Miloš Forman, Oscar-winning Czech director of ‘One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,’ dies at 86

Miloš Forman came of age as a filmmaker under the watchful eyes of the Soviets in postwar Czechoslovakia. And though he blossomed in exile in 1970s America, his memory of totalitarianism would forever be his muse.

In every one of his films, from “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” “Ragtime” and “Amadeus” to “The People vs. Larry Flynt” and “Man on the Moon,” Forman celebrated real-life outsiders and eccentrics who challenged the establishment with heroic self-expression.

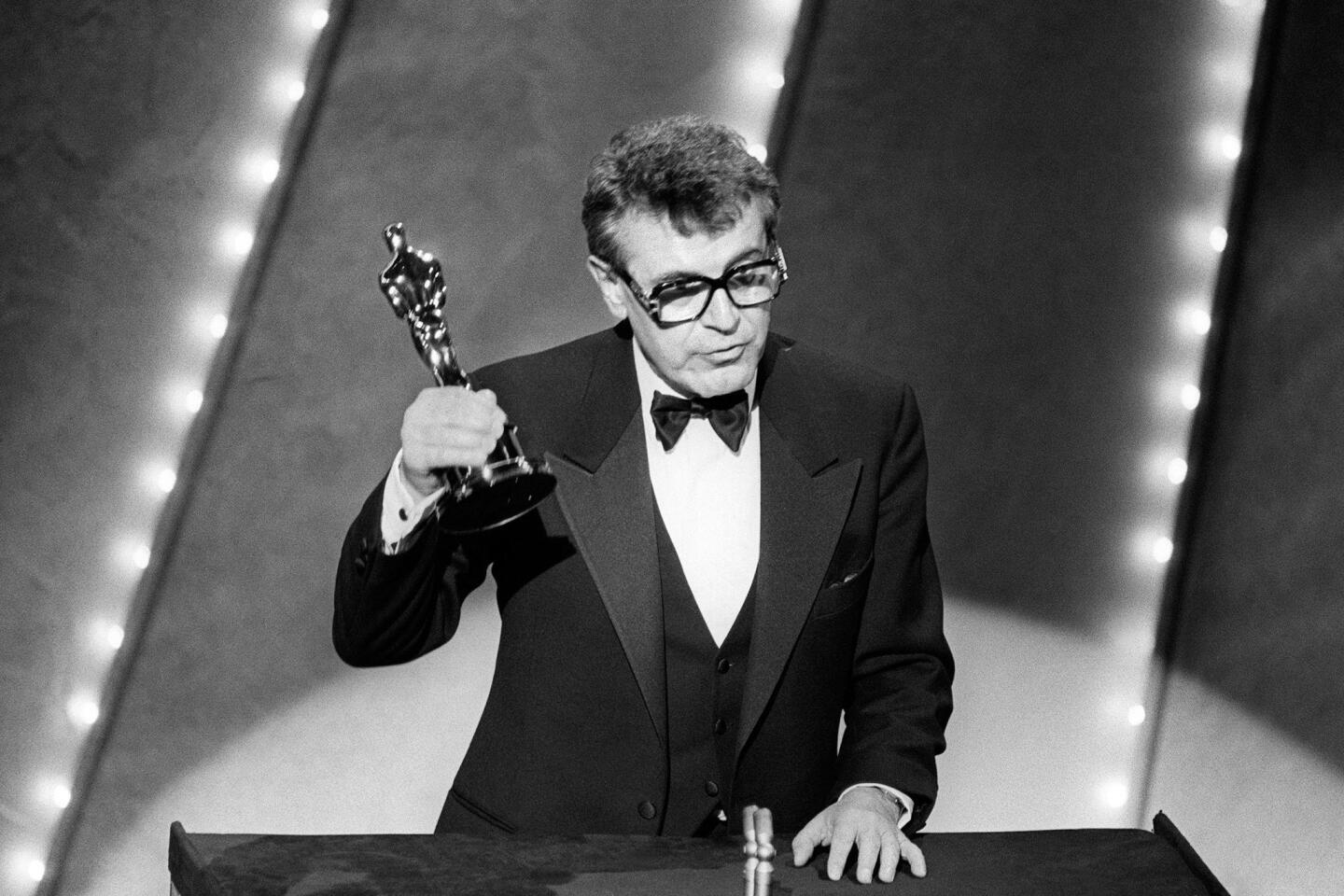

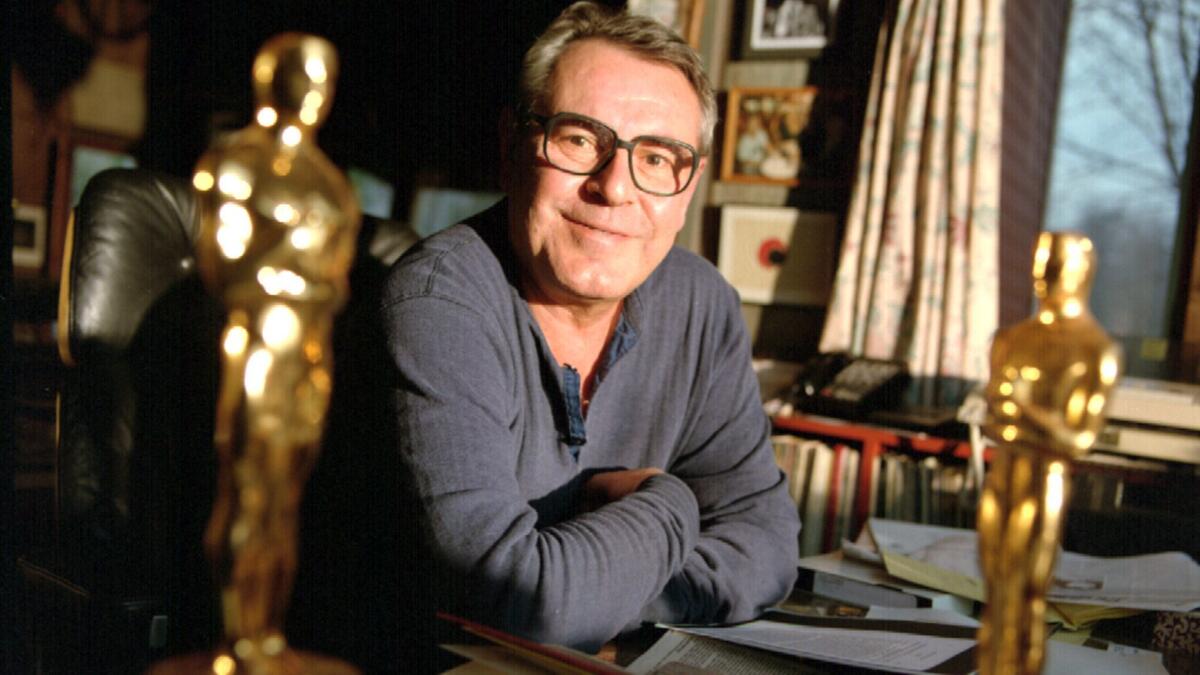

Forman died Friday at age 86 at Danbury Hospital, near his home in Warren, Conn., according to a statement released by his agent. A winner of two Academy Awards for directing “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” (1975) and “Amadeus” (1984), Forman was nominated again in 1997 for “The People vs. Larry Flynt.” His earlier films “The Fireman’s Ball” and “Loves of a Blonde” were nominated for best foreign language film.

Born Feb. 18, 1932, outside Prague, Forman was the youngest of three brothers. His father, a Jewish army reservist from World War I and university teacher, was arrested for disseminating banned books to his students. His Protestant mother was arrested after shopping at a local grocery where anti-Nazi propaganda was found. Both died in concentration camps, making Forman an orphan at age 10.

After World War II, as Czechoslovakia fell under Soviet control, Forman drifted from the homes of relatives to boarding school and then to the Prague Film Academy.

There, he helped establish the Czech New Wave, a group of filmmakers chronicling the grim realities of life behind the Iron Curtain. They favored documentary techniques, using long takes, improvised scenes and amateur actors.

“When we started to make our films they were really Czech films about Czech society and Czech little people — and who cares about Czech little people?” Forman told The Times in 2004. “So it was satisfying to have people in other countries respond.”

He earned international acclaim on the festival circuit with his feature debut in 1964 of “Black Peter.” Oscar nominations followed for his 1965 film “Loves of a Blonde” and 1967’s “The Firemen’s Ball.”

After that success, Forman was allowed by the Czech government to make a film in the U.S. But while he was in Paris negotiating the project, Soviet tanks rolled onto the streets of Prague, halting a dissident uprising. Rather than return home, Forman went to New York to live in exile.

He made his American debut in 1970 with “Taking Off,” a dark comedy about a teenage girl who runs away to be a hippie. But the film was a flop, Forman thought, because his storytelling didn’t translate and he couldn’t write in fluent English.

After years spent searching for inspiration, he was hired to direct the adaptation of Ken Kesey’s 1960 novel “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.”

It was a tricky shoot in an Oregon psychiatric hospital with real patients as extras. Some of the cast actually slept on the ward. Much of the dialogue was improvised. The cinematographer was fired more than halfway through and Jack Nicholson stopped speaking to Forman.

But when it was released, the movie was universally acclaimed, becoming only the second in history to earn an Oscar in every major category.

Though Forman had no experience in musicals and was pro-Vietnam War, he was eager to adapt the Broadway musical “Hair.” The hippie movement’s idealized notion of freedom fascinated him. His 1978 film adaptation earned critical acclaim and nominations for a César award and two Golden Globes.

Around that time, Forman settled into American life, becoming a naturalized citizen and buying an old dairy farm outside Danbury. He continued through the 1980s to make a film every few years, toiling for months on scripts, never taking a writing credit.

For his adaptation of E.L. Doctorow’s novel “Ragtime” in 1981, Forman brought James Cagney out of retirement. The film, which tells the story of a black piano player seeking justice against a white fireman who humiliates him, was nominated for eight Oscars and a Grammy.

Next, Forman returned to Czechoslovakia for the first time in more than a decade to shoot “Amadeus,” even though the production would be under the control of Czech State Security. When his crew pranked him by playing the “Star Spangled Banner” during playback, Forman panicked that they’d all end up in jail.

In the end, though, the film was one of his best, earning eight Oscars in 1984, including best director.

Forman took a long hiatus following the failure of “Valmont,” his 1988 adaptation of a book he loved in college, “Les Liaisons Dangereuses.” He resurfaced in 1996 with “The People vs. Larry Flynt.”

That film earned two Oscar nominations, one for Forman’s directing and another for star Woody Harrelson. But the Oscar campaign was hurt by Gloria Steinem’s criticism, claiming Forman glorified Flynt’s misogyny. Forman naturally argued in favor of freedom of speech.

“We have to fight for 100 percent freedom,” he told The Times in 1997. “Otherwise, we can lose it altogether.”

While shooting “Man in the Moon,” a quirky 1999 profile of the late provocateur Andy Kaufman, Forman endured the over-the-top Method acting antics of Jim Carrey. Carrey-as-Andy pummeled the director with obscenities and threw tantrums on set until Forman begged to let him get on with the movie.

Forman’s pace slowed after that. He went on in 2007 to direct the historical drama “Goya’s Ghosts” which was poorly received. That same year, he directed his first opera at the Czech National Theater in Prague.

Forman’s last film as a director was “A Walk Worthwhile,” a 2009 musical comedy released only in the Czech Republic. But he continued to generate ideas and serve as professor emeritus at the Columbia University film school.

In 2013, he received a Directors Guild of America Lifetime Achievement Award.

Forman is survived by his wife, Martina Forman; and children Petr Forman, Matěj Forman, Andrew Forman and James Forman.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.