30 jailers punished for inmate beatings, report says

In the last two years, Los Angeles County sheriff’s officials have disciplined more than 30 jail employees for beating inmates or covering up the abuse, according to a report from the agency’s watchdog obtained by The Times.

Other deputies “get away” with unnecessary force against inmates because “they craft a story of justification … which may be impossible to disprove,” according to the report by the Office of Independent Review, which monitors discipline in the Sheriff’s Department.

The report comes in response to growing allegations of inmate abuse inside the nation’s largest jail system and has been released as the FBI investigates several cases of potentially criminal misconduct by deputies.

Full coverage: Jails under scrutiny

The report documents a dozen cases in which deputies were either fired or suspended in connection with inmate beatings. But those who were punished may be only a fraction of those who actually used excessive force. Investigations into excessive force, especially those that involve relatively minor injuries to an inmate, can be “lackluster, sometimes slanted and insufficiently thorough,” the report said.

The report by Michael Gennaco, who heads the Office of Independent Review, is expected to be made public Thursday. But even as the watchdog circulated his findings, department officials revealed Wednesday that several more deputies not mentioned in Gennaco’s report had just been disciplined in connection with the beating of an inmate.

In that case, an inmate who was concealing a makeshift knife in his rectum refused to be X-rayed. A sergeant instructed the deputies to handcuff the man to a bench while the sergeant went to consult with a supervisor. The deputies instead took him to a clinic inside Men’s Central Jail.

Gennaco, in an interview with The Times, said the deputies told the inmate that they had plans to put a bucket under him and “wait for nature to take its course.” The inmate allegedly took a swing at the deputies. After a short struggle, the deputies took the inmate to the ground, where he was punched, kicked, pepper-sprayed and kneed.

Footage captured by a camera attached to a deputy’s stun gun showed that the inmate was on his stomach, “with no evidence of resistance or movement, but the Taser is applied anyway,” Gennaco said. The stun gun was used a second time, and the footage again showed no resistance.

“The deputies wrote in their report that the reason the Taser was used is because the inmate was trying to crawl away,” Gennaco said. The footage disputed that, he said. One deputy was fired and three were suspended. The sheriff’s internal investigation into the 2010 incident will be forwarded to prosecutors for possible criminal charges.

Gennaco’s report to county officials described similar accounts of abuse. It catalogs a variety of factors that contribute to deputies using excessive force. Many of the 3,500 deputies working in custody facilities are newly hired and face the prospect of violence from inmates who have long criminal histories. Deputies are expected to use force to protect their colleagues and vulnerable inmates.

However, while most deputies complete their jail tours without engaging in misconduct, the environment “may tempt an ungrounded deputy to inflict unnecessary harassment or violence on an inmate who is not a threat but is simply giving him a difficult time,” the report said.

Attempts to prove misconduct are often thwarted by deputies and inmates who have incentives to lie and a lack of physical evidence to support conflicting accounts of what happened, underscoring the need for more surveillance cameras in the jails, the report said.

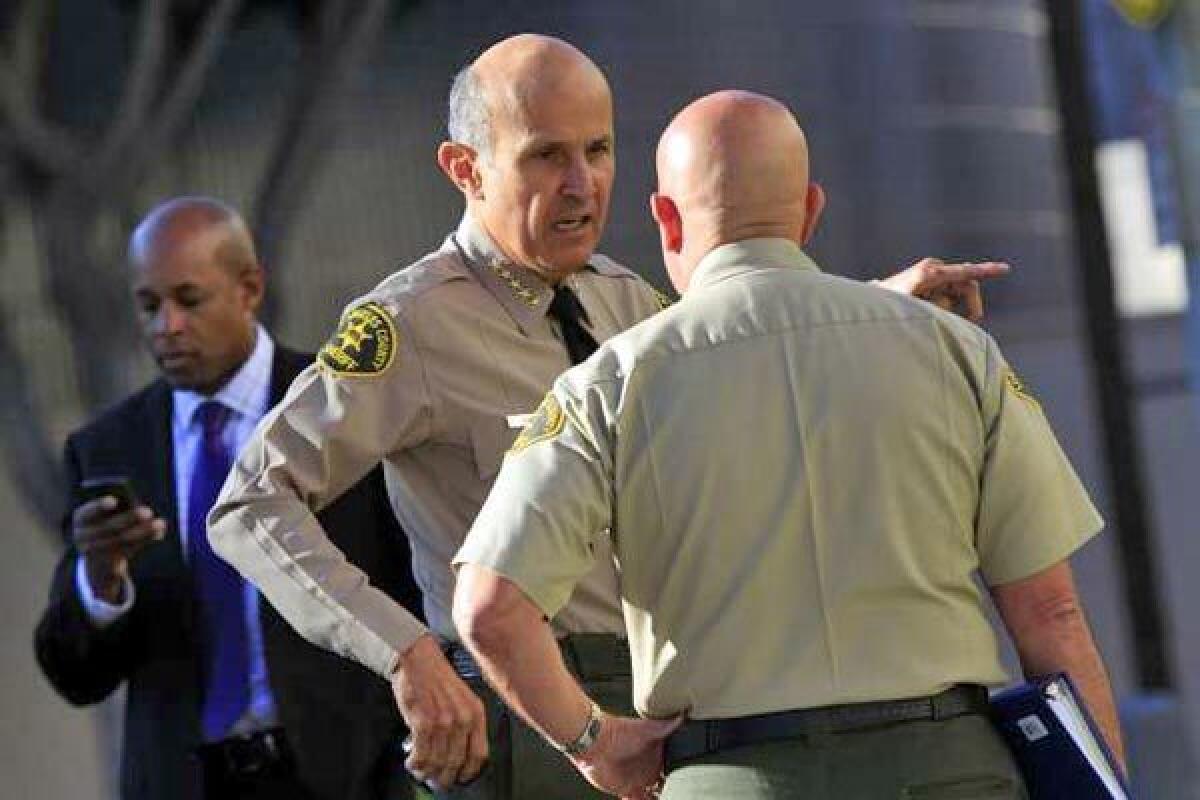

In some of the disciplinary cases in which video footage was available, the cameras provided evidence of excessive force that would not otherwise have been provable. Sheriff Lee Baca told The Times that he planned to install 69 cameras inside the Men’s Central Jail by the end of the year. Gennaco wrote that he was “heartened by the apparent activation of a too-long delayed plan.”

The report is at times critical of the department’s handling of abuse allegations and comes days after Gennaco drew fire from county Supervisors Zev Yaroslavsky and Gloria Molina, who questioned his independence.

The report said department investigators who examined minor force incidents sometimes failed to interview all potential witnesses or to look at medical records of an injured inmate.

Among the cases highlighted in Gennaco’s report was an incident in which a deputy thought he heard an inmate mumble something disrespectful and began punching the inmate in the head and neck. The deputy initially ignored a sergeant who witnessed the “unprovoked attack” and screamed for him to stop hitting the inmate. The department fired the deputy and suspended his partner for not telling the truth about the incident.

In another case, a deputy and a custody assistant entered the cell of a mentally ill inmate and struck him in the head with their flashlights. When they realized later that he was bleeding, they did not seek medical help. Instead, the custody assistant gave the inmate towels to clean up the blood in his cell. The injuries and the alleged attack were discovered and treated only when a deputy on the next shift noticed them.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.