L.A. to list structures that could be at risk in quake

The Los Angeles City Council on Wednesday took the most aggressive action on earthquake safety in nearly three decades, instructing building officials to find apartment buildings vulnerable to collapse in a major temblor.

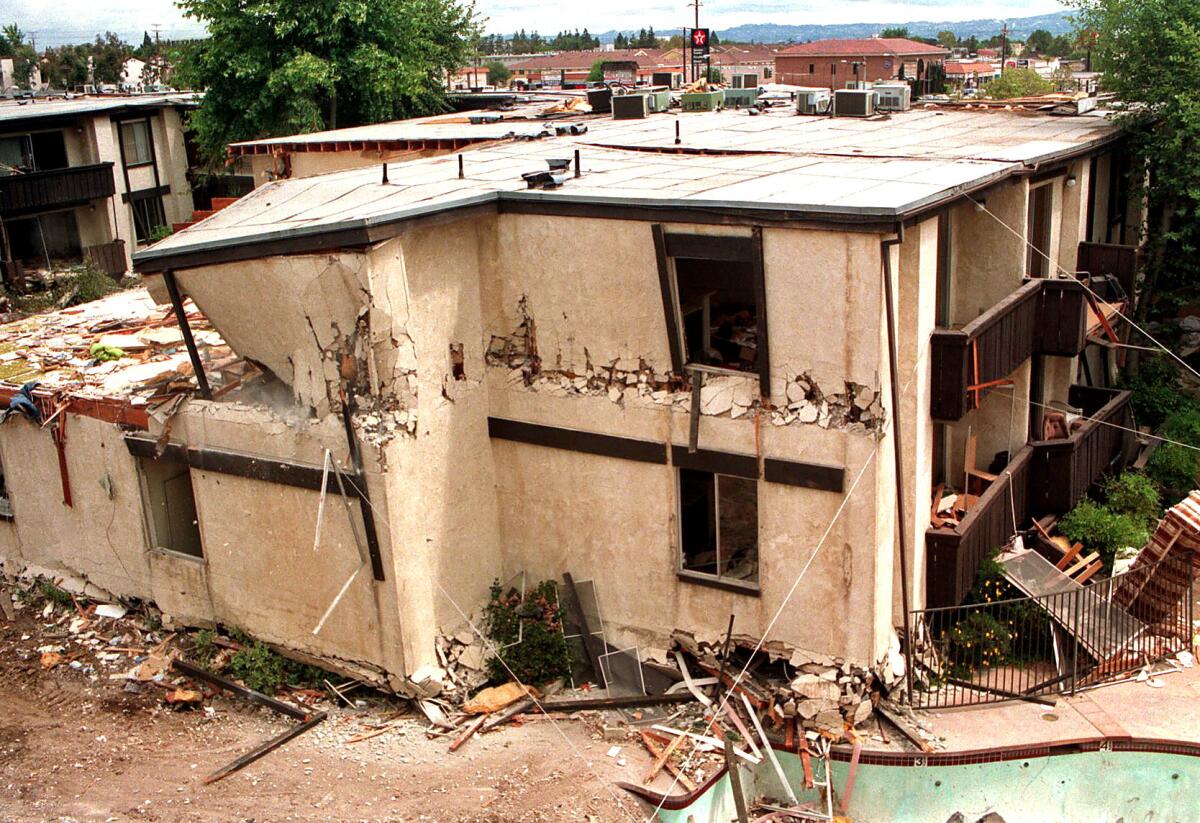

L.A.’s survey would focus on the thousands of wood-frame buildings similar to the Northridge Meadows apartment complex, which collapsed and killed 16 people during the 1994 earthquake.

Until now, the city has rejected efforts to launch a citywide survey to figure out which structures might be vulnerable.

“This is something we should’ve done 20 years ago,” said former Councilman Greig Smith, who pushed unsuccessfully for seismic safety measures. “An inventory will allow you to assess what the risks are. And it hasn’t been done.”

The city has not decided what to do once it compiles the list. But seismic experts and policymakers say making a list of buildings that could be vulnerable is a necessary first step.

“It’s so key,” said L.A. City Councilman Tom LaBonge. “You have to have the data to know how many buildings are like this and where they are. And to give us a kind of road map of what we can do to improve these buildings.”

The action marks the first in what is expected to be several seismic safety measures at City Hall. Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti said earlier this year that he supports some type of mandatory retrofitting of older buildings that have a risk of collapse in a major earthquake. He also said he wants buildings across Los Angeles to be graded for their seismic safety.

A Garcetti spokesman said the mayor supports the inventory of “soft-story” wooden apartments.

Soft-story buildings have weak first floors because they are often built over carports and held up with slender columns.

No city data exist to easily identify which structures are wood-framed and soft-story, said Ifa Kashefi, chief of the engineering bureau at the L.A. Department of Building and Safety. The survey would focus on structures built before 1978 with at least two stories and at least five units.

The city’s housing department provided addresses of 29,226 apartment buildings constructed before 1978, according to Kashefi’s report in November. Staffers would then need to use mapping programs to narrow down which apartment buildings need further field inspection.

The report estimates that 20% of the 29,226 buildings, or about 5,800, will be soft-story buildings, and an additional 11,690 buildings will need to be inspected on site to determine whether they are soft-story buildings.

Three people would be hired to work for the building and safety department to create this inventory. The project would take about 18 months, officials said.

L.A.’s move comes about a year after San Francisco passed a landmark earthquake safety ordinance that requires the city’s wooden apartment buildings to be strengthened.

San Francisco spent about six months scrubbing their data from 70,000 to 6,000 buildings that needed further inspection, said Patrick Otellini, who runs the city’s earthquake safety program.

Beginning in September, owners of the 6,000 buildings were ordered to send in a report on their building by a licensed professional. About 60% of these buildings have been screened to see if they should be included in the city’s retrofitting program, Otellini said.

In the 1980s, Los Angeles required owners to retrofit or demolish roughly 8,000 brick buildings deemed seismically unsafe.

But efforts to do the same for other types of at-risk buildings such as wood-frame and concrete structures stalled amid concerns from tenants and property owners over who would pay for the retrofitting.

Beverly Kenworthy, executive director of the Los Angeles division of the California Apartment Assn., said she is not opposed to the wood-frame building inventory. But she said the city needs to come up with financial help for owners to pay for retrofitting such as tax credits or access to low-interest loans.

“When the list comes out, we need to make sure property owners have a place to go or at least know what their options are,” Kenworthy said.

City officials have been exploring a possible state bond measure that would provide funding to cities for retrofitting and other seismic work. Others have raised the possibility of tax incentives for retrofitting.

Soft-story wood-frame apartments are one of several types of buildings experts say are vulnerable to collapse in a big quake. Another class of buildings that pose particular risks in Los Angeles is older concrete buildings. A Times story in October reported that by the most conservative estimate as many as 50 of the more than 1,000 older concrete buildings in the city — those built before 1976 — would collapse in a major earthquake, exposing thousands to the risk of injury or death.

Since the Times report, the city has also been studying ways to identify and strengthen those buildings.

Santa Monica on Tuesday approved a more sweeping response than L.A., greenlighting a plan to hire a top earthquake engineering firm to identify all seismically vulnerable buildings in the city.

Santa Monica officials have already begun combing city streets to assess wooden apartment buildings — and some were retrofitted in the years after the 1994 earthquake, building official Ron Takiguchi said.

The city will now spend about $91,500 to hire Degenkolb Engineers to help identify all older concrete buildings as well as steel-moment-frame and “remaining types of seismically hazardous buildings.” The work is expected to take about six weeks.

The survey does not include single-family homes and will focus on buildings constructed before 1996.

Once the buildings have been cataloged, owners would eventually be notified and given a chance to show that their structure does not need seismic strengthening. Buildings determined to be a problem would have to be retrofitted.

Santa Monica’s move comes 20 years after the city passed laws requiring retrofitting of concrete, steel and wooden apartment buildings that are vulnerable to collapse during shaking.

The Times reported in November that the city stopped implementing the law some years later. Officials acknowledged that they could not find the list the city had created of buildings that might be at risk.

Mayor Pro Tem Terry O’Day said the inventory creates a valuable “baseline” for city officials to know where to focus earthquake safety efforts.

“We don’t want to drag our feet on getting this work done,” O’Day said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.