From the archives: Federal inquiry finds rail oversight woefully inadequate

Reporting from Los Angeles and Washington — Widespread problems with enforcement of the nation’s railroad safety rules and sharp differences over what can be done to prevent future accidents have been exposed by the investigation of last year’s deadly Metrolink crash in Chatsworth.

A long-embraced pillar of train safety -- “efficiency” field testing -- came under fire Wednesday in Washington, D.C., from the chairwoman of the National Transportation Safety Board panel probing the crash that killed 25 and injured 135.

More effective policing of engineers and conductors is needed because train crews can spot supervisors approaching to do safety inspections, NTSB member Kathryn O’Leary Higgins told reporters.

“It’s a handful of people who all know each other. At least by evidence in this accident, I don’t think it’s effective,” she said of the field tests.

At least four serious breaches of safety regulations emerged in the examination of the Sept. 12 head-on collision between a commuter train and a Union Pacific freight train: on-duty cellphone use, an apparent failure to confirm signal colors, unauthorized ride-alongs in locomotive cabs and marijuana use by a freight train crew member.

Railroad officials conceded during two days of intense questioning that it is very difficult to catch violations such as cellphone use, which is suspected of contributing to the Chatsworth crash.

“I think it’s very widespread,” Higgins said after the hearing concluded. “I was not impressed with the answers, ‘We don’t know how to enforce it.’ ”

Enforcement gap

She took special aim at Metrolink. “I’m really disturbed by the fact that Metrolink has all these rules, but they weren’t really enforcing them,” Higgins said.

Metrolink has pointed to its efforts to increase field testing in recent months as a major reform. But the commuter rail agency still relies largely on the private contractor that provides its train crews, Connex Railroad, to oversee safety enforcement. Connex officials say the company has a strong safety record. It conducts 1,000 safety-related tests per month on Metrolink engineers and conductors and has convened an investigatory panel of experts, led by a former Amtrak chairman, to review its operating policies and practices.

Controlling ubiquitous cellphones has bedeviled regulators. At least eight serious U.S. passenger and freight train accidents have been tied to cellphone use since 2000. In one, the crews of both trains were using cellphones before the accident.

On the Metrolink and Union Pacific systems alone, hundreds of recent cellphone violations evidently have occurred, according to records and testimony from the NTSB inquiry.

Metrolink engineer Robert M. Sanchez, who investigators say was text-messaging about the time he sailed through a red light and slammed into the freight train, sent and received approximately 350 messages while scheduled to operate locomotives in the days before the crash. The conductor on the Union Pacific train sent and received 41 text messages while on duty the day of the crash, including 35 while his train was underway. And Union Pacific inspectors observed 643 cellphone violations on that system just in 2008, a company official said.

State and federal regulators responsible for independent oversight of railroads are woefully understaffed for the enforcement task, officials said. “Clearly we don’t have enough people to go around and inspect everything,” said Richard Clark, head of train safety programs for the California Public Utilities Commission.

Reform efforts

Railroad representatives Wednesday defended the industry’s safety record, saying accidents have been declining for the last decade because of improved training, better inspections and new technology to prevent collisions and detect defects in track and rolling stock.

Statistics from the Federal Railroad Administration show that train accidents have dropped from 2,768 in 1999 to 2,375 in 2008, a decline of 14.2%. However, the number of people injured in train accidents has more than doubled.

As a result of the Chatsworth crash, the worst in modern state history, Congress ordered trains to be controlled by computerized crash-avoidance technology within six years. The system would take over when engineers exceed speed limits or are in danger of running red lights.

In the burst of reform pledges following the Chatsworth crash, freight rails joined with Metrolink in promising to launch the new satellite-linked safety system in the Los Angeles Basin in just four years.

But a Union Pacific official testified that the task of equipping its entire U.S. fleet is enormous and the company is struggling to meet the federal 2015 deadline. “Right now, I would say that’s not likely,” said Jeff Young, assistant vice president for systems development. A showdown is looming over what to do in the interim.

Metrolink officials say they will be the first railroad in the nation to install live video cameras focused on train operators. “We believe the installation of cameras in the control cabs of our trains will provide a significant deterrent to the type of activity revealed during the NTSB hearing,” said Metrolink board President Keith Millhouse. The first cameras will be in place this summer, he said.

Metrolink board member Richard Katz said the NTSB hearings showed the shortcomings of relying on traditional field testing.

Video cameras are essential “because no matter what testing you do, you still have engineers and conductors alone in cars for long periods of time.”

But large and powerful unions representing the nation’s engineers and conductors on Wednesday insisted that placing two crew members in all train cabs is the solution.

“We certainly don’t support the requirement or the installation of any recording device” inside train cabs because of privacy concerns, said William Walpert, national secretary treasurer of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers and Trainmen.

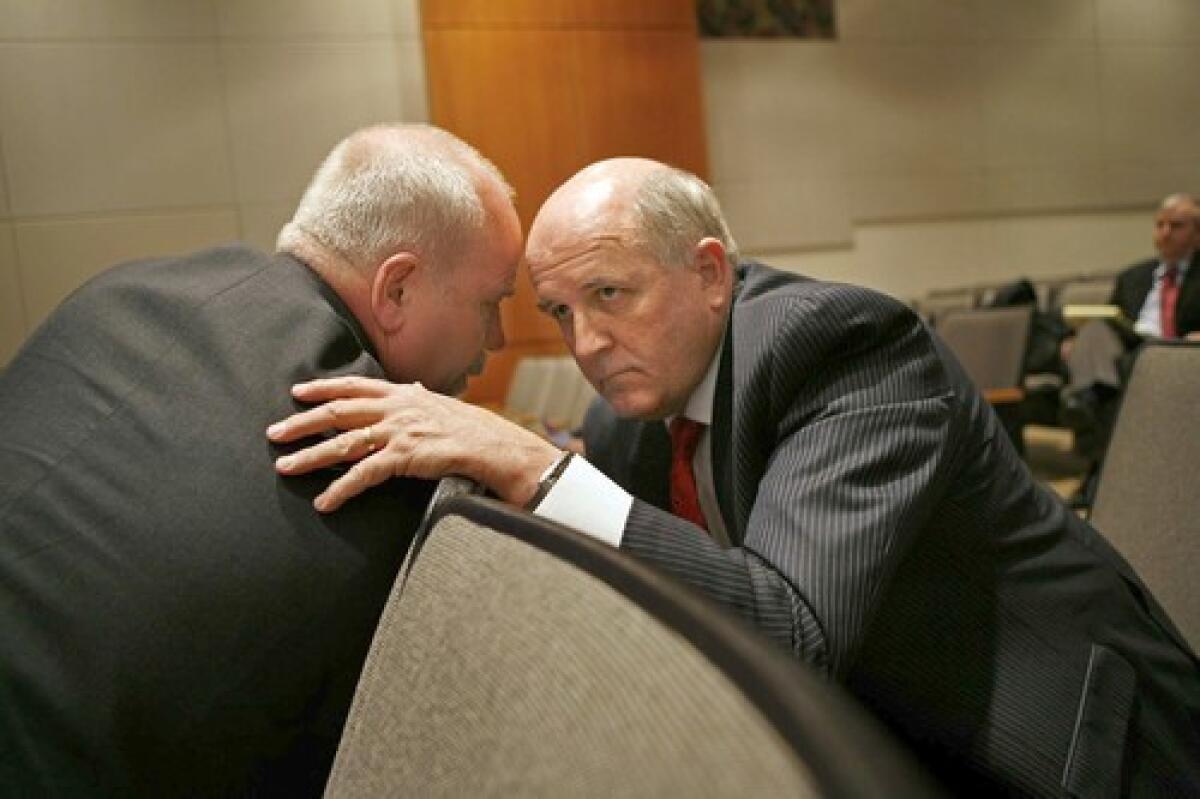

Jim Hall, NTSB chairman from 1994 to 2001, monitored the Metrolink crash hearing and came away distressed.

“It may be too early to draw conclusions, but it appears that the officials who testified were trying to describe a safety system that existed only on paper,” Hall said. “There weren’t really procedures in place to develop a safety culture with the operators and the individuals in the front office. They were just hiding behind the paper.”

Times staff writer Rich Connell contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.