Adelanto cuts ties to troubled ICE detention center — and removes a layer of oversight

Adelanto city officials are parting ways with the federal government and a private prison company, ending the high desert city’s role in overseeing the management of California’s largest immigrant detention facility.

It’s the latest in a string of similar decisions by local governments to terminate their contracts with Immigration and Customs Enforcement over immigrant detention, bowing to the pressures of state laws that limit the interaction between local officials and federal immigration enforcement agents.

For the record:

9:00 a.m. April 8, 2019A previous version of this article stated that the Orange County Sheriff’s Department will stop holding ICE detainees on Aug. 1, 2020. The department will change its policy this August.

But because of the complexities of contract law, these moves could actually end up expanding immigrant detention. By withdrawing from their contracts, and no longer serving as go-betweens, California municipalities could make it easier for ICE to go directly into business with private prison companies and sidestep limits imposed by state law on expanding detention facilities.

In letters dated March 27 to ICE and the private prison company GEO Group, City Manager Jessie Flores announced that Adelanto’s contract with both entities will end in 90 days.

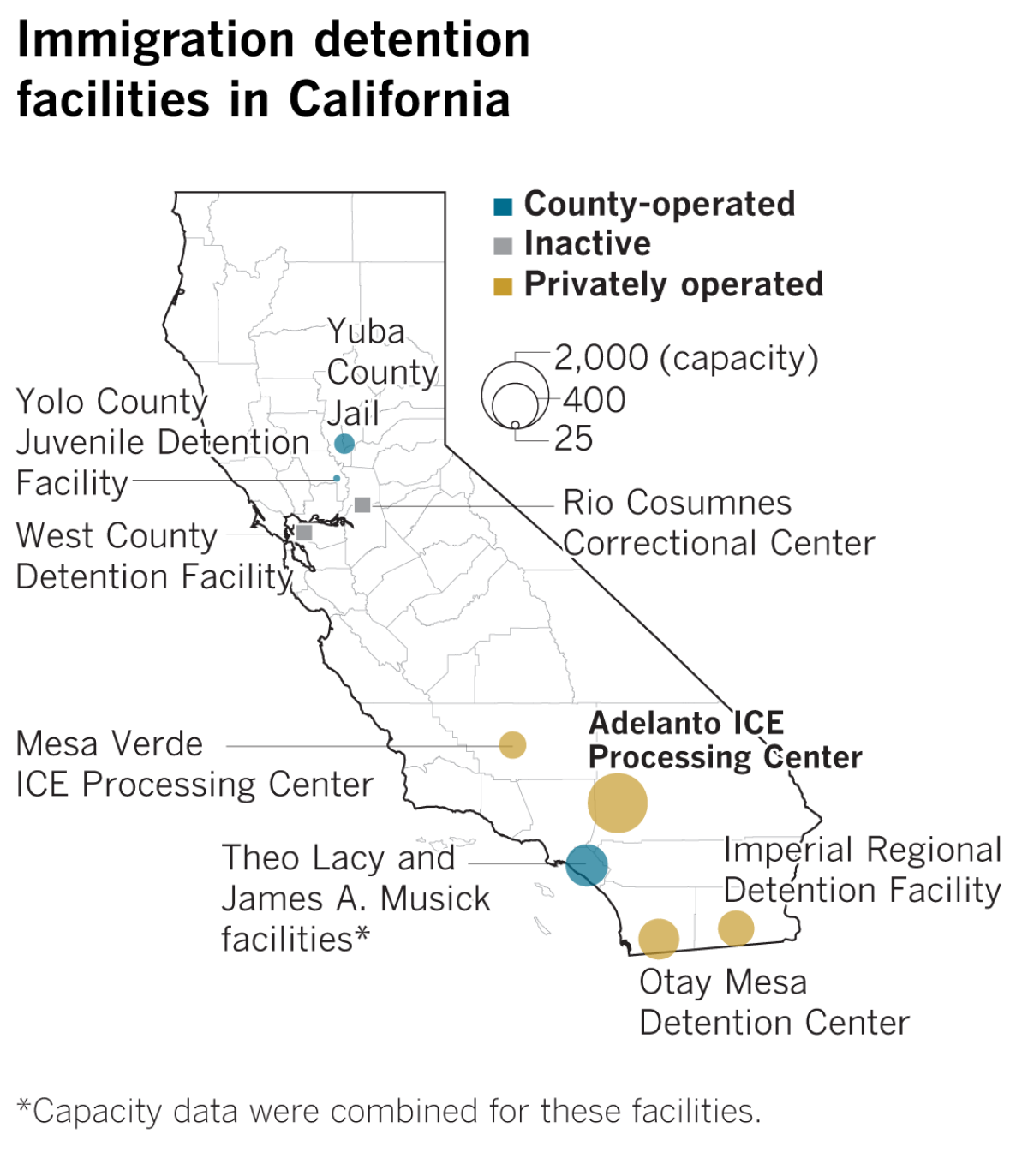

Florida-based GEO Group runs 12 other immigrant detention facilities throughout the country. With nearly 2,000 beds, the Adelanto ICE Processing Center in San Bernardino County is one of its largest. Detainees are held for civil immigration-related offenses, not for criminal prosecution.

The facility has been widely criticized for a number of problems, including inadequate medical care and serious safety violations. A Department of Homeland Security inspector general’s report made public last year disclosed that a Nicaraguan man had died there, found hanging in his cell from his bed sheets, and that two other detainees had tried to hang themselves.

Detainees routinely hold hunger strikes to protest conditions. A recent report by the California state auditor found that Adelanto has failed to properly oversee the management of the facility.

Federal regulations require ICE to conduct a competitive public bidding process before awarding a contract to a company interested in managing the daily operations of a detention facility. But most ICE facilities operate the way that Adelanto has, under intergovernmental service agreements.

The local governments serve as administrative vehicles, either passing funds between ICE and private prison companies or accepting funds to hold immigrants in local jails. The agreements allow ICE to quickly expand bed space instead of constructing new federal government-owned facilities.

Critics have argued that using local governments as go-betweens allows ICE to circumvent the lengthy public bidding process and avoid responsibility in the event of any abuse or harm to detainees, including fatalities.

As immigrants have been detained in record numbers, the Trump administration has sought to expand detention capacity. In early February, ICE detained an average of 49,000 people a day, up from about 34,000 a day in 2012.

Just ahead of his trip Friday to the southern border in California, Trump withdrew his nominee to run ICE because he wanted the agency to move in a “tougher” direction.

Until last year, there were 10 facilities in California housing immigrants in deportation proceedings for extended periods. By this summer, the state will be down to six. Officials in Sacramento and Contra Costa counties decided last June and July, respectively, to stop holding immigrants in their jails for deportation. And last month, the Orange County Sheriff’s Department announced that it will stop holding ICE detainees in the James A. Musick and Theo Lacy facilities starting in August.

The move in Adelanto follows a similar contract termination in McFarland, which oversaw the Mesa Verde ICE Processing Center in Bakersfield until last month. ICE cited “unusual and compelling urgency” in a notice explaining its justification for allowing GEO Group to continue operating the 400-bed center for another year, without McFarland’s involvement, while it prepares to conduct a public bidding process.

A pair of California laws passed in 2017 aimed to block the expansion of immigrant detention facilities in the state by prohibiting local governments from establishing new contracts with for-profit prison companies and ICE, or expanding existing ones.

In a statement, ICE spokeswoman Lori Haley said the agency was exploring all options to keep its facilities open. “However, ICE does operate a national system of detention bed space and will house detainees in other facilities as needed,” she said.

Adelanto’s City Manager Flores, Mayor Gabriel Reyes and representatives of GEO Group did not respond to requests for comment.

But Flores told the San Bernardino Sun that his decision to end the contract was based on budgetary constraints preventing the city from being able to adequately oversee the facility. The decision didn’t require a city council vote, but Flores asked council members for their input last week during a closed session.

Mayor Pro Tem Stevevonna Evans said she was the only one on the five-member council to disagree with the move. Evans, who was elected last November, said she was concerned that, by ending its contract with GEO Group and ICE, the city would forfeit its ability to monitor the troubled facility.

Evans said Flores’ idea to cancel the contract goes back to late February, when she walked in on a meeting between him and GEO Group Chief Executive George Zoley over the possibility of ending the contract. She said they explained that ending the contract would alleviate the city of potential future litigation.

Evans said she had wanted to establish an oversight committee for the detention facility.

At that February meeting, Evans said, Zoley also explained that state law prohibited the company from expanding operations — unless the city backed out of the contract.

In fiscal year 2017, Adelanto transferred more than $71 million in payments from ICE to GEO Group. In return, GEO has paid the city a yearly fee of about $1 million to oversee the distributions. Evans said that Zoley assured city leaders that they would continue receiving payment even after they ended the contract.

City leaders, including Evans, met again with Zoley before last week’s closed-session council meeting. She asked if the council could put the decision question on the calendar and allow for public comment. But the others appeared to be in a hurry, she said.

“I think there’s a way bigger picture that the council and our city manager aren’t seeing,” she said. “For me, it was too many red flags.”

Flores told inspectors with the state auditor’s office that the only involvement the city has with the facility’s operation is to sign monthly invoices from GEO and then to transfer federal funds the city receives when ICE pays the invoices. Adelanto leaders said they were unaware of previous inspection reports detailing serious problems at the facility.

Liz Martinez of Freedom for Immigrants, a nonprofit that advocates for the elimination of immigrant detention, said she was alarmed by what she saw as an attempt by GEO Group to circumvent state law in keeping the Adelanto center open. Martinez said she worries what could happen if the company contracts directly with ICE to keep the facility open.

“For so long, cities like Adelanto and McFarland were part of the system — they were complicit in the system,” she said. “They can’t just wash their hands of this by terminating the ICE agreement. If anything, they have a greater responsibility to know what’s happening there.”

Emily Ryo, law and sociology professor at USC who studies immigrant detention, said she wouldn’t be surprised if GEO Group contracts directly with ICE to keep the Adelanto facility open. State law can’t block the expansion of detention space under that type of contract.

“It has sort of transferred more power to the private prison industry in a way that I think wasn’t intended,” she said of the law. And without a local government as the middleman, she added, “it’s dangerous in the sense that we know private prison companies are much less transparent and accountable to the public.”

“To the extent that ICE is desperate to have these facilities stay open,” she said, “these private prison companies are going to have a lot of leverage.”

[email protected] | Twitter: @andreamcastillo

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.