Theater camp helps keep the Spanish in Latino-heritage families

Elena Versage has something to say, but the words just won’t come out.

“Dime,” her teacher urges. “Tell me.”

The 7-year-old looks to the floor and wrings her hands. “I can’t,” she whispers. “I don’t know Spanish.”

It was the second day of a summer camp created by the Los Angeles Theatre Academy to help children with Latino roots hold on to their Spanish.

But even in a city where everyone seems to speak un poquito de español, the goal is more easily set than accomplished. In a single Latino family with 10 grandchildren, Spanish proficiency may be all over the map. Some may be fluent. Others may know little more than adios and muchas gracias.

Some go to great lengths to keep the language alive — immersion schools, vacations in Latin America, Spanish-speaking nannies, quality time with abuelita.

Still, it’s a game of use it or lose it. And parents often find that the older children get, the more they gravitate toward monolingualism.

“It’s embarrassing,” said Rosa Figueroa, Elena’s mother, an attorney of Mexican descent who speaks fluent Spanish. “Here I am paying someone else to teach my daughter something that we should have obviously taught her. But what choice do we have now?”

The El Sereno resident has two daughters, Elena and 10-year-old Isabella. When the girls were toddlers and under their grandmother’s care, they were fluent in Spanish. But after preschool began, their ability began to fade.

Figueroa and her husband, who is of Colombian and Italian heritage, spoke only English at home. It’s what came naturally, she said.

“We always say, ‘OK, we’re going to do Spanish-only Sunday,’ ” Figueroa said. “But 30 minutes later, we’re back to English.”

She hoped enrolling her daughters in the camp would entice them to work on their Spanish — particularly Elena, who seems more resistant.

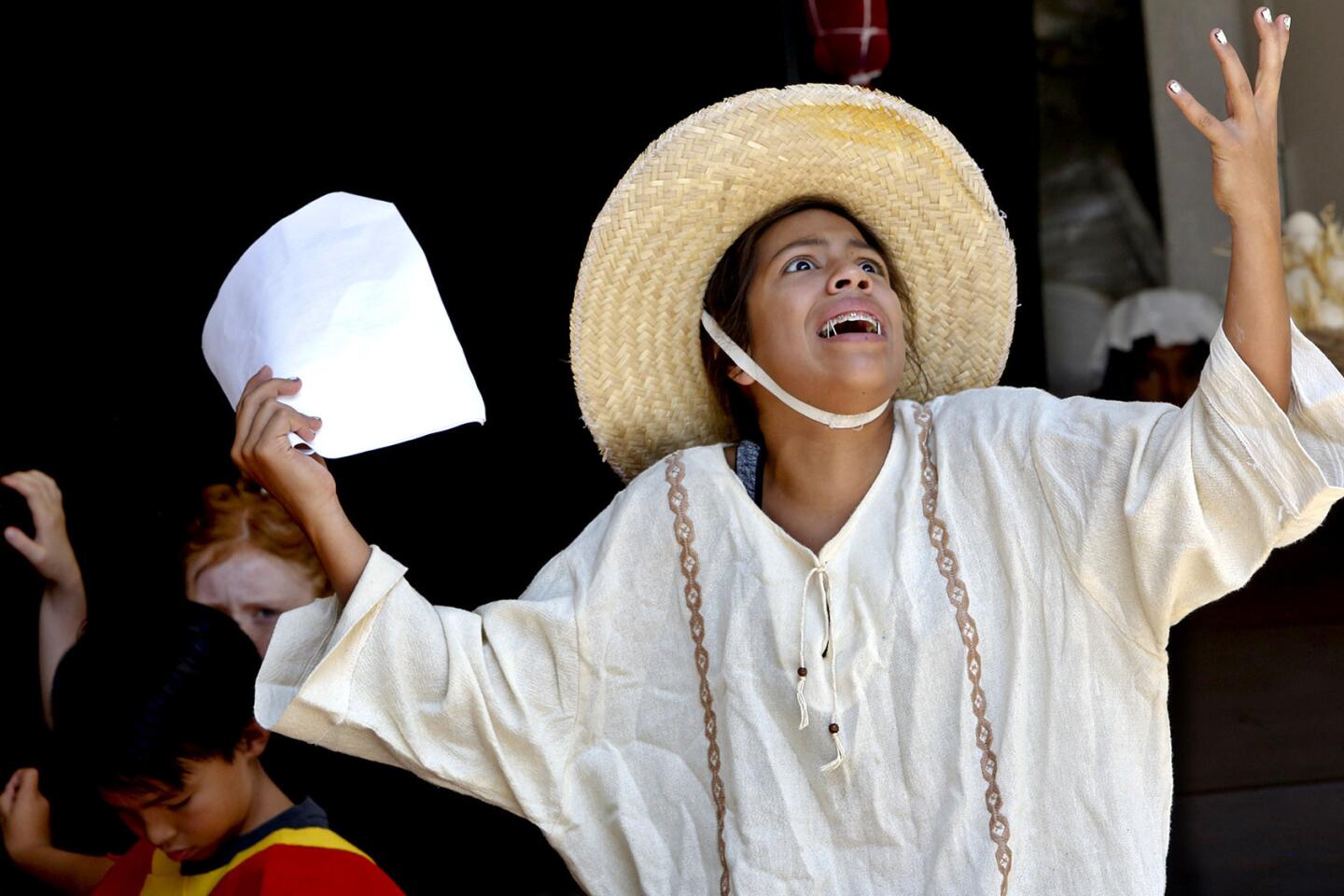

On a recent afternoon, the second-grader joined 13 other students on an outdoor stage, taking cues in Spanish from Alejandra Flores, the academy director.

“Eso!” Flores yelled in a strong stage director’s voice. “That’s it!”

“From the top now, voices clear and loud. Vamos!”

Flores, who has worked with children in theater for 20 years, began the academy five years ago out of a Los Angeles Parks and Recreation building at Elysian Park.

The program is modest, funded almost entirely by fees from parents. Children perform Spanish classics, scenes from plays and musicals, in a mix of Spanish and English.

Flores, who wears a fanny pack and carries a little brass bell that she rings to get her fidgety actors’ attention, uses each performance to teach vocabulary words, phrases, songs and, most all, confidence.

She occasionally offers Spanish classes on Saturdays, but some Latino parents, who drive in from as far as Valencia and Inglewood, wanted more: a Spanish-only camp.

This year, Flores told them: “OK, I’ll do it, but just be aware I’m going to be very strict with the kids.”

Most of the parents are professionals — sociologists, researchers, high school principals — eager to get any kind of help.

Their list of obstacles is long and varied: Some no longer live in Spanish-speaking neighborhoods. Others don’t speak Spanish or are married to a non-Spanish speaker. Some have few Latino friends or live far from Spanish-speaking relatives.

“It’s a constant struggle,” said Paola Suarez, who enrolled her son Camilo in the camp. “We’re always trying to find ways to keep him motivated so he doesn’t fall back.”

Suarez, from Colombia, has a husband who speaks Korean. Both would love for Camilo and his 3-year-old brother to grow up trilingual. Suarez speaks to the boys only in Spanish, and her husband speaks to them only in Korean. English TV and music are off-limits at home.

At 7 years old, Camilo fluidly switches from one language to the next. He can write and read relatively well in all three. What comes easiest?

“English,” Camilo said. “All my friends speak English and I know more words in English. Like the word ‘extract.’ I have no idea how to say ‘extract’ in Spanish. Do you?”

Like Suarez, many Latinos — non-Latinos too — are choosing to put up a fight for Spanish. A few generations ago, the opposite was true: English was king, and the desire was to blend in.

“But being bilingual is cool right now,” said Xavier Cagigas, director of the cultural neuropsychology initiative at UCLA. “It’s like a whole generation of people woke up and realized all the incentives.... It’s a passport to your culture, it makes you more marketable, it gives you a global perspective.”

According to census figures, the United States has the third-largest Spanish-speaking population in the world — outnumbering Spain and every Latin American country except Mexico and Colombia.

At 46, Luis Rodriguez of Elysian Park is well aware of the benefits of being bilingual.

His mother spoke Spanish to him while he was growing up — but he always answered her in English. Everyone at school communicated in English, so he saw no need to learn his mother’s language.

In his 20s, Rodriguez began a job at a therapy company. His bosses promoted him to manager, charged with overseeing the entireSpanish speaking market.

“They assumed I spoke Spanish, but I had no clue what I was doing,” Rodriguez said. “Each time I spoke with a client, I had to ask them to repeat things three, four times.”

Eventually, he said, he had no choice but to catch up.

When his daughter Jude was born, he was determined to teach her Spanish.

But his wife, a fourth-generation Mexican American, didn’t speak Spanish, either. And by the time he came home from work — long days spent translating and straining his mind to understand Spanish — all he wanted to speak was English.

Today Jude, a 14-year-old with an easy smile, is one of the oldest children in Flores’ camp.

As they rehearse a scene from “Don Quixote,” Jude holds tight to her libretto and does her best to bring Sancho Panza to life.

“Mire, señor!” she yells out. “Que aqui no hay encanto!”

Her accent is thick, and often she doesn’t know what she’s saying. So many words are impossible to pronounce: requesones, atreveria, ensuciar.

But she tries. Harder than most.

Jude said that a few years ago she began questioning her father about why he hadn’t taught her Spanish.

Rodriguez tried to find a program at her school, but L.A. Unified has only limited dual-language offerings. There were none in their neighborhood.

So Jude, on her own, found Flores and signed up for the academy.

“I’ve learned many things,” she said during a rehearsal break. “I can tell you my favorite color and what I ate for breakfast and I know how to say, ‘Help. I have a medical emergency!’

“But I want to know more,” Jude said. “A lot more.”

For information on upcoming summer shows, go to latheatreacademy.com.

Twitter: @LATbermudez

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.