That Mexican school that collapsed? It was a brittle concrete building — a type known to be vulnerable in quakes

To structural engineers, it’s no mystery why the earthquake in Mexico this week turned a school into a death trap: The building was made of brittle concrete.

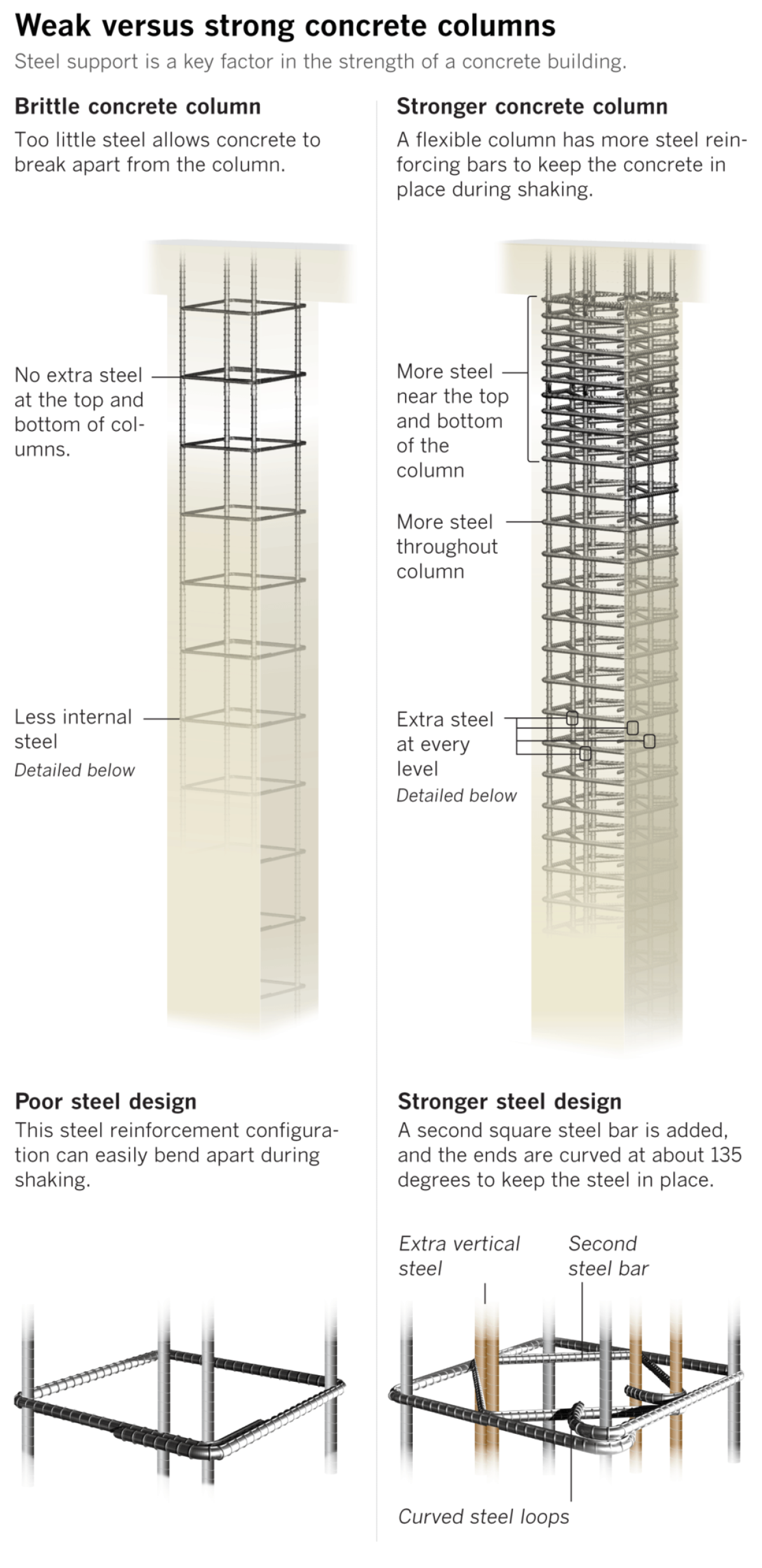

Such buildings don’t have enough steel reinforcing bars, known as rebar, which are encased in the concrete and act as a cage, allowing columns to crack and bend without crumbling.

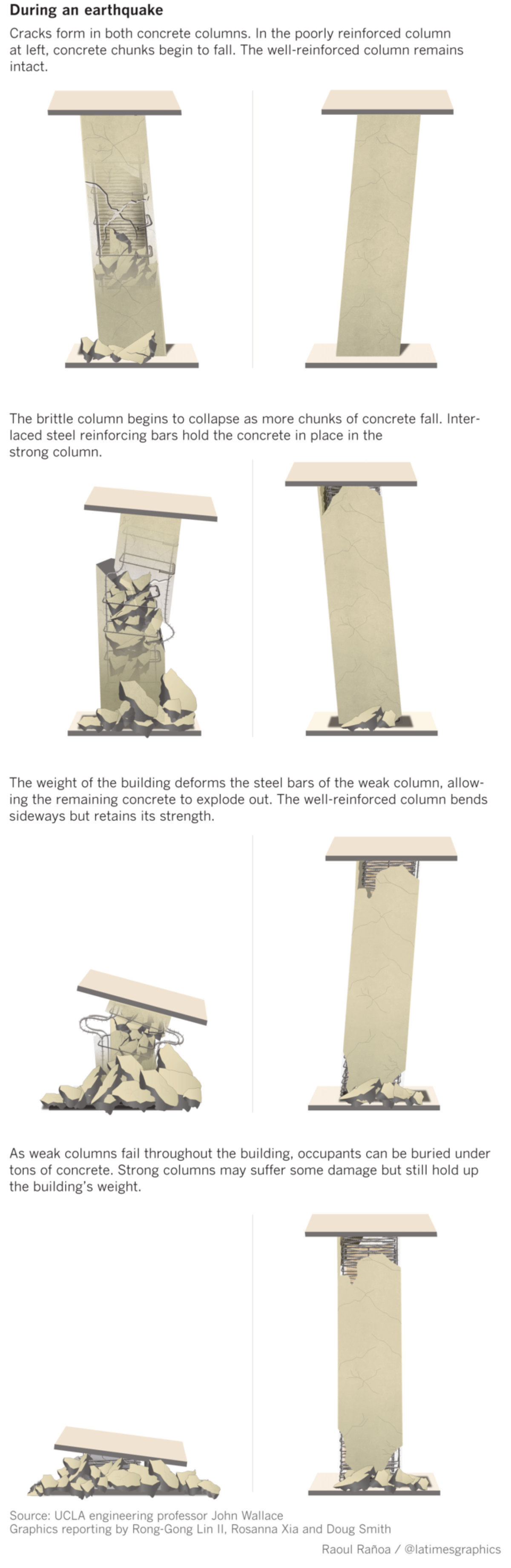

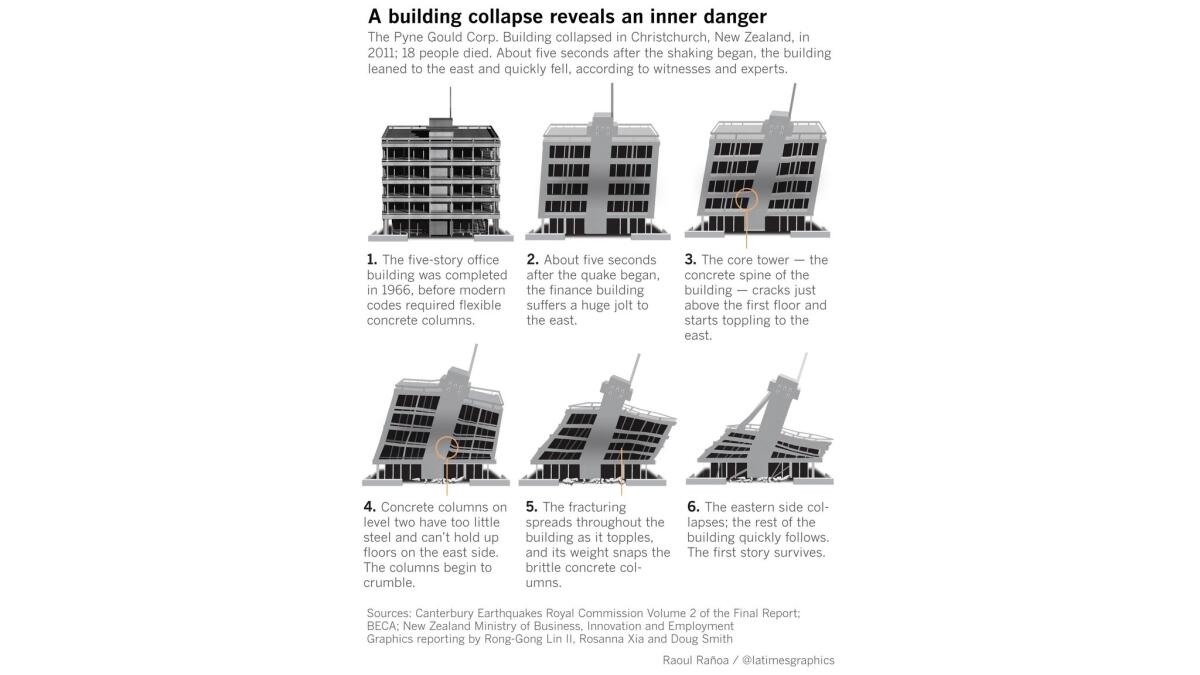

Unlike steel or wood, concrete is non-ductile — it breaks before it bends. In an earthquake, concrete not sufficiently caged in steel can fall out, first piece by piece, then in catastrophic bursts that can bring down a building.

A concrete column without adequate reinforcement can snap like a piece of chalk.

In the case of Mexico’s City private Enrique Rebsamen school, where the bodies of 21 children and four adults have been recovered, a photograph published by the Los Angeles Times shows a concrete column leaning at a severe angle.

That’s a sign that when the structure was built, too little steel rebar was used to keep the concrete columns in place between the floors during an earthquake, said Kit Miyamoto, a structural engineer and member of the California Seismic Safety Commission.

It’s like using a too-short screw to keep a table attached to its legs. “If the screw is shallow, it will fall out. You need a deep screw into the table top,” Miyamoto said.

The photo also shows a single concrete column broken in half.

“It breaks in a clean break, as opposed to a bending break,” said structural engineer David Cocke, vice president of the Earthquake Engineering Research Institute.

“When they break in half like that, you’ve lost it all,” he said.

Had there been more steel rebar to act as a cage to the concrete, the column most likely would have been flexible enough to ride out the side-to-side motions in an earthquake, he said.

For decades, architects and engineers worldwide built concrete buildings this way, not realizing the risk that design carried in the event of an earthquake.

That all changed after the magnitude 6.6 Sylmar earthquake of 1971.

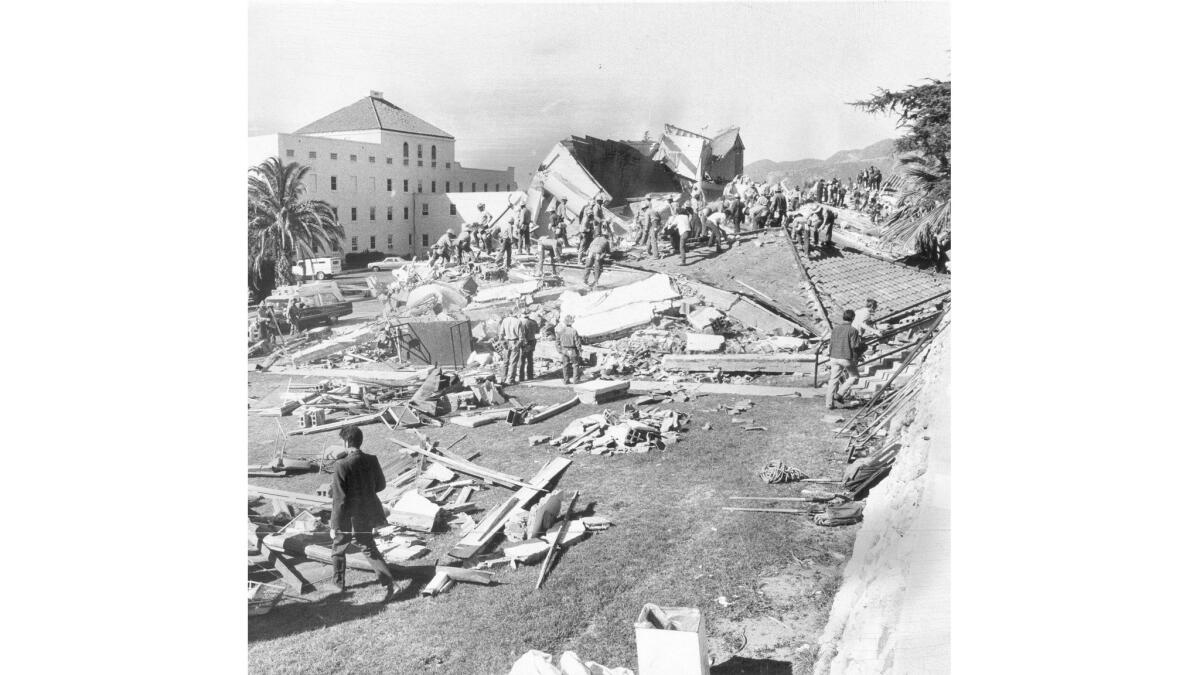

Seismic experts were alarmed when a newly opened five-story building Olive View Medical Center lurched sideways as some of its first-floor columns broke and three concrete stairwells toppled. A two-story psychiatric building collapsed. In all, three people died.

Older concrete buildings, too, suffered major damage. Two concrete structures at the 46-year-old Veterans Administration Hospital in San Fernando shattered. The three-story buildings pancaked when the concrete crumbled, leaving the red tile roof smashed on the ground. A total of 49 people were killed.

That earthquake eventually led to new building codes requiring more steel inside concrete columns.

But generally speaking, new building rules don’t apply to old buildings.

Los Angeles in 2015 became one of the first cities in California to launch an effort to retrofit brittle concrete buildings, setting a 25-year deadline for retrofitting once an owner is instructed to conduct a seismic safety evaluation.

Santa Monica and West Hollywood passed similar laws this year, but most other cities in California do not have them.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.