Ailments diminish, air improvements are notable after oil field closes

Maria de la Cruz is doing something these days she says she hasn’t done in years. She lets her grandchildren play in the living room — and even opens the windows to let air circulate.

Ever since Allenco Energy Inc. shut down its oil field across the street from her apartment in University Park, “it feels like a new life for us,” de la Cruz, 48, said in Spanish. “We used to keep the windows closed tight and made the children play in a back bedroom so they wouldn’t breathe those chemicals. But since the company closed down, the kids haven’t been sick once.”

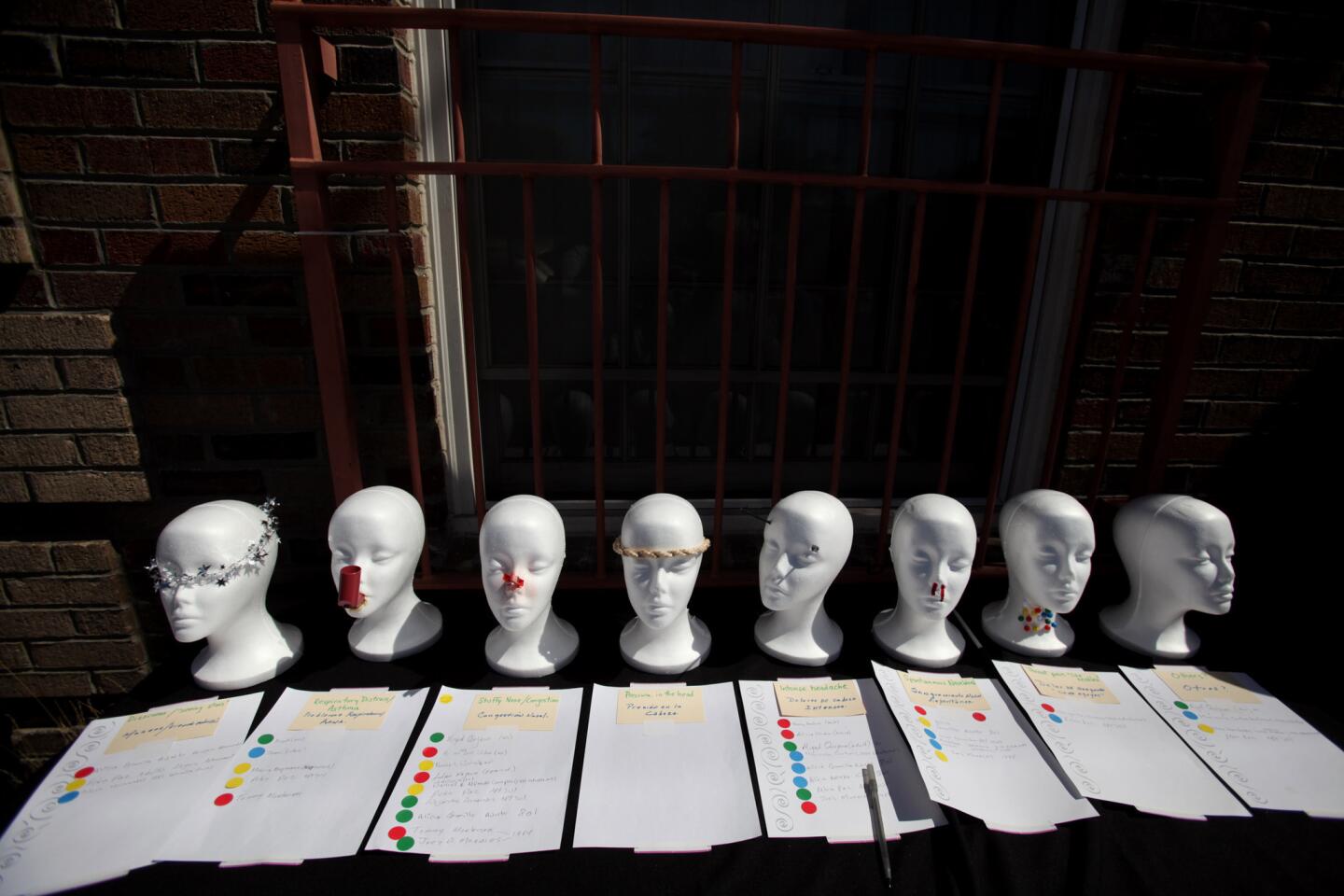

Less than two months after operations were suspended at the urban oil field, located in the South Los Angeles neighborhood about half a mile north of the USC campus, formal complaints of respiratory ailments and nosebleeds have all but disappeared.

Allenco hopes to resume production within a few months, after making improvements. But a lawsuit filed against the facility by the Los Angeles city attorney’s office last week brought hope of permanent relief from the noxious fumes that have plagued the community since Allenco boosted oil production by 400% in 2010.

The lawsuit filed in Los Angeles County Superior Court accuses Allenco of ignoring evidence that its emissions were the source of debilitating ailments: nosebleeds, headaches, fatigue and asthma. The complaint seeks a permanent injunction against the oil extraction operation until it no longer poses an imminent threat to public health.

“We are surprised by the filing and have retained counsel to respond,” said Peter Whittingham, a spokesman for the company.

Local activists have produced a video seeking assistance from Pope Francis in preventing Allenco from resuming operations under any circumstances. The video was shot on a rooftop overlooking the two-acre parcel Allenco leases from the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles. It is narrated by 13-year-old Nalleli Cobo, who lives across the street and says she has suffered chronic nosebleeds, stomach pains and headaches for years.

“There are many other things that this land can be used for that would be beneficial to the community,” she says in the video. “For example, a park, community garden or affordable housing. Certainly not a use that makes people sick.”

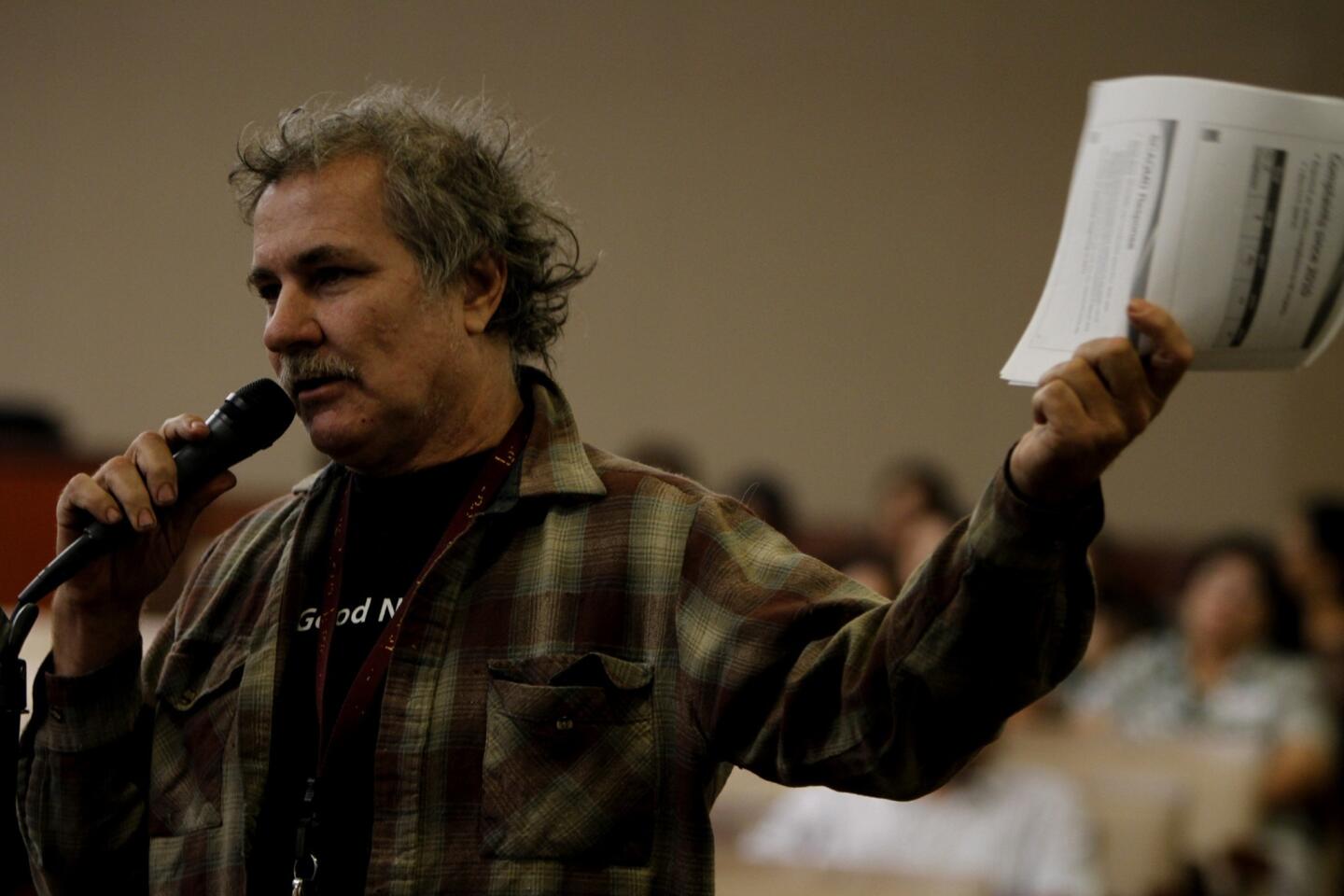

Odors from Allenco’s field prompted at least 260 complaints to air quality officials from area residents in the past four years. U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.) called on Allenco to suspend operations pending completion of several ongoing investigations. The company complied in November.

“This shutdown has tangibly improved the quality of life for these people,” Boxer said in a recent interview. “The oil operation should go elsewhere.”

Lydia Hewlett, 38, alleges that an industrial accident at Allenco contributed to her losing her job as director of academic advisement and study abroad at the Doheny Campus of Mount St. Mary’s College, which sits adjacent to the urban oil field.

On Jan. 25, 2011, the campus was overwhelmed with toxic odors, according to the city attorney’s complaint. Thirteen people were treated for symptoms including nausea, asthma and a nosebleed, college officials said.

The problem was due to a leak of production water mixed with a rust inhibitor and hydrochloric acid, officials said.

Hewlett requested that she and her staff of four be relocated elsewhere on campus because of what she described as “waves of fumes.” She said college officials instead “advised us to open the door and let in fresh air, which, under the circumstances, didn’t make sense.”

A week after the incident, college officials assured the campus community that the South Coast Air Quality Management District and a private consulting firm had determined the fumes were not toxic.

Unconvinced, Hewlett urged her staff to report their situation to the Division of Occupational Safety and Health. She now believes the complaint to Cal/OSHA was the prime reason she was fired in 2012, according to a wrongful termination suit she has filed against the college.

Mayra Abrams, 33, who is not involved with the lawsuit, said in an interview that she quit her job as associate director of academic advising because of Hewlett’s dismissal and the college’s seeming lack of preparation for such an emergency.

“Mount St. Mary’s felt like the ‘Twilight Zone,’” said Abrams, who is completing a master’s program at the college.

Chris McAlary, vice president of administration and finance at the college, said he trusted the AQMD’s assessments. “I was leaving it in their hands to crack the whip on Allenco,” he said.

Allenco paid to move college air-conditioning intake vents that were near the oil site. The neighborhood was never notified about the accident because the odors were never considered a health threat, air district and college officials said.

Jose Salizar, 83, who shares an apartment with de la Cruz, fears further health risks if Allenco is allowed to reopen.

“I’ve been coughing since I moved here 10 years ago and my doctor said it’s probably because of those wells,” said Salizar, who uses a walker. “After the wells closed, the bad smells and the coughing went down.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.