Students get a last chance -- rap

Jennifer Murphy knows tough schools. She has been cursed at and threatened, has broken up fights and confiscated weapons. Still, she looks slightly queasy as she sits in her glass-walled principal’s office, staring at a huge flat-screen monitor.

A videotape is playing. It shows a teenage girl standing outside the main office of Murphy’s school. The girl glances around furtively, then hoists herself onto a counter and slides through a pass-through window, into the office.

Murphy freezes the image, then rewinds it. The girl goes through the motions in reverse, hopping down, backing away. Murphy does this repeatedly, forwarding, reversing, forwarding again, as if willing the sequence to change. It doesn’t. The girl makes the same bad decision each time.

It is not yet 10 a.m., the beginning of the school day at Media Arts Academy, a charter school in Hawthorne that calls itself Hip Hop High and exemplifies, in some ways, the promise and the challenges of the charter school movement.

It is a place where failing students get a second chance. Media Arts showers them with attention, treats them with respect, offers plenty of independence and, along the way, gives them the opportunity to lay down their own hip-hop beats and raps.

Some days, it all works beautifully. Today is not going to be one of those days.

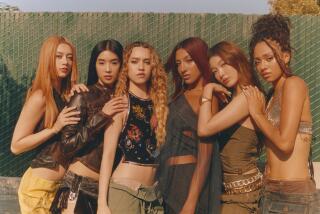

Murphy minimizes the video image, which was recorded earlier that morning. She stands, a tall, striking woman whose long red hair glides down the back of a black leather jacket. An ankle tattoo is visible.

Behind her is a cabinet, which has been rifled. Cash has been taken. The girl on the surveillance tape is the sole suspect.

“I’m going to have to talk to her,” Murphy says.

I am really friendly

I wonder if I’ll make it to my 40s.

I hear gunshots

I see myself lying on the floor

I want world peace

-- Maria Olmedo

12th grade

Media Arts was founded in 2004 and endured a couple of years of dreadful academic performance before turning a corner last year under Murphy’s leadership. Its Academic Performance Index score shot in one year from 386 -- about as low as a school can go -- to 537.

That is still extremely low, more than 150 points below the state average and 15 points below nearby Leuzinger High School, a regular public school in Lawndale. Not a single student at Media Arts scored at the advanced level in any subject included in state standardized tests. In math, not one was even judged proficient.

On the plus side, few schools have achieved such strong growth in a single year.

This year, Media Arts formed an alliance with a Minnesota school, the High School for Recording Arts, founded in 1996 by rapper David “TC” Ellis, whose career was nurtured by the rock star Prince. The idea, he said, was to provide “experiential education” built around something that urban kids loved, hip-hop music. Now Media Arts is using some of Ellis’ ideas to motivate students through music.

“A lot of these kids wouldn’t even be in school if it wasn’t for a place like this,” Ellis said on a visit for the opening day of the school year. “Traditional schools are losing, like, half their kids. It works for some, but not for a lot of them.”

Anyone spending time at Media Arts has to ask two questions: Is this working any better? And if it is, can it compensate for years of poor schooling in elementary and middle grades or for a social environment in which violence is the norm and academic achievement a rarity?

Charters like Media Arts are public schools, paid for with tax dollars but run by private organizations. California charters tend to serve inner-city neighborhoods, and many are filled with impoverished students fleeing underperforming, violence-plagued neighborhood public schools. Some of the most successful of these schools are staunchly traditional, demanding strict discipline and requiring students to wear uniforms.

It probably goes without saying that there are no uniforms at a place that calls itself Hip Hop High.

There are rules for dress: No caps, no outward expressions of gang affiliation. But in general, this is a casual place that opens its arms to students who chafed against rules in traditional schools or who were desperate for a place where they could feel safe. Like all charters, Media Arts is required by law to accept any student who applies as long as there’s space.

They are students such as Lorena Alatriste, who takes a train and two buses to get to school each morning from the Imperial Courts public housing project in Watts.

“It’s a lot different from a normal school,” she said. “In another school, they would just let you fall back, but here, they push you to do your work. They really care about you.”

And they are students such as Tyler, who operates at a significantly higher voltage than the average teen and had trouble fitting into traditional schools. (He asked that his last name not be used.) He appears to have found a place where he can get along and stretch himself creatively, although the results can be profane and disturbing.

“Tyler is absolutely amazing,” said Jacques Slade, who teaches music production at the school. “He’s like a little miniature Andre 3000. . . . He’s so creative right out of the box.”

The media arts academy inhabits a large, plain warehouse that doesn’t even try to rise to the level of industrial chic. The floor is concrete. Classrooms are arrayed along the walls of the hangar-like space, separated by chest-high partitions.

The school is tucked into a mixed industrial and residential neighborhood near the intersection of Rosecrans Avenue and Crenshaw Boulevard. Some of the nation’s most violent neighborhoods lie immediately to the north and east.

“There’s just an extreme level of violence in their neighborhoods, extreme levels of poverty,” says teacher Nasanet Abegaze.

A few minutes to 10, students begin drifting in to Abegaze’s class, logging on to their computers and quietly getting to work on personal video projects, interlacing music, video and text.

Douglas Villalta, an 11th-grader, is making a movie about a friend who was stabbed to death. Premature death is not uncommon in Douglas’ world.

“That’s the way it is, and that’s the way it’s going to be,” he says.

About 20 minutes into class, one of Abegaze’s students comes in; his excuse, not an uncommon one, is that he was at a probation hearing.

Until this fall, Abegaze taught at John Muir Middle School in South Los Angeles, which serves a similar, if younger, population in the Los Angeles Unified School District. The curriculum, she said, didn’t have much to do with her students’ lives, and she taught 160 students a day, making it hard to make connections. At Media Arts, there are only 140 students in the school, and each teacher has primary responsibility for just 20 to 25.

The challenges are enormous -- she has one 12th-grader who has never learned to read -- but so are the satisfactions.

“These are students who have been kicked out of two or three schools, for the most part, and I’m just amazed by how brilliant and creative they are,” she says.

I understand that Life is what you make it

I say that after all the Pain comes the Pleasure

I dream I’m in my baby love’s arms again

I try to be strong & overcome all fears

I hope I get to see my one n’ only very soon!

-- Maria Ponce

12thgrade

In another class across the building, Tyler slouches at his computer in a cockeyed, bright green baseball cap and blue polka-dotted sweat shirt, a resplendent, psychedelic vision of street fashion gone haywire. (He violates the no-cap rule whenever he can.) He is completing a work sheet, listening to his iPod and occasionally noodling with the computer, which displays a cover of the magazine he designs in his spare time.

He calls the magazine Odd Future, which describes the universe he already seems to inhabit, a place dominated by three primary forces (besides his mother): music, fashion design and skateboarding.

Is it possible to be 16 years old and eccentric?

It doesn’t take long to figure out that Tyler is an extremely bright kid with an old soul and a wildly creative mind. He also is attending his 11th school in 11 years.

What happened?

“I don’t really know,” he says, in a pensive, gravelly voice, which sounds like it should belong to somebody’s grandfather. “I had a couple of problems at a couple of schools. I remember at Anza [Elementary, in Torrance], I got into a little fight with another kid. . . . And then, me and my mom moved a lot.”

Tyler’s mother, Bonita Smith, says Media Arts gives him the freedom to express himself both artistically and academically. A social worker, Smith is one of few college-educated parents at the school and has high aspirations for her son. She says it doesn’t bother her that no small number of his classmates are gang members or otherwise troubled.

“I think it’s great for Tyler to be exposed to everything,” she says. “Because I want him to know what’s out there, I want him to know what’s in the real world. I don’t want him to be sheltered.”

That mission has been accomplished, as anyone can see by viewing Tyler’s contributions to YouTube, where he has posted raps -- at least one of which was recorded at school -- that embody the misogynistic, profane and violent side of hip hop.

Tyler’s class is taught by Andrea Munro, a 27-year-old second-year teacher who, at 5 feet 1, is dwarfed by most of her students. She came to Media Arts last year after working for the History Channel in New York and realizing that she wanted to make more of a difference. It has been an education.

“I had seen gang stuff on television -- I’m from Rhode Island -- but I never realized how terrible it is,” she said. Recently, she asked her students about their plans for college and career. “They said, ‘What are the chances that we’ll even make it to 18?’ ”

Like many good teachers, Munro plays a multidimensional role: surrogate mother, big sister, advocate, mentor, counselor. She is available to her students 24/7 by cellphone, and they aren’t shy about calling.

“Oh, my God, I love Ms. Munro,” gushed one girl, Rachel Ku. “She could be named the best teacher in the world, and the most caring teacher in the world.” Last year, Rachel says, she went through some difficult times, and Munro was there for her. “I was going so nuts, and . . . she would check up on me and things.”

Last summer, Munro helped Lorena Alatriste get a scholarship to Outward Bound, a transformative experience that led her to raise her sights and aim for a career as a lawyer or engineer. Now Munro is trying to help her get a scholarship to study in Europe next summer.

She is, however, absent today, and a substitute is trying to maintain order.

The students are supposed to be studying American media history, reading a short essay about the origins of the film industry and working in groups of twos or threes to answer questions on a work sheet. But they aren’t focusing.

Three girls sit at one table. Paola Marquez confesses that she didn’t actually read the essay; she skimmed it for answers. Lorena did read it, although not with any evident enthusiasm.

Paola reads question No. 4: “What were the contributions of early motion pictures?”

Lorena: “Do you like Jessica Simpson?”

Paola: “Yeah, I like Jessica Simpson.” They high-five.

Paola goes back to the work sheet -- for about five seconds.

“Oh, did you guys see ‘Pulp Fiction’?” she asks. The other girls have never heard of the movie, which came out when they were toddlers, but Tyler, hunched over his paper at another table, somehow hears them and responds, in his basso profundo: “Yeah! Quentin Tarantino! They shot parts of it right here in Hawthorne. Do your work.”

Unlike Paola and Lorena, the third girl, Maria Olmedo, is in her first year at the school, having transferred from Lynwood High.

“Compared to my other school -- they just gave you books and said, ‘Do this,’ ” she says. “What they would teach me for a year, I learned here in a week.”

Asked what she’s learned, she is momentarily nonplused. “Like, I had to do --what do you call those letters? Oh, a persuasive letter,” she says, finally. “And a PowerPoint.” She also is part of a group of Algebra 2 students who work with a math tutor.

“Right here, they show that they care,” she says. “At a regular school, I ask a question and the teachers look at me like I’m dumb.”

Ms. Munro, she says, never does that.

I’m going to start off by asking you a question.

The question is: Why?

Why do you use me as a king in a checkers game

That cannot die? . . .

You put me on this board game

To win and not give up.

Well, I see more as I grow up.

As I grow, I’m shocked.

It seems my time to die

Is on the clock.

-- Anthony Cabezas,

a.k.a NaNee

11th grade

Michael McCoy teaches in the class next to Munro’s. The school’s music and art advisor, McCoy says his top priority is to help create the kind of culture that shields students from the chaos permeating the world outside -- the gangs, the violence, the drugs, the racism.

“You need that safe home feeling before you can ever start enriching your mind,” he says. “So we’re starting there.”

Those words have barely left his mouth when his attention snaps across the building. Two students are fighting. One is advancing, his arms rotating in a tight blur, the other retreating slowly as the fists whack him like fan blades.

McCoy -- and every other teacher in the building -- breaks into a run toward the melee. Meanwhile, two other students, each a friend of one of the fighters, move in to help their buddies and wind up squaring off against each other. The teachers seem uncertain what to do.

Murphy appears out of nowhere, lunges into the scrum and grabs one of the fighters in a bear hug from behind. Teachers grab the other combatants.

Other students have gathered to watch. The fight, the first of the school year, has been both exciting and frightening. No one was badly hurt; no weapons were drawn. But these kids know how easily a fight can spin out of control.

Tyler is asked what happened.

“I don’t know, somebody said something wrong,” he says. “But they’re going to get kicked out, most likely, because they don’t want none of that here.”

Back in class, the substitute is getting annoyed. Few students are doing their work. Most are chatting quietly, or watching YouTube or messing with their MySpace pages. He reminds them that he’s in charge and that he expects them to work. They just stare at him.

As soon as he goes back to his desk, the students start chattering. “If he wants us to respect him, he needs to respect us,” says Rachel, who has bleached blond hair with dark brown ends. “When he said to us, ‘This is my class,’ I wanted to say, ‘No it isn’t. This is our class.’ If you want to get respect, you have to give it.”

Phil winden and Jacques Slade are upstairs, in the recording studio. Winden, 42, is a tall, burly white guy with a nearly shaved head and a close-cropped beard. Slade, 31, a musician and composer, is a bit smaller, African American, dressed much like the kids with baggy jeans, an oversized T-shirt and hoodie.

The studio consists of two rows of Macs, where students create tracks on GarageBand and eventually work up to Pro Tools, the industry standard. There is also a glassed-in studio with a professional soundboard.

Students are allowed to use the studio only after they receive passes from their teachers, usually for completing their work and having good attendance. Eventually, Winden says, they will learn “music production from A to Z.” Few may choose music as a career, but those who do will have received the equivalent of a trade school education.

Soon, Tyler enters the room, wearing his green VIP pass, and takes a seat at a keyboard with a computer monitor. He begins to play, stroking the keys with long pianist’s fingers.

Tyler can seem childlike at times. But now, he looks like a seasoned professional. Lips pursed, head bobbing, his fingers expertly lay down chords on the keyboard, then switch to the mouse to do the mixing.

He is asked what he’s doing. “I don’t even know,” he says. “Yesterday, I was up here, just playing, and I just came across this crazy drum pattern. . . . And when I made it, I just saw some crazy colors, like lime green and pink, like real ‘80s colors like Prince would play or something. You want to take a listen?”

He has just overlaid electric piano, a bass line, xylophone and brass, he explains. Handing over the headphones, he adds, “Just remember: Prince.” The song sounds like jazz-infused techno, with a repetitious drum pattern and dreamy piano lines. With a hint of Prince.

Downstairs, Murphy is in her office. The day is winding to a close. She looks exhausted. She has suspended the four students who were fighting -- and will eventually expel two. All of them, she says, were crying and begging to be given another chance. “All four of those boys are kids I absolutely adore. And they made a really bad mistake,” she says.

And then there was the girl who was caught on the videotape breaking into the office. Murphy confronted her. “She started crying,” Murphy says. “She said she didn’t steal the money. She said she took a pen. . . . She’s a really good girl. She’s trying.” She will remain at school.

Murphy wrestles with issues like this every day, and she admits that it is wearying. Teachers and students alike say she has saved this school, or at least is trying. It is a bit of a high-wire act, but Murphy insists that the students keep her going.

“What they walk through to get to school makes them heroes. And I want to honor them for that,” Murphy says. Are they getting a good education? “We keep raising the bar.” She lifts her hand as high as it will go. “Is it this high? No,” she says. “But it will go higher.”

“What happened today,” she continues, “is not what these kids want to be. There are enough stereotypes about their age and their ethnicity and where they live.” She will use today’s setbacks as a teaching tool, to rally the students around the idea that they can be better, that they must be better, that deep down they are better.

“This,” Murphy says, “could be a catalyst to begin a movement.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.