Column: How ordinary folks waged battle against money and power at Newport Banning Ranch

The odds were not on the side of citizens who wanted to save 401 acres of coastal Orange County land from being turned into a small city with more than a thousand homes, a resort, commercial properties and open space.

They were up against Big Oil and real estate companies with clout, pockets as deep as oil wells, and teams of high-priced lawyers and lobbyists.

They were up against a Newport Beach City Council and Chamber of Commerce that cheered on the oil company and its real estate partners.

They were up against a Coastal Commission that had fired the director who said a big development would deliver a crushing blow to plant and wildlife on a critical, fragile environment.

And as they tried to recruit fellow citizens to their cause, they were up against a lack of awareness.

But last week, David smacked Goliath in the chops.

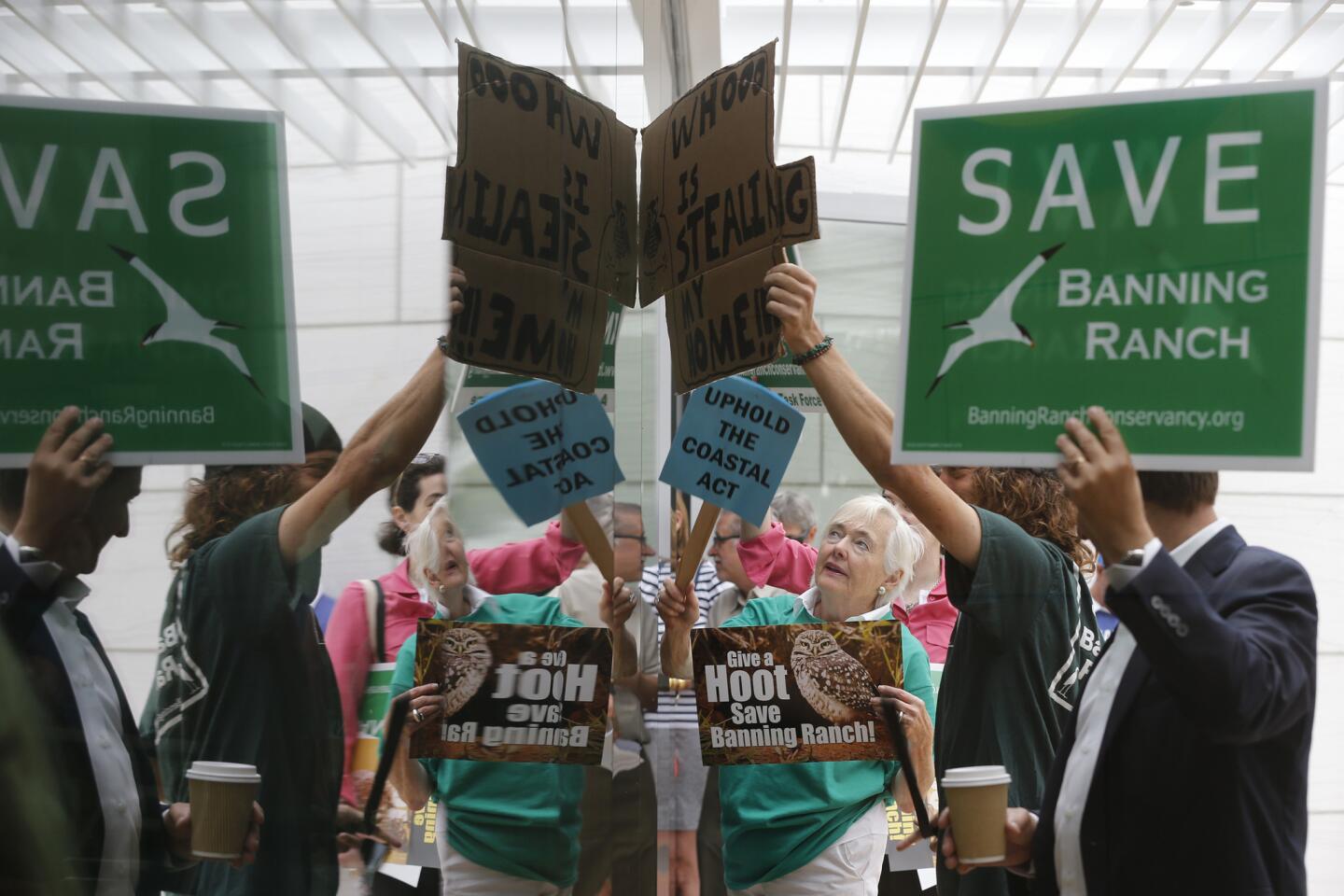

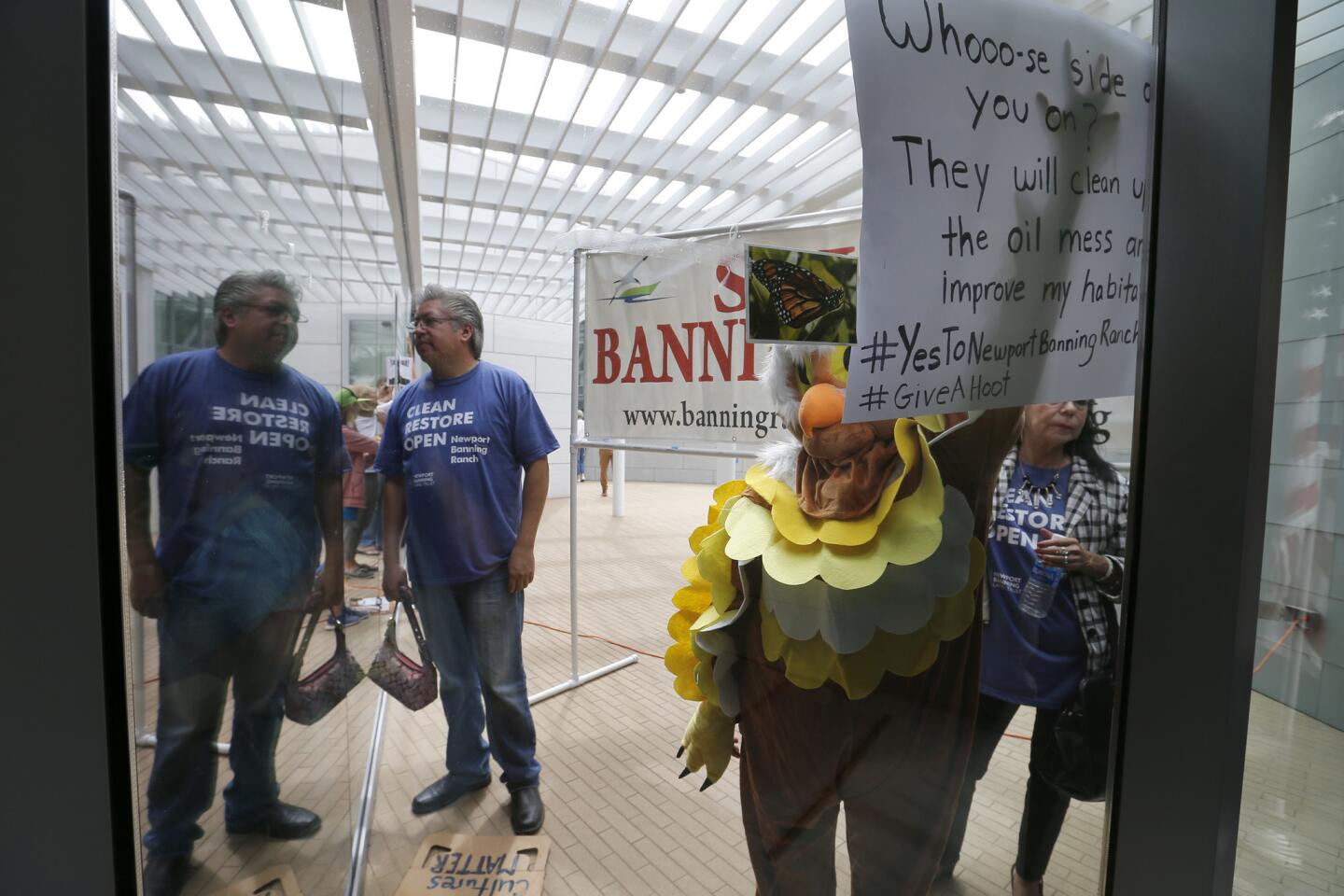

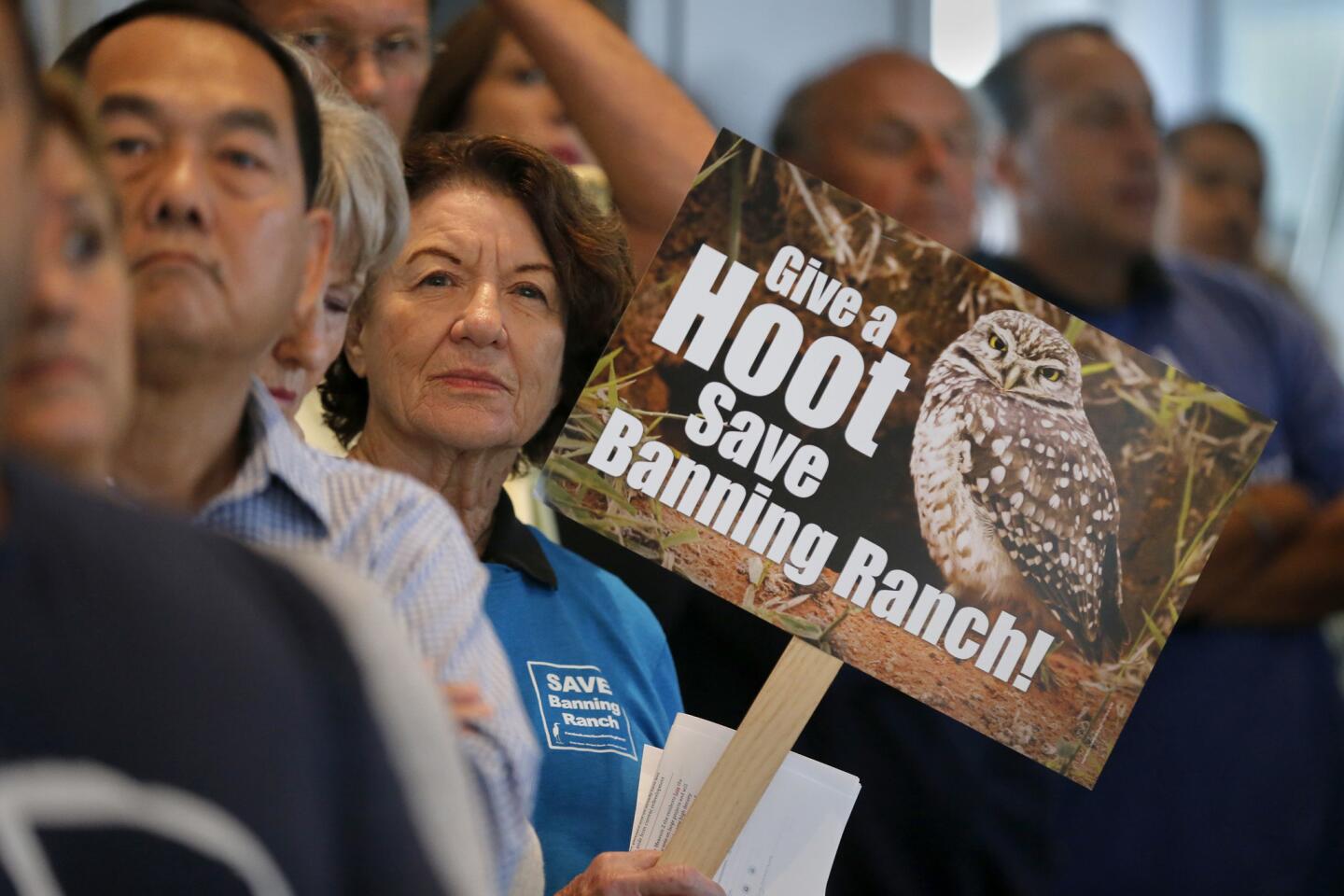

The citizens brigade broke into applause late Wednesday evening when coastal commissioners rejected the roughly $1-billion Newport Banning Ranch project on a 9-1 vote that left several members of the development team stricken.

“I don’t generally show a lot of emotion,” said Steve Ray, executive director of the Banning Ranch Conservancy, which fought the project for years. “But I kind of stood up and let out a big ‘whoop!’ and turned around and fist-pumped the crowd, and the cheering just got louder.”

This is the last large, undeveloped, privately owned space on the Southern California coast, and Ray and his allies have a radical vision that it ought to remain that way. Instead of million-dollar homes and a luxury resort, they want the oil-damaged brownfield overlooking the Pacific Ocean restored, with plant and animal life protected.

Ray and his cohorts expect more challenges ahead. The developers might contest the rejection in court, or try to push through a revised development on the partially-functioning, partially-degraded oil field they own. Despite the lopsided vote against the project, some coastal commissioners indicated they think there should be some type of development there. So what the opponents celebrated Wednesday was a significant victory in an ongoing war.

The opposition had to have figured into the decision, though we don’t know how big a factor it was. Still, looking back to the beginning of the citizen uprising, there are lessons in how to take on powerful forces.

It all began with Terry Welsh, a young physician who played a minor role in helping to save the nearby Bolsa Chica wetlands from a massive development pitch. Among Welsh’s mentors was fellow physician and revered environmentalist Jan Vandersloot, who was soft-spoken, hard-working and passionate about conservation.

In 1999, Welsh learned of a plan to develop Newport Banning Ranch, and he set up a monthly task force with the help of a local Sierra Club chapter.

Things did not begin particularly well.

“There were at least two times where it was just me and one other person in the room,” said Welsh.

But he did what they’d done in Bolsa Chica. He kept at it, modeling the late Vandersloot’s calm, steadfast resolve.

“If I could tell anybody anything about trying to preserve open space, you have to have monthly meetings and stick with it, and you’ll create a movement,” said Welsh. “It’ll start taking on a life of it’s own. Critical mass.”

Soon the gatherings were held at local restaurants, including the Spaghetti Bender. And then the Mesa Verde United Methodist Church joined the cause and offered space for the monthly meetings.

Ray, who had also volunteered at Bolsa Chica, was winding down his career as a movie producer and hooked up with Welsh in 2008, when they designed a strategy for the nonprofit Banning Ranch Conservancy. Ray, who’d been a Marine Corps special operations officer, helped draw up a plan whose objective was not just to stop development on Banning Ranch, but to buy, restore and conserve the property. While Banning Ranch is private property, they argue the state’s coastal act prohibits development there, a point the landowners strongly dispute.

One lesson Ray had taken from the Bolsa Chica victory was that “you gotta do the science,” so you have some credibility when you appear before regulators or challenge developers’ claims about whether the property is an environmentally sensitive habitat.

“If you talk to Terry about the science of vernal pools or burrowing owls,” said Ray, “you’ll think you’re talking to a guy with a PhD.”

Welsh wasn’t the only one who educated himself well enough to speak with authority about what — despite the environmental damage caused by the owners — has been called an invaluable mesa and wetlands ecosystem that is one of the last of its kind in California.

Software company owner Kevin Nelson, who’d grown up riding his bike past the property on his way to the beach, studied and challenged developer claims about the ecology, and whether the land owners were destroying habitat by mowing vegetation down to the nub.

When the amateur scientists needed backup, they went to pros including Robb Hamilton and Pete Bloom, who offered expertise on the threatened owl habitat, among other things.

Cindy Black, a retired federal agricultural technician, pulled records on the exact location of active and abandoned oil wells and their proximity to wildlife. She bought a used camera on Craigslist for $125 and began photographing owls and their burrows.

Suzanne Forster, Wendy Leece and Dorothy Kraus began what they called the Quality of Life Coalition and went door-to-door to warn of the noise, toxic dust and gridlock the project would cause.

The Banning Ranch Conservancy’s supporters haven’t always agreed on strategies, Welsh said, and some have formed their own groups. But that’s often been complementary, he added.

Last fall, as developers moved forward with their plans, Costa Mesa resident Olga Zapata-Reynolds, an elementary school teacher, started Saving Banning Ranch Together and began knocking on doors to make her pitch. She challenged the developers’ claims that they couldn’t afford to provide public access, restore habitat and clean up the mess they’d caused on the oil field unless a huge money-making development was approved.

Zapata-Reynolds’ field marshals included Nova Wheeler, Bill McCarty and Isabelle Phillips. Together they produced educational videos, joined a boat parade to market their mission, set up a phone tree and spent long hours handing out leaflets on the Pacific Coast Highway.

Olga’s daughter Arlis Reynolds, a mechanical engineer, helped launch a social media campaign to pull young people into the brigade, and the new recruits spread the word that the project would bring more million-dollar homes to an already-cluttered and congested coast with limited open space and little affordable housing. The mother-daughter team also reached out to Angela Mooney D’Arcy of the Sacred Places Institute to tell the story of Native American history on Banning Ranch.

“I can honestly say we talked to thousands of people,” said Olga, who now counts surfers and young Greenpeace members such as Matthew Forth and Linda Rodriguez among her friends.

The future of Banning Ranch remains in doubt, as the developers decide what to do next.

The tireless citizens’ brigade is prepared to march again, if necessary, in the spirit of like-minded activists who rose up statewide four decades ago in support of the proposition that protects the entire coast of California.

But on Wednesday night, Terry Welsh, Steve Ray, Olga Zapata-Reynolds and hundreds of others stood and cheered as the vote was counted and the little guys won.

Get more of Steve Lopez’s work and follow him on Twitter @LATstevelopez

ALSO

Is the Banning Ranch proposal really dead? A look at where the O.C. coastal project goes from here

Lopez: A good day for the Coastal Commission, and conservation, in Newport Beach

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.