Anti-poverty zone leaves out L.A.’s poorest

In January, President Obama announced a block-by-block approach to relieving poverty in Los Angeles. Federal money, he said, would pour into a newly created Promise Zone.

The boundaries encompassed crowded immigrant communities around MacArthur Park and Koreatown, as well as upscale areas of Hollywood and Los Feliz. Left out was South L.A., where the poverty rate is higher. The exclusion stunned many South L.A. leaders.

The strategy, presidential aides said, was to concentrate resources in communities where nonprofits or public agencies had already received one of the Obama administration’s signature urban renewal grants.

INTERACTIVE: Promise Zone misses more poverty

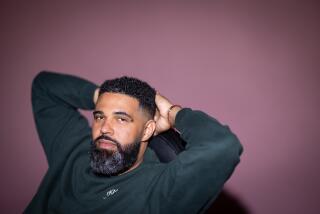

Only those previously funded organizations were eligible to seek Promise Zone aid. In Los Angeles, there was only one such group: a nonprofit led by Dixon Slingerland, a major campaign fundraiser for Obama and frequent White House visitor.

Under rules set by the White House and federal agencies, Mayor Eric Garcetti’s office, working with Slingerland’s Youth Policy Institute, was required to draw the zone’s boundaries around an area where the nonprofit already was focusing its federal grants — either Hollywood or the northeast San Fernando Valley.

The result was an anti-poverty zone that left out communities south of the 10 Freeway, including areas of chronic poverty that drew worldwide attention after the 1965 and 1992 riots. Neighborhoods around Watts have a poverty rate 21% higher than communities within the Promise Zone, according to a Times analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data. Neighborhoods east of USC have a poverty rate 39% higher.

U.S. Rep. Janice Hahn, part of a Democratic political dynasty that has represented South L.A. since the 1940s, pointedly skipped the White House ceremony at which Obama announced L.A.’s selection.

“It just seems like those that have keep getting,” Hahn said. “And those that never had don’t even have a chance.”

City Councilman Bernard C. Parks, who represents part of South L.A., said Slingerland’s political ties influenced the Promise Zone designation. “You know exactly why they came out first,” he said. “It was preordained.”

Slingerland disputed that. In an interview in his Hollywood office, he said he did not try to influence the Promise Zone eligibility criteria and that his campaign fundraising was irrelevant.

“It doesn’t help a darn bit,” he said.

Nationwide, 31 urban and rural areas applied for Promise Zones. White House spokesman Eric Schultz said merit and the program’s policy goals determined which applicants won.

“Some of the areas selected ... were backed by our political supporters, and some were backed by our most fervent political opponents,” he said of the five zones designated so far, including rural areas of Kentucky and Oklahoma. “But all of them have developed strong plans to create jobs, provide quality, affordable housing and expand educational opportunity.”

Promise Zones will receive priority in distribution of a range of federal grants, though the total amount L.A. will collect is uncertain.

The eligibility rules were intended to ensure that the program took advantage of progress already made in communities where public agencies and nonprofits have worked closely to combat poverty, the White House said. The idea was to measure the results and apply the lessons learned to impoverished communities nationwide.

Benjamin Torres, who runs the Community Development Technologies Center, a South L.A. nonprofit, said he understood the thinking behind the eligibility criteria. But he said they were “problematic” because they excluded too many impoverished communities.

For future Promise Zone applicants, the eligibility restrictions will be lifted.

Slingerland raised more than $743,000 for Obama in the last two presidential elections, according to internal campaign documents cited by the New York Times in a 2012 report on the president’s biggest fundraisers.

Since Obama took office, Slingerland has been to the White House 19 times, logs show. The visits included one to the residence for a reception, three to the West Wing and 10 to the Old Executive Office Building. He attended two receptions at Vice President Joe Biden’s home at the U.S. Naval Observatory.

Slingerland’s personal donations are also considerable. Since 2007, he’s given more than $179,000 to the campaigns of Obama, Garcetti, Gov. Jerry Brown, members of Congress, and state and local candidates, records show.

Slingerland grew up in Brooklyn, N.Y., and rural Ohio, the son of a Lutheran minister. He studied at Stanford University and then moved to Washington to work at the Youth Policy Institute, then an urban-poverty think tank founded by David L. Hackett, a close friend of Sen. Robert F. Kennedy.

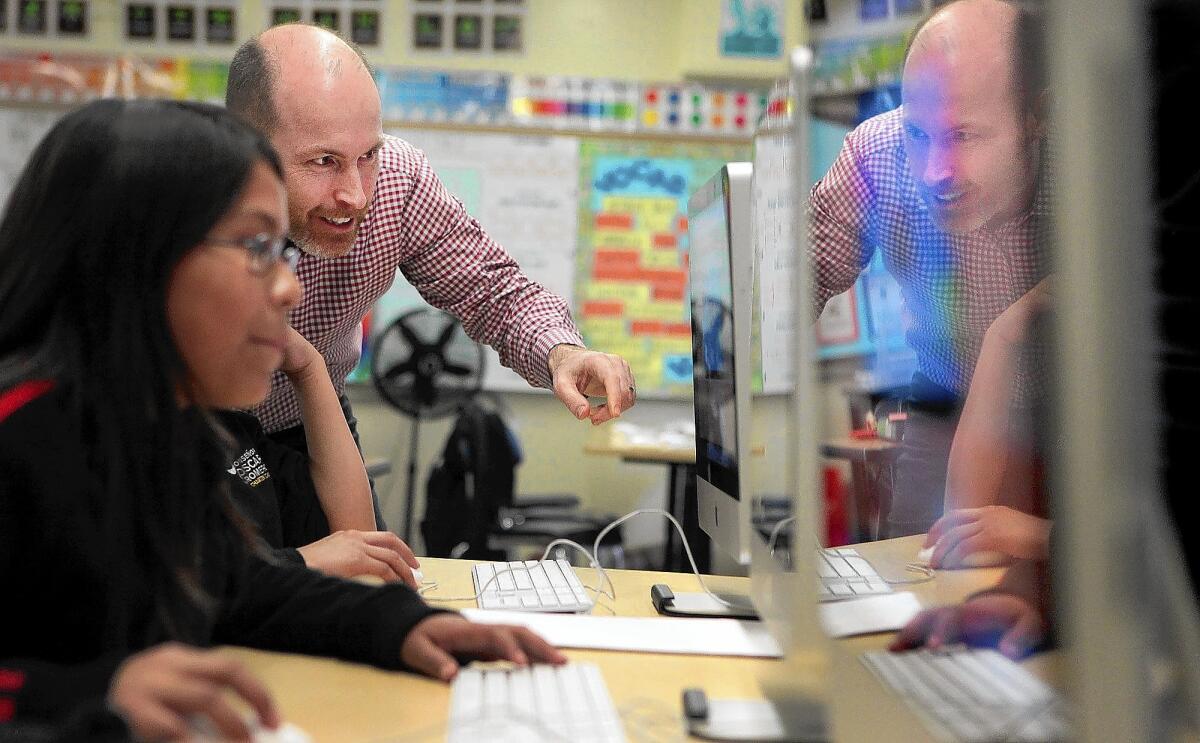

In 1996, Slingerland took over the institute, moved it to L.A. and shifted its focus to hands-on community work, starting with job training programs in Pacoima. In 2004, the group opened its first charter school there, followed a few years later by another in Pico-Union.

Over the last decade, the Youth Policy Institute has established itself in Hollywood, where in 2009 it opened a family services center in the same strip mall as then-Councilman Garcetti’s office.

Garcetti, who champions the sort of one-stop social services centers that the Youth Policy Institute runs, described Slingerland as “a very good connector of people.”

“I see him at a lot of things,” the mayor said. “He’s kind of omnipresent. It’s a little joke we make — that Dixon’s at everything.”

When Obama proposed the Promise Zones last year in his State of the Union address, he described the target as “inescapable pockets of poverty” and said the program would help “20 of the hardest-hit towns” in America get “back on their feet.”

There is plenty of need in the L.A. Promise Zone. Based on the formula used by the Obama administration, the poverty rate in the area is 35%. In the Watts area, it is 42%; east of USC, 48%.

“When I listen to the president talk about these initiatives, when you hear him talk about where he’s targeting, who he’s targeting, about changing the paradigm for these kids that have the odds stacked against them — you have to ask: Are these grants really fulfilling his goals for America?” Hahn said.

How the benefits — Garcetti is expecting tens of millions of dollars — will be spread across the zone hasn’t been determined. But some of the money could aid schools, community centers and businesses in parts of Hollywood, Koreatown and Los Feliz that have experienced strong economic growth in recent years.

A White House official, who declined to be quoted by name, defended the selection process. “Many of the most impoverished areas of the country are not ready for a coordinated federal program like this because they don’t have the basic plans in place to benefit,” the official said.

Federal agencies already spend billions of dollars a year on housing, transit, healthcare and other programs in the country’s poorest communities, the official added. “Poverty is poverty — and just because area A is more impoverished than area B doesn’t mean area B isn’t in great need,” the official said.

Garcetti said he was grateful for the federal aid and didn’t think Slingerland’s political clout gave him an edge. “I wish the rules would have allowed for more L.A. neighborhoods to be eligible,” the mayor said.

When an interagency group led by the White House decided on the eligibility rules in February 2013, Garcetti was a councilman running for mayor. Once he learned of the eligibility restrictions, Garcetti said, it was too late to get them changed.

As the formal Promise Zone applicant, the mayor’s office did have final say on the boundaries. Slingerland and others at the Youth Policy Institute worked on the map with a team led by Rick Jacobs, Garcetti’s deputy chief of staff. Limited to choosing between areas around Pacoima or Hollywood, which Garcetti had represented on the council for 12 years, the mayor picked Hollywood because it was better positioned to win the Promise Zone competition, a spokesman said.

Slingerland’s ties to the mayor are both political and governmental. Youth Policy Institute leaders co-hosted at least a dozen fundraisers for Garcetti’s mayoral campaign. Garcetti, who has spoken at the institute’s fundraising galas, voted as a councilman to fund its programs. Garcetti’s family foundation has also contributed to the institute.

Lingering bitterness over the Promise Zone selection has prompted Garcetti to publicize steps he’s taking to revitalize South Los Angeles. He recently convened a half-day gathering at City Hall to rally civic leaders behind those efforts.

Still, at the end of a Jefferson Park community meeting on his budget plans, Adela Barajas, founder of a South L.A. civil rights group, confronted the mayor as he walked toward his black sport utility vehicle.

“Promise Zone. South-Central. Why?” she asked as they walked.

“It didn’t qualify,” Garcetti said.

“Come on, now,” she said in disbelief.

“The White House said you had to win a previous grant,” Garcetti responded. “And South L.A. didn’t win one.”

Methodology used by The Times to compute poverty rates

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.