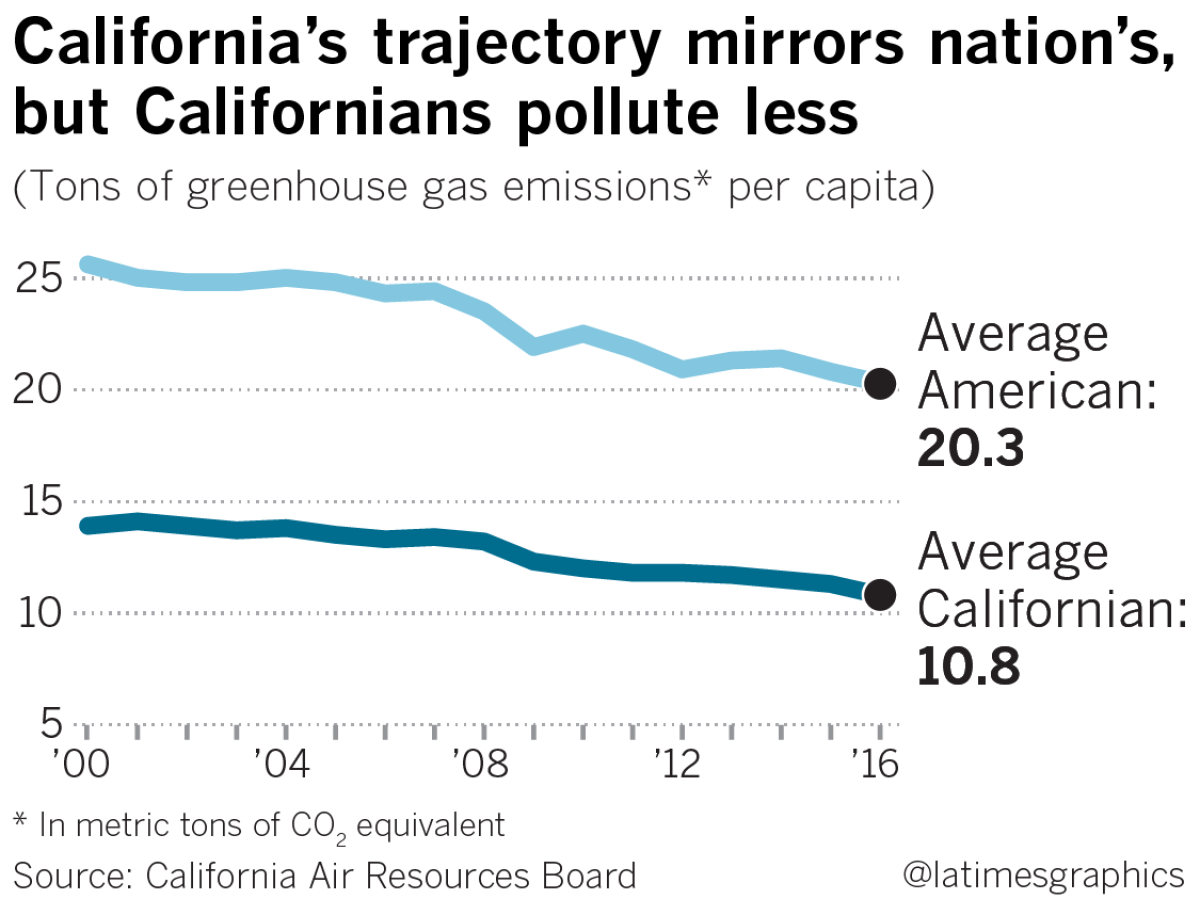

For now, California’s reductions in greenhouse gas emissions remain modest, and are broadly consistent with a nationwide decrease in recent years. The trend across the U.S. is the result of an economic shift: We’re getting less electricity from dirty, coal-fired power plants and more from cheaper, lower-polluting natural gas.

Yet while California’s greenhouse emissions dipped below 1990 levels in 2016, the national rate remained 2.4% above 1990 levels, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

And though California’s electricity grid is powered increasingly by renewables, it was cleaner than the nation’s to begin with. California’s per-capita greenhouse gas emissions today are about half that of the nation as a whole. And they keep dropping, from a peak of 14 metric tons per person in 2001 to 10.8 in 2016.

That was viewed as an obstacle when California adopted its landmark 2006 climate law, AB 32, which enshrined the goal of cutting greenhouse gases below 1990 levels by the year 2020. At the time, industry and other critics argued that California’s relatively clean power grid would make its climate goals painful and prohibitively costly to reach. That fear, regulators and environmentalists say, has now been proven wrong.

To reach its tougher 2030 goal, however, California will have to pick up the pace and roughly double its greenhouse gas reductions. That feat, environmentalists say, will require not only a cleaner electrical grid but a rapid shift to zero-emission vehicles powered by it.

“Looking at the electricity sector 10 years ago, solar in that time went from exotic to conventional,” says Jimmy O’Dea, senior vehicles analyst for the Union of Concerned Scientists. “And that’s where we’re at with electric vehicles going forward. They’re going to go from exotic to conventional in a short period of time.”

Times Staff Writer Evan Halper in Washington, D.C. contributed to this report.

UPDATES:

4:25 p.m., July 23: This article was updated with information on a Trump administration plan to roll back vehicle fuel economy standards.

This article was originally published at 3 a.m. on July 22.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.