Shoring Up Its Religious Profile

Since its founding some 35 years ago by the late science fiction writer L. Ron Hubbard, Scientology has worked hard to shore up its religious profile for the public, the courts and the Internal Revenue Service.

In the old days, for example, those who purchased Hubbard’s Scientology courses were called “students.” Today, they are “parishioners.” The group’s “franchises” have become “missions.” And Hubbard’s teachings, formerly his “courses,” now are described as sacred scriptures.

The word “Dianetics” was even redefined to give it a spiritual twist. For years, Hubbard said it meant “through the mind.” The new definition: “through the soul.”

Canadian authorities learned firsthand how far Scientologists would go to maintain a religious aura.

According to police documents disclosed in 1984, an undercover officer who infiltrated Scientology’s Toronto outpost during an investigation of its activities was asked by a church official to don a “white collar so that someone in the (organization) looked like a minister.”

For three decades, critics have accused Scientology of assuming the mantle of religion to shield itself from government inquiries and taxes.

“To some, this seems mere opportunism,” Hubbard said of Scientology’s religious conversion in a 1954 communique to his followers. “To some it would seem that Scientology is simply making itself bulletproof in the eyes of the law. . . .”

But, Hubbard insisted, religion is “basically a philosophic teaching designed to better the civilization into which it is taught. . . . A Scientologist has a better right to call himself a priest, a minister, a missionary, a doctor of divinity, a faith healer or a preacher than any other man who bears the insignia of religion of the Western World.”

Joseph Yanny, a Los Angeles attorney who represented the church until he had a bitter falling out with the group in 1987, said Scientology portrays itself as a religion only where it is expedient to do so--such as in the U.S., where tax laws favor religious organizations.

In Israel and many parts of Latin America, where there is either a state religion or a prohibition against religious organizations owning property, Yanny said Scientology claims to be a philosophical society.

In the beginning, Hubbard toyed with different ways to promote his creation.

For a time, he called it “the only successfully validated psychotherapy in the world.” To those who completed his courses, he offered “certification” as a “Freudian psychoanalyst.”

He also described it as a “precision science” that required no faith or beliefs to produce “completely predictable results” of higher intelligence and better health. Hubbard bestowed upon its practitioners the title “doctor of Scientology.”

This characterization, however, landed him in trouble with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and a federal judge, who concluded in 1971 that Hubbard was making false medical claims and had employed “skillful propaganda to make Scientology . . . attractive in many varied, often inconsistent wrappings.”

The judge said, however, that if claims about Scientology were advanced in a purely spiritual context, they would be beyond the government’s reach because of protections afforded religions under the First Amendment.

In the United States, it is easy to become a church, no matter how unconventional--you just say it is so. The hard part may come in keeping tax-exempt status, as Scientology has learned.

The U.S. government is constitutionally barred from determining what is and what is not a religion. But, under the law, there is no guaranteed right to tax exemption. The IRS can make a church pay taxes if it fails to meet criteria established by the agency.

A tax-exempt religion may not, for example, operate primarily for business purposes, commit crimes, engage in partisan politics or enrich private individuals. It should, among other things, have a formal doctrine, ordained ministers, religious services, sincerely held beliefs and an established place of worship.

In 1967, the Church of Scientology of California was stripped of its tax-exempt status by the IRS, an action the church considered unlawful and thus ignored. The IRS, in turn, undertook a mammoth audit of the church for the years 1970 through 1974.

So began Scientology’s most sweeping religious make-over.

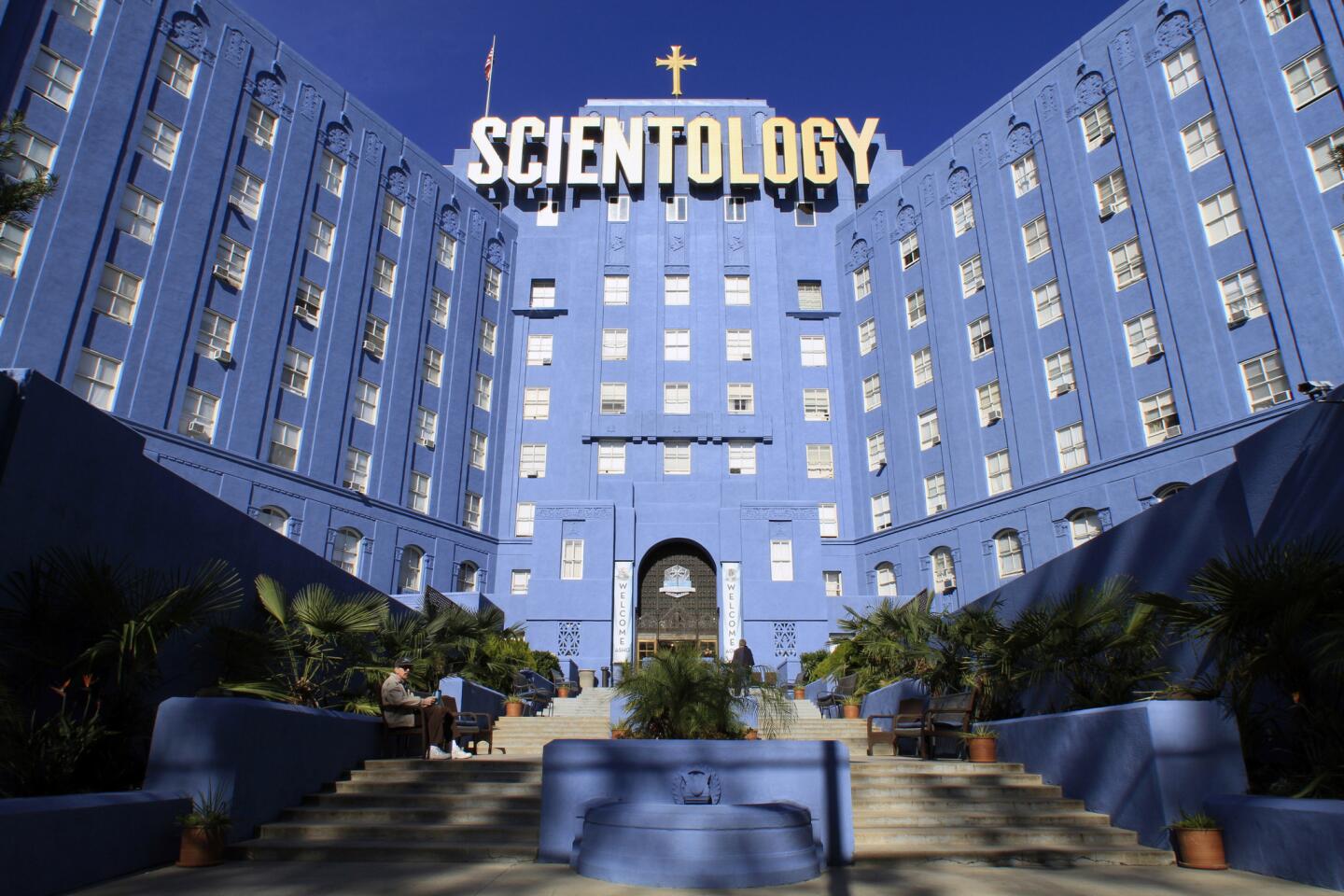

Among other things, Scientology ministers (formerly “counselors”) started to wear white collars, dark suits and silver crosses.

Sunday services were mandated and chapels were ordered erected in Scientology buildings. It was made a punishable offense for a staffer to omit from church literature the notation that Scientology is a “religious philosophy.”

Many of the changes flowed from a flurry of “religious image” directives issued by high-level Scientology executives. One policy put it bluntly: “Visual evidences that Scientology is a religion are mandatory.”

None of this, however, convinced the IRS, which assessed the church more than $1 million in back taxes for the years 1970 through 1972. Scientology appealed to the U.S. Tax Court, where, in 1984, it was handed one of the worst financial and public relations disasters in its history.

In a blistering opinion, the court backed the IRS and said the Church of Scientology of California had “made a business out of selling religion,” had diverted millions of dollars to Hubbard and his family and had “conspired for almost a decade to defraud the United States Government by impeding the IRS.”

The church lost again when it took the case before the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco and the U.S. Supreme Court let the lower-court decision stand.

Stripped of its tax-exempt status, Scientology executives turned the Church of Scientology of California into a virtual shell.

Once called the “Mother Church,” it no longer controls the Scientology empire and does not serve as the chief depository for church funds.

It has been replaced by a number of new organizations that Scientology executives maintain are religious and tax exempt. But, once again, the IRS has disagreed, ruling that the new organizations are still operating in a commercial manner.

Scientology is appealing the IRS decision in the courts.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.