Johnny Grant, 84; Hollywood’s biggest promoter

Johnny Grant, who visited Hollywood in 1943 as a star-struck serviceman and returned to carve out a niche first as a radio and television personality and then as its honorary mayor and foremost booster, died Wednesday at the age of 84.

Grant appeared to have died of natural causes, authorities said. Shortly before 7 p.m., an associate found him unconscious in the penthouse of the Hollywood Roosevelt Hotel, where Grant made his home. City paramedics declared him dead at the scene, police said.

Hollywood Chamber of Commerce President and Chief Executive Leron Gubler said Grant was getting over a back fracture, but otherwise was active and in good spirits.

“It’s a shock to all of us,” Gubler said. “His health had been up and down the past year or two, but nobody expected this.”

In a seven-decade career, Grant hosted an early television game show, covered Hollywood on radio and TV, worked as a disc jockey, and acted in movies and on the small screen. But it was as Tinseltown cheerleader that he became a celebrity himself.

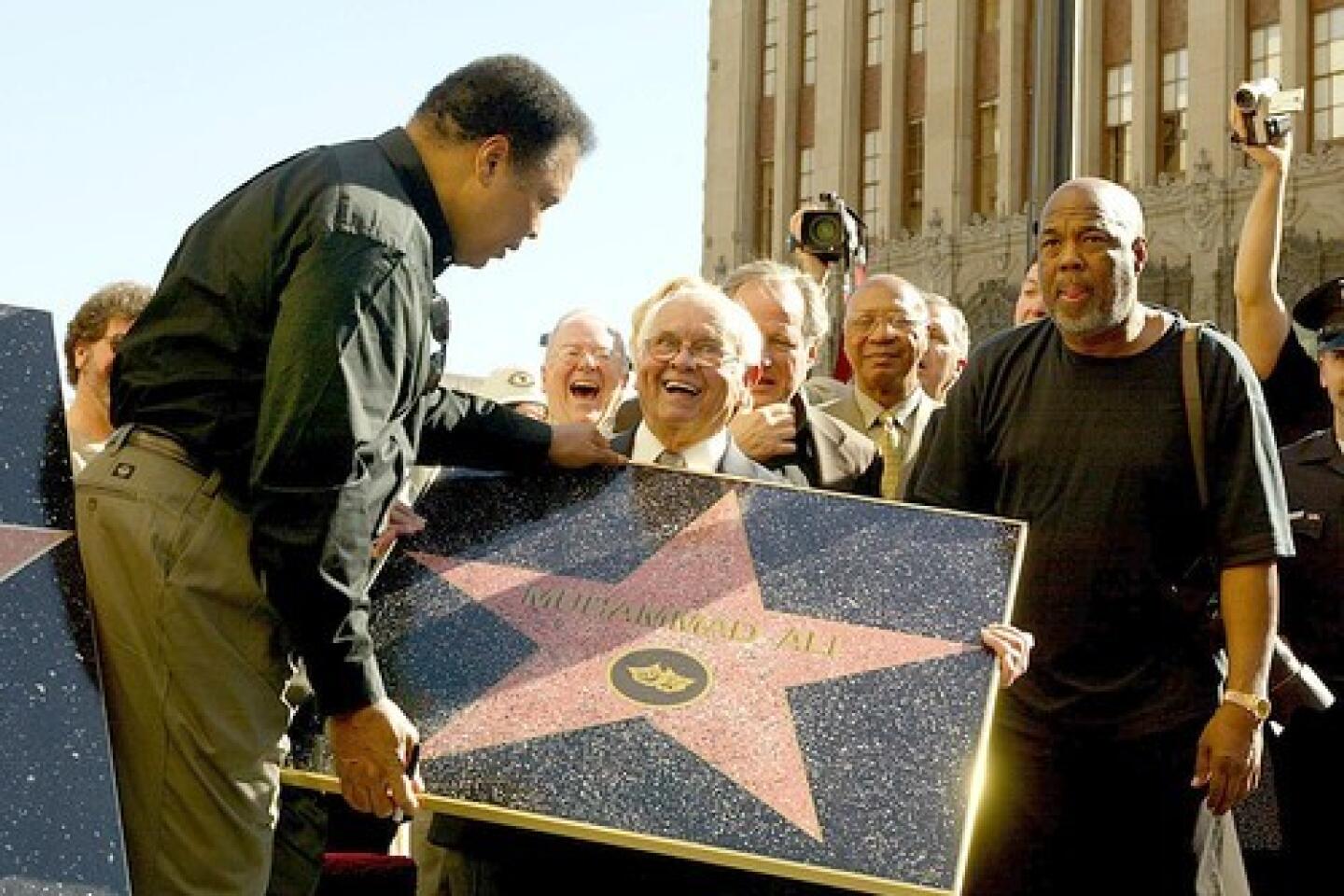

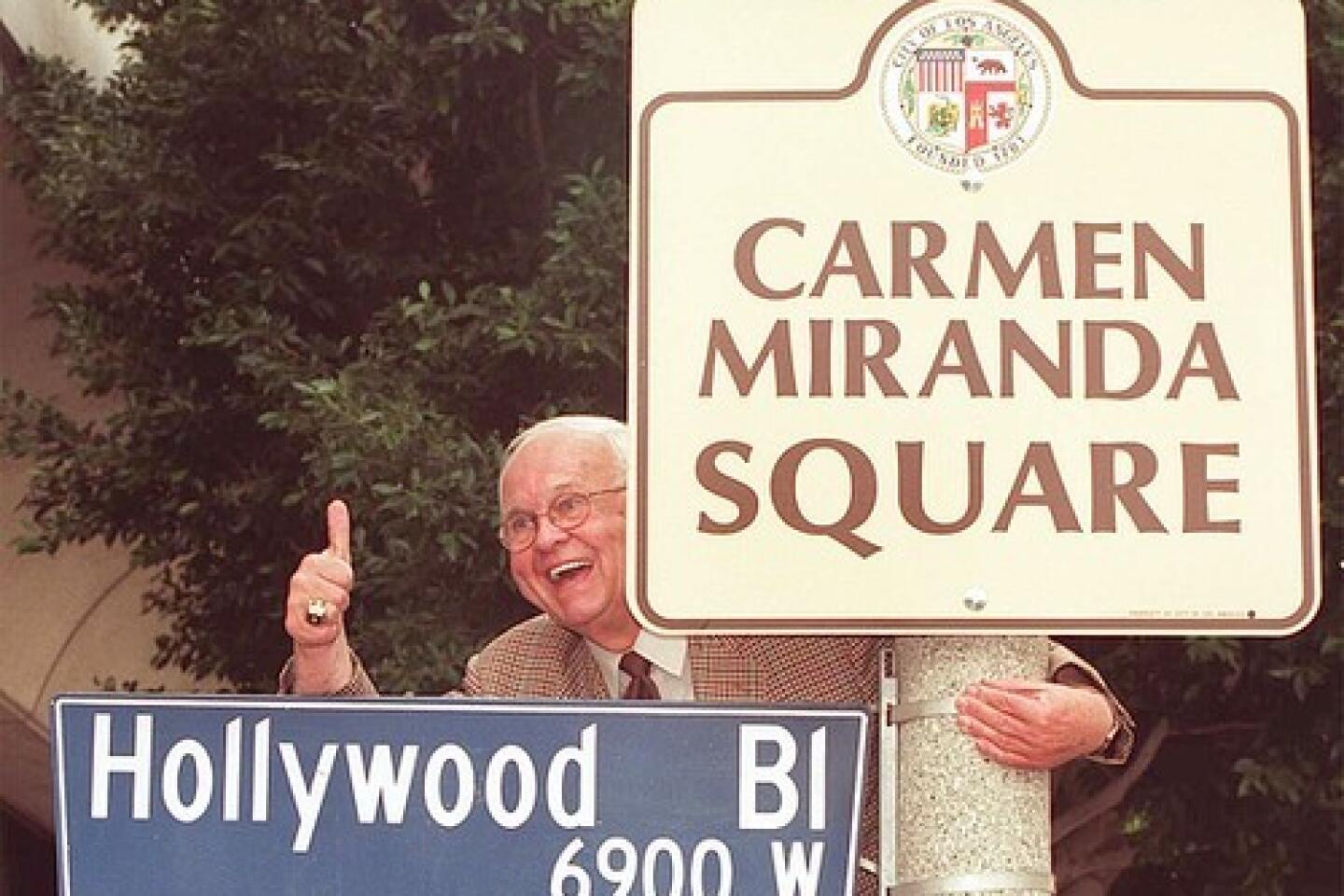

Grant hosted hundreds of Walk of Fame inductions, being photographed alongside a succession of stars as their names were immortalized on the sidewalks of Hollywood. He had produced the now-defunct Hollywood Christmas Parade since 1987 and, like his friend Bob Hope, took Hollywood to the troops, emceeing shows in Guantanamo Bay, South Korea, Vietnam, Lebanon and Bosnia. In November, he made his 60th trip overseas to entertain troops.

“He had a great time,” Gubler said. “Helping people, that’s what he thrived on.”

He seemed always to remember that millions of people were in awe of the name Hollywood, just as he was as a boy growing up in Goldsboro, N.C.

“It’s a magic word all over the world,” he told Times columnist Jack Smith in 1987, the town’s centennial year.

Grant sought to preserve that magical image long after most of the stars and studios had moved elsewhere and the streets became the haunt of prostitutes, addicts and the homeless. His prescription was always the same: put on a show.

In 1980, when he took over as Walk of Fame chairman, “you couldn’t get anyone to come to Hollywood Boulevard,” he told a reporter in 1997. “So I said, ‘Why don’t we really put on a big show when we have a Walk of Fame ceremony.’ We had planes fly over, bands, etc.”

His Hollywood’s Welcome Home Desert Storm Parade in 1991 for troops who fought in the Persian Gulf War was a rolling, marching, flying extravaganza of military personnel and equipment that starred a Patriot missile. Grant reported attendance at 1 million, the same figure that he gave year after year for the Hollywood Christmas Parade. When a Times reporter applied a formula used by the U.S. Park Service to estimate crowds and informed Grant that no more than 500,000 people could fit along the Desert Storm parade route, he admitted his exaggeration.

“You know Hollywood,” he said. “It’s hype.”

Some criticized Grant for his P.T. Barnum tendency. Times columnist Patt Morrison called him “orotund” and compared him to “a type that once peopled the L.A. landscape from the real estate land rush into the 1960s.” But others admired the frankness that accompanied his glad-handing style.

“That’s what’s refreshing about him,” Larry Kaplan, former executive director of the Hollywood Chamber of Commerce, once said. “He doesn’t portray himself more seriously than he is.”

Grant’s own star is in the walk’s choicest location -- outside Mann’s Chinese Theatre. The master of self-promotion organized the ceremony and said its extravagance landed him the job as Walk of Fame chairman.

His handprints and footprints were added to the theater’s famed courtyard in a 1997 ceremony that included a flyover by World War II-era planes. Grant arrived in a rickshaw accompanied by a police motorcycle escort, a marching band and two hook-and-ladder firetrucks, their ladders raised to form an archway.

Grant was short in stature, with a deep voice that helped him land his first show business job -- working as a radio announcer in his hometown after high school graduation. He was fond of saying that he never worried about his height after seeing Mickey Rooney in “Boys Town” and resolving, “if that little squirt can make it, so can I.” Rooney, incidentally, was on hand for Grant’s Walk of Fame induction.

After World War II service in the Army Air Forces -- he hosted a radio show for the troops and did advance work for bandleader Glenn Miller’s troupe -- Grant worked as a radio reporter in New York. It was there, in 1946, that he hosted a TV game show called “Stop the Clock.”

But he soon returned to Hollywood, making good on his vow that “I was going to be a part of it somehow.”

Most of Grant’s on-air work was for Gene Autry, who owned KTLA-TV and KMPC-AM. The two had met during the war. Grant hosted a celebrity interview show and reported Hollywood news on KTLA, and was the disc jockey on KMPC’s long-running “Freeway Club” program. He served as KTLA’s director of public affairs from 1971 to 1992. The two men’s association lasted 42 years, and it is no coincidence that Autry has five stars on the Walk of Fame, more than anyone else.

The mayor of Hollywood loved being before an audience. When a restaurant co-owned by Jack Klugman created a pizza in Grant’s honor, the main ingredient was ham. Grant estimated that he had been master of ceremonies at more than 5,000 events, ranging from Walk of Fame inductions to charity soirees to adopt-a-pet promotions to 20 Stop Arthritis telethons. In 1976, Grant produced and emceed Operation Understanding, where he and 51 other well-known people disclosed their alcoholism.

Grant and co-hosts Bing Crosby, Bob Hope and Frank Sinatra put on what is believed to have been the first telethon, which raised funds in 1952 for the U.S. Olympic team.

Over the years he befriended many political leaders, most of them Republicans. Grant hosted events for every GOP president from Dwight D. Eisenhower to George H.W. Bush.

During his career Grant received two Emmys and the Academy of Television Arts and Science’s Governors Award. His acting roles, usually as a reporter, disc jockey or TV host, included the films “White Christmas,” “The Babe Ruth Story” and “The Oscar.” He appeared on TV’s “The Lucy Show,” among others.

Grant never married and had no children.

It was the Hollywood chamber that, in 1980, named him “mayor for life.” Grant enjoyed saying that it was “the best job in town,” and that he wanted his ashes strewn under the Hollywood Sign.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.