Defectors Recount Lives of Hard Work, Punishment

Doris Braine says the transformation of her Patty Jo was heartbreaking.

“It was,” she said, “like my darling daughter had died.”

Before Patty Jo went to work for the Church of Scientology at the age of 20, she had been “fun and pretty and a joy to be with,” recalled her 72-year-old mother. “Suddenly, she became a totally different person, shooting fire from her eyes.”

There were those hateful looks, and the dozens of letters that Patty Jo returned unopened. For two years, she would not even speak to her mother, who had criticized Scientology and refused to hand over $2,000 for church courses.

And Patty Jo had taken to calling Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard her father.

“I would cry all the time,” recalled Braine, a retired college dean. “I had to psych myself up to go to work, be charming and do a good job. But all day long I thought about her. I prayed my head off that someday she would be able to get out of it.

“It took 15 years, but I think it was worth every prayer I said.”

In 1982, Patricia Braine left Scientology, disillusioned with the church and disappointed with herself for succumbing to an environment that, she said, twisted her thinking and isolated her from a world she had hoped to make better.

Scientology, she said, “promises you euphoria but ends up taking your body, heart, mind, soul and family. . . . We were so brainwashed to believe that what we were doing was good for mankind that we were willing to put up with the worst conditions.”

Over the years, defecting Scientologists have come forward with similar accounts of how their lives and personalities were upended after they joined the church’s huge staff. They say the organization promised spiritual liberation but delivered subjugation.

In interviews and public records, former staffers have said they were alienated from society, stripped of familiar beliefs, punished for aberrant behavior, rewarded for conformity and worked beyond exhaustion to meet ever-escalating productivity quotas.

“Slave labor” is how Canadian authorities in 1984 described the Scientology work force.

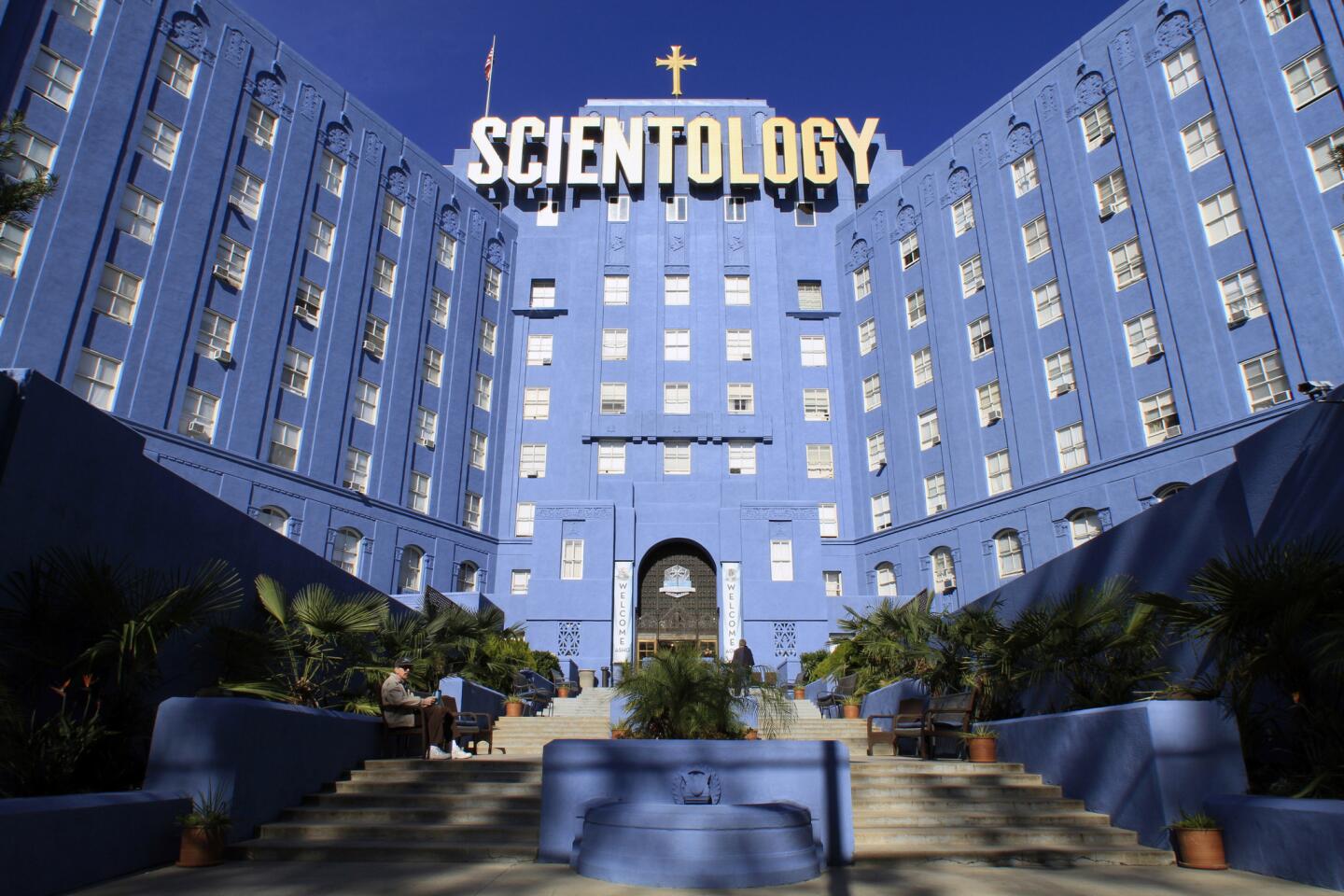

Worldwide, there are nearly 12,000 church staff members, many of whom are in Los Angeles, one of the organization’s largest strongholds. They have kept Scientology afloat through a turbulent history that, arguably, would have sunk any other newly emerging religion.

Day and night they labor single-mindedly at jobs ranging from the meaningful to the menial. Some work in administrative areas such as promotion, legal affairs, finance, public relations and fund raising. Thousands of others deliver the church’s religious programs. Still others proselytize on city sidewalks, sell books and wash dishes.

Scientology spokesmen insist that the staff is treated well and not exploited. They say that the detractors simply lacked the devotion to advance the religion’s aims and the morality to abide by its high ethical standards.

Current staff members say their lifestyle is no more unusual or harsh than that of a monk. Joining the Scientology staff, they say, was the supreme expression of their devotion to create, in Hubbard’s words, “a civilization without insanity, without criminals and without war, where the able can prosper and honest beings can have rights.”

The elite of Scientology’s workers, at least 3,000 of them, belong to a zealous faction known as the Sea Organization and are given room, board and a small weekly allowance.

They sign contracts to serve Scientology in this and future lifetimes--for a billion years. Their motto is: “We come back.”

Dressed in mock navy uniforms adorned with ribbons, they bark orders with a clipped, military cadence. They hold ranks such as captain, lieutenant and ensign. Officers, including women, are addressed as “Sir.”

Hubbard called himself “The Commodore,” a reflection of his infatuation with the U.S. Navy. “The Sea Org is a very tough outfit,” he once said. “It’s no walk in the park. . . . We are short-tempered, but we do our job.”

Scientology staffers enter a clannish world of authoritarian rules and discipline based on Hubbard writings. His works govern every detail of the operation, from how to disseminate his teachings to how to cook baby food.

When staffers observe transgressions of Hubbard’s dictums, they are required to inform on each other. The church says “knowledge reports” help the organization correct problems and ensure a high standard of operation. But critics contend that the practice works to stifle expressions of discontent or doubts about the church, even between husbands and wives.

To break the group’s rules or fall below work quotas can subject even top Scientologists to grueling interrogations on a lie detector-type device called the E-meter, and perhaps land them in the Rehabilitation Project Force, or RPF.

The Rev. Ken Hoden, a church spokesman in Los Angeles, once described the RPF like this: “You just do some grounds work for a few weeks. That’s all.”

Others, however, have called it in hindsight the most degrading ordeal of their lives--although one that they believed at the time was leading them to spiritual salvation.

RPFers, as they are called, are separated from their family and friends for days, weeks, months or even longer. They cannot speak unless spoken to, they run wherever they go and they wear armbands to denote their lowly condition.

The RPF provides the church with a pool of labor to perform building maintenance, pull weeds, haul garbage, clean toilets or do anything else church executives deem necessary for redemption.

Former Sea Organization member Hana Eltringham Whitfield said in an affidavit that she once saw an RPF work crew eating like “unkempt convicts,” digging their hands into a large communal pot of food because there was no cutlery or plates.

“The Church of Scientology, which was dedicated to saving the planet from insanity, had succeeded in turning these human beings into savages,” said Whitfield.

Bill Franks, the church’s former international executive director, said that he once lived in a crowded garage for seven months while assigned to the RPF.

“We were indoctrinated on a continuous, daily basis that we were suppressive people, that we were anti-social people, that we were criminals,” said Franks, who had a falling out with the church in the early 1980s. He was accused by senior Scientologists of engineering a coup to wrest control of the church from them.

The Church of Scientology says the RPF was established in 1974 so that errant Sea Organization members would have a place to both work and study Hubbard’s writings without distractions or substantive duties.

But Hubbard’s former public relations officer, Laurel Sullivan, testified in a Scientology lawsuit that Hubbard told her the RPF was created because “he wanted certain people segregated” whom he believed were “against him and against his instructions and against Scientology.”

In Scientology, a staff member is evaluated based on his or her productivity. Hubbard made it clear in a 1964 directive that there is no excuse--short of death--for missing work.

“If a staff member’s breath can be detected on a mirror,” Hubbard said, “he or she can do his or her job.”

Measuring weekly productivity, Hubbard said, eliminates personality considerations from staff evaluations. Critics, however, say the system is dehumanizing.

“There is no time for anything else, for compassion, for talking or going out,” said Travers Harris, who left the Sea Organization 1986 after nearly 14 years. “The only communication is about work. When work is finished you are too tired (and) you have to go to bed.”

Several years ago, some branches of the church initiated a program to boost productivity even higher.

Under the so-called Team Share Program, staffers who repeatedly failed in their jobs could be exiled to cramped living quarters called “pigs berthing” and fed only rice and beans. Those who kept their productivity up would be afforded special privileges and the distinction of wearing a silver star.

Staffers become so consumed by their jobs that their children sometimes get lost in the shuffle, according to former staff members who had youngsters and those who cared for them.

At best, they say, children see their parents one hour a day at dinner and perhaps late in the evening. Sometimes, according to ex-staffers, youngsters have gone for days without a visit from their parents, who believe that their work for the group is transcendent.

In 1984, a British justice cited the case of a staff member who left her job to seek medical help for a daughter who had broken her arm.

“She was directed to work all night as a penalty,” the justice noted.

He recounted the case of another woman who refused to take a church job that would have separated her from her daughter for two months.

“She was shouted at and abused because she put the care of her child first,” the justice wrote in connection with a child custody battle between a father who was a Scientologist and a mother who had defected. The mother was awarded custody.

Former staff members say they tolerated the harsh conditions for many reasons. They say they were captives both of their dreams of creating an enlightened world through Scientology and of their fears of leaving the organization.

Staff members are continuously told that there is no safe refuge for them outside the group because society is a breeding ground for criminals, the insane and people too ignorant to see that Scientology is the answer to mankind’s problems.

In the church, non-Scientologists are derisively called “wogs,” defined by Hubbard as “a common ordinary run-of-the-mill garden variety humanoid. . . . Somebody who isn’t even trying.”

A recruitment flyer for a school run by Scientologists exemplifies this mind-set:

“If you turn your kids over to the enemy all day for 12-15 years, which side do you think they will come out on?” the flyer asks rhetorically. The enemy, in this case, is public education.

The organization’s fear of hostile outside influences is so institutionalized that potential staff members are grilled about whether they are government agents or reporters or whether they harbor critical thoughts of Hubbard. Their answers are monitored on the E-meter.

Security around church buildings is elaborate and sophisticated. Remote cameras sweep the streets outside. Scientologists with walkie-talkies scout the perimeters.

In time, the staff member’s world orbits ever more tightly around one man--Hubbard.

“You finally are to the point where you do not examine, logically, Scientology,” said former Scientologist Vicki Aznaran, who until two years ago was one of the most powerful figures in the church and is now locked in litigation with Scientology.

“You are cut off from anything that might give you another viewpoint,” she said.

Some stay because they fear calamity will befall them if they are denied church courses they have been told are vital to spiritual and physical stability.

Former Sea Organization member Janie Peterson, for one, once testified that she was “so indoctrinated into Scientology that I felt . . . I would die” upon leaving.

Other former members said they felt trapped by the church’s “freeloader debt” policy.

Many Scientologists join the staff as a way to obtain the church’s expensive services for free. But should they leave before the expiration of their employment contracts--ranging from two years to 1 billion years--they must pay for the programs they had received at no cost. This “freeloader debt” can reach thousands of dollars.

And on top of all this is the haunting fear that they will be ostracized by family and friends for shunning the religion.

“For those like myself who had been in Scientology for years, Scientology was our entire life, our friendships, our work, our home,” said ex-Sea Organization member Whitfield, who spent nearly two decades on the staff. “The organization had made us grow so entirely dependent on it, it was almost inconceivable to leave.

“After all, we had no job skills, no jobs and we believed we would be immediately hit with thousands of dollars of freeloader debt.”

Whitfield said that she, like others, defected after reaching the conclusion that the church seemed “only interested in controlling” its members.

“I have looked back and said to myself, ‘What an indoctrinated fool I was. What a fool.’ ”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.