The saga of Snoop Doggy Dogg

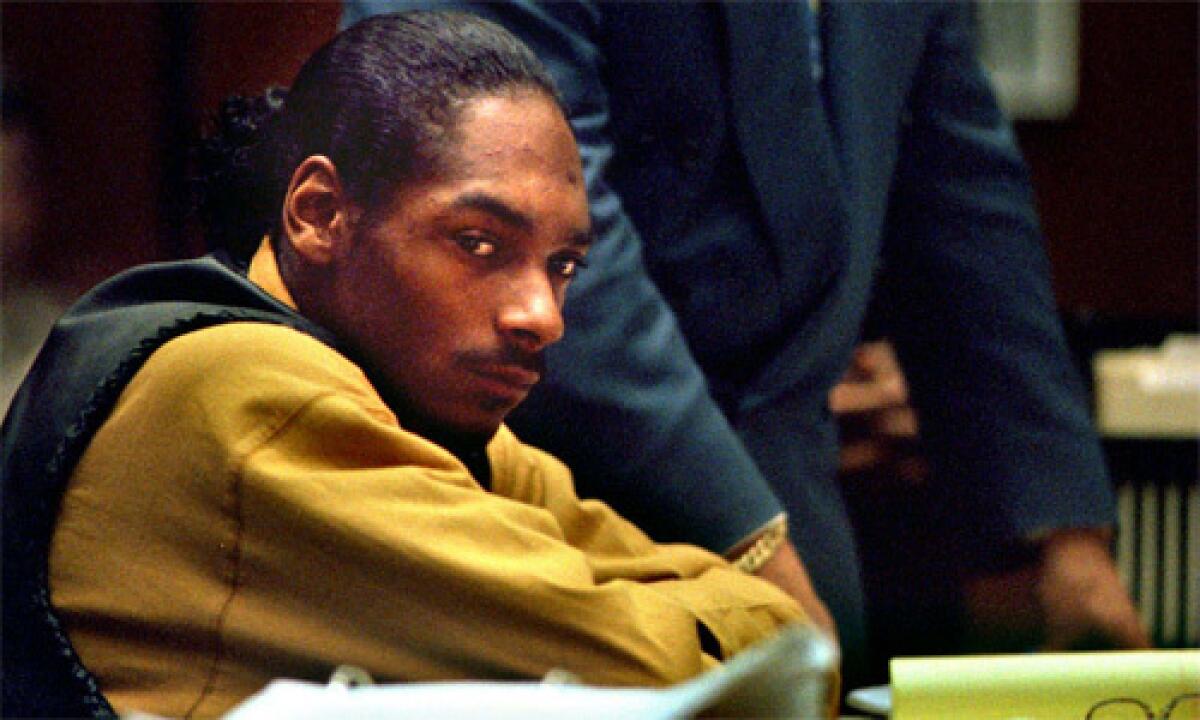

Sitting in a West Los Angeles recording studio, just around the corner from the police station where he was booked as an accomplice to murder, gangsta rapper Snoop Doggy Dogg has two important dates on his mind.

On Nov. 23, Interscope Records will release the 22-year-old Long Beach native’s debut solo album, “Doggy Style.”

Because of Snoop’s co-starring role in fellow rapper Dr. Dre’s recent smash album “The Chronic,” Snoop’s collection is expected to enter the national pop charts at No. 1--something no debut album has done since SoundScan began its computerized monitoring of record sales in 1991.

Then on Nov. 30, he’ll step into a West Los Angeles courtroom to face a murder charge stemming from an Aug. 25 shooting. Snoop, whose real name is Calvin Broadus, was arrested after driving the Jeep from which the fatal shots were fired by his bodyguard. If convicted, the 6-foot-4 rapper could spend the rest of his life in jail.

“There is nothing you can do to prepare yourself for what I’m going through,” says Snoop, twisting on his stool in front of the studio console. “But I believe everything happens for a reason. The ups. The downs. I just got to deal with it and keep on going. It’s all in God’s hands now.”

Snoop is part of the most dramatic confluence of violent art and violent reality the modern pop world has ever witnessed: gangsta rap.

The controversial musical genre--which started in Los Angeles during the ‘80s with stark, obscenity-laced albums by Ice-T and N.W.A.--has long been criticized for glorifying violence and degrading women. Gangsta rap became a front-page issue during last year’s presidential campaign after police groups threatened to boycott Ice-T’s Time-Warner-owned record company because of “cop killer” lyrics.

The debate escalated further when artists such as Snoop began running into trouble with the law. Only last Sunday, Tupac Amaru Shakur, who also records for Interscope, was arrested in Atlanta for allegedly shooting two off-duty police officers. (Though not part of the gangsta rap scene, another hard-core rapper, Public Enemy’s Flavor Flav, was also booked in New York the following day for allegedly trying to shoot another man in a dispute over a woman.)

Unlike the stark, confrontational tone of much gangsta rap, Snoop’s lyrics and funky, laid-back delivery are not concerned with racial politics but celebrate survival in the misogynistic gang-war era, delineating what it’s like to be an urban black male in the dangerous ‘90s.

“Anyone who knows anything about music in this industry has tremendous respect for Snoop as an artist,” says Russell Simmons, chief executive officer of New York-based Rush Communications. “He is the dopest new vocalist on the scene.”

Ken Barnes, senior vice president and editor of the trade weekly Radio & Records, thinks the rapper demonstrates a potential for huge crossover success.

“There is a definite place for Snoop’s music in the pop world,” Barnes says. “His work with Dr. Dre is extremely seductive and approachable. I can see him getting even bigger--as long as his image doesn’t scare the pop (radio) stations away.”

*

It’s 21 days past the deadline for the new album and Snoop is still not finished with the vocals for the last two tracks on the collection.

A half dozen musicians hover around him in the studio as Interscope Records president Jimmy Iovine anxiously questions producer Dr. Dre as to whether they will meet the latest deadline--the one that will allow the album to be released in two weeks. Dre reassures him the deadline will be met.

The pressure is on from retailers and the Warner Music Group, the multibillion-dollar distribution arm of Interscope’s parent company, but Snoop looks calm.

Dressed in a baggy purple sweat suit, the rapper jokes with his Long Beach buddies Nate Dogg and Warren G and launches into a dead-on Beavis and Butt-head impersonation, explaining, “I like things that make me laugh. I enjoy humor.”

The nickname Snoop , he says, was given to him by his mother, but the rest of his stage moniker was lifted from a cousin who used to call himself Tate Doggy Dog. “When I decided to call myself Snoop Doggy Dogg, he didn’t much like it, but I said to him, ‘Tate, I’m gonna take this name to the stars.’ ”

After boasting about his skills on the computer game Sega, he reminisces with his homeboys about the R&B group they formed “back in the days.”

Given the hard-core gangsta persona he perpetuates in photos and on record, the polite and gentle manner in which he speaks with his pals is not what you’d expect.

But Snoop is full of surprises.

For the most part, his musical heroes are not contemporary rap artists, but soul singers like Al Green, Curtis Mayfield and L. J. Reynolds of the Dramatics. He can recite the lyrics to classic love songs and speaks reverently about their influence on his vocal style.

“I’m just a student, man,” he says quietly, his brown eyes beaming with intensity. “It’s like I’m studying for an exam. My goal is to outdo everybody--to get the highest grade.”

Unlike other hard-core rappers, Snoop seems unafraid to show his soft side. He talks warmly about family and friends and waxes philosophical about faith and his desire to perfect his craft and improve his lot.

In fact, his favorite track on the new album is a gospel-tinged tribute to his mother titled “Gangsta Life.”

“It’s about how my mama raised me and my brothers on her own and how we got caught up on the streets,” he says of the song, which features the backing of a gospel chorus. “In the song I give my mama her respect and yet I try to show just what the wages are for kids not paying attention. I ain’t no gospel rap musician, man, but I got faith in what I believe in.”

So why did he pose for magazines earlier this year, boldly brandishing a pistol?

“Back then, I was new to the game, you understand,” he says of those stark, pistol-toting poses. “The photographers would tell me, ‘Hey, man, take a picture with a gun and you’ll look real hard.’ And that’s what I did. I sold myself to the T and now I’m in the house. But you don’t see me posin’ with no guns anymore, you know what I’m saying?”

Those who know him well say Snoop remains relatively untouched by the excitement surrounding his sudden rise to stardom. While his bank account gets fatter by the day, they say he still hangs out with the homeboys and frequently visits his old stamping grounds.

Success, however, is helping Snoop put his own turbulent past into perspective. Despite criticism from media watchdog groups and family organizations that he glorifies criminal behavior with his music, the rapper sees himself as a positive role model and hopes his fame will inspire gangbangers to put down their guns and pick up a mike.

“The media is quick to point their finger when trouble strikes, but nobody ever asks a successful rapper like me how he feels about what’s going on in the ‘hood,” Snoop says. “I guess they think I’m macho and I don’t care or something. But man, I’m someone who’s trying to turn his life around. And it gets emotional.

“A dozen people I know have been smoked for no reason at all. I wish the violence would stop. I mean, right now I got some little homeboys coming up who are happy to see me doing right, but it’s so dangerous out there they might not even live to see my album come out.”

*

Snoop is no stranger to gang violence.

Born and raised in a tough section of eastern Long Beach, he tells of being caught up early on in the cross-fire of turf fights between various factions of the notorious Crips gang.

The community he grew up in is a hodgepodge of window-barred wood-and-stucco bungalows police say is plagued by crack dealing, car-stealing and drive-by shootings.

“On a danger scale of 1 to 10, Long Beach rates about a 9,” suggests one Long Beach Police Gang Task Force agent. “The gang situation has been way out of control there for more than a decade.”

As a child, Snoop sold candy, delivered newspapers and bagged groceries to help his mother and two brothers make ends meet after his father moved to Detroit. He says he was a dedicated student and athlete who looked forward to attending weekly services at one of the neighborhood’s many storefront churches.

Despite his mother’s best efforts to keep him singing in the choir and playing football, Snoop says he fell in with the wrong crowd during his teens and started running the streets and hustling dope. However, he denies reports circulating in the media and among Long Beach police sources that he was ever a bona fide Crip.

“If you’re white and you grow up in a KKK neighborhood, people out there are going to label you a racist,” Snoop says. “The neighborhood I grew up in was full of Crips. That was just one of those labels I had to adjust to. It was a jacket that I had to wear for awhile. So I wore it and then I took it off.”

Barely one month after he graduated from Long Beach Polytechnic High School, the rapper was incarcerated on a drug charge, and he returned to jail several times on probation violations.

“I want to stress something to the little kids out there: There ain’t nothin’ cool about selling dope,” Snoop says. “I did it because I thought it was cool but I was wrong and I went to jail for it.

“But when I was rappin’ in the county jail, a lot of the older inmates told me, ‘Man, you’re too talented to be in here. You need to be outside, not wasting your life away with crime.’

“I don’t want anybody to get the wrong idea, though. Life in the ghetto ain’t easy like they want to make it seem. People take wrong turns for a reason. You wake up in the morning and there’s no work. Nobody has nothin’. That’s what makes them want to go take it from the next man. That’s what leads to all the trouble and commotion. Man, I mean it’s really tore up.”

After his release, Snoop says he quit dealing drugs and began to concentrate seriously on becoming a professional musician. By this time, he had already been rapping for seven years--ever since performing a song in front of his sixth-grade class called “Super Rhymes.”

His classmates’ positive response was so overwhelming Snoop began to devote long hours every night after school studying the chops of professional rappers and honing his craft with neighborhood friends.

He patterned his style after East Coast rappers, his biggest idol being Slick Rick (who also eventually got into trouble with the law over a shooting and is now in jail). By the time he was 15, Snoop had a reputation on the streets of Long Beach as one of the city’s hippest young rappers.

“When I rapped in the hallways at school I would draw such a big crowd that the principal would think there was a fight going on,” he remembers. “It made me begin to realize that I had a gift. I could tell that my raps interested people and that made me interested in myself.”

Before long, Snoop was writing and recording his own material. He soon signed a 90-day record contract with a talent agent from Carson, but backed out of the deal after being pressured to tone down his lyrics.

After working with several Long Beach rap partners, Snoop formed a rap and R&B group with Nate Dogg and Warren G called 213. The trio was so popular in Long Beach that they were able to sell more than 500 homemade tapes of Snoop’s material to rap fans out of the trunk of a car--one of which eventually found its way into the hands of Dr. Dre, the N.W.A. founder who was trying to launch a solo career.

“One day the phone rang and the voice on the other end says to me, ‘This is Dr. Dre,’ ” Snoop recalls. “Man, I couldn’t believe my ears. I said, ‘No way, who is this really?’ He says, ‘You want to make a record with me or not?’ I said, ‘Hell, yeah.’ ”

Less than a year later, Snoop’s voice was blasting out of boomboxes from Compton to Harlem as a featured vocalist on Dre’s first solo outing, the title soundtrack single from the feature film “Deep Cover,” which describes the murder of an undercover cop.

His deft phrasing and catchy melodic chants also played a prominent role in the success of Dr. Dre’s “The Chronic” album, which has sold 3 million copies since last December. He wrote most of the album’s lyrics, raps on the whole album and is featured soloist on four of the tracks. Even before Dre’s “Nuthin’ But a ‘G’ Thang”--which Snoop wrote in 1990 and raps on--cracked the Top 10 last spring, critics began hailing Snoop as the nation’s hottest hip-hop attraction.

“Snoop is the most unique rapper to emerge in years,” says James Bernard, senior editor of the New York-based Source, the nation’s leading rap journal. “Nobody out there matches his melodic flow. What you have here is an extremely talented guy who has clearly brought his own world view to the mike.”

The intense interest in Snoop not only demonstrates the commercial viability of graphic, hard-core rap, but also provides the clearest example of a talented young artist grappling to rise above the violent inner-city lifestyle depicted in his music.

“What I’m doing now is something I’ve always dreamed of accomplishing,” Snoop says. “You can’t pre-plan for overnight success. There are too many obstacles. People try to give you advice, but there ain’t nobody out there who can understand what’s goin’ on until they actually ride in the front seat.”

*

Snoop was sitting in the driver’s seat of his black, 1993 Jeep on Aug. 25 when, witnesses told police, an argument broke out between his pal Shawn Abrams and Philip Woldermariam in a park in the Palms area of West Los Angeles, leading to a shooting.

That argument, sources say, followed an earlier shouting match that afternoon in front of Snoop’s apartment during which Woldermariam allegedly brandished a weapon and threatened the rapper’s life.

According to police, Snoop, his bodyguard McKinley Lee and Abrams chased Woldermariam to Woodbine Park three blocks away where at 7:20 p.m. Lee shot Woldermariam.

Lee says he shot in self-defense after Woldermariam allegedly pointed a pistol at the vehicle.

Snoop’s attorney, David Kenner, says Woldermariam--on probation after serving a one-year jail term for negligently firing a firearm on public property--had previously assaulted Snoop with a gun, held it to his head at a gas station and threatened his life during the recent filming of a video.

Deputy Dist. Atty. Edward Nison of the Hardcore Gang Division says Kenner and the bodyguard’s explanation of the events has been disputed by several independent witnesses. Nison says a coroner’s report reveals that the victim was shot in the back and, according to witnesses, unarmed at the time of the shooting.

Kenner maintains that a medical report taken at the hospital determined that the bullet entered from the front of Woldermariam’s body to the back. The attorney also says he has an independent witness who saw the wounded Woldermariam get rid of his gun at the park.

Kenner negotiated an agreement with detectives at the Los Angeles Police Department’s Pacific Station that Snoop would surrender immediately after appearing as a presenter on the MTV Video Music Awards at the Universal Amphitheatre Sept. 2. He pleaded not guilty to the charges on Oct. 1 and has been free on $1-million bail. Preliminary hearings for the case, which is expected to go to trial early next year, begin on Nov. 30.

When the subject is raised in the studio, Snoop looks somber, but says his lawyer has told him not to comment on the case.

It’s only when the conversation shifts back to the music that he looks up and begins to come alive again.

“My music makes people happy, not violent,” he says, hunched over the console board. “I try to write songs that people will enjoy enough to reach into their pocket and spend their money on. I try to write classic songs that will last and reach all audiences: the gangstas, the gospels, the whites, the blacks, everybody. Me and Dre are doing something new. It’s art.”

*

Snoop’s been talking more than an hour now and people around the studio are getting anxious. They want him to get to work. If this deadline passes, the album might not be out in time to cash in on the lucrative holiday sales period.

But the rapper does not seem unduly concerned. He’s aware of the highly competitive nature of rap these days, but is also confident of his own abilities.

“In the rap world, you can be up for one high second and then down for the whole next year,” he says, tapping his fingers on the mixing board. “As quick as I came up that’s how quick they’re going to try to push me out of the game. So you want to try to keep your name proper and your game proper.

“(Rap fans) ain’t true to artists like fans are in country singing or rock. But I ain’t worried about it. My people expect professionalism at all times and that’s exactly what I give ‘em.”

The prediction for months in the record industry has been that Snoop’s long-delayed debut will burst onto the national pop charts at No. 1. The talk among industry insiders, in fact, is that the controversy surrounding the murder charge could even push album sales past the 400,000 mark during its first week in the stores. If true, that would put Snoop in the company of first-week sales splashes by such superstars as Michael Jackson and Metallica.

“What’s My Name?,” the first video from the album, shows the rapper transforming into a Doberman pinscher and being chased by “dogg” catchers, and is already playing on MTV. The song is also receiving extensive airplay at radio stations across the country.

Snoop climbs up on a platform above the mixing board and starts dancing to an undulating bassline that is pumping out of the speakers behind him. The heads of six musicians in the room bob in unison as a keyboardist in the corner starts practicing a synthesized flute solo and Dr. Dre turns knobs and tweaks faders back and forth on the console.

As talk in the room begins to center on a background harmony that Dre wants to add to the track, he and Snoop smile at each other and spontaneously burst out into an impromptu falsetto rendition of Al Green’s “I’m So Tired of Being Alone.”

Looking down at his watch, Snoop says it’s time for him to get back to work.

“Who knows what’s going to happen, man?” he says, shaking hands with a musician who enters the glass-encased studio booth. “All I know is this is my job and I plan to rock the stage the best I know for as long as possible. I can’t mess my dream up being nervous or scared. Things will work out the way they must. I ain’t stronger than God. I can’t fight God’s will. The way I see it, elevation is the key. No matter what, you got to continue to rise up. Because man, if you ain’t elevating, you’re setting yourself up to fall.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.