Border crossers face high risk in South Texas

FALFURRIAS, Texas — The South Texas sun had scorched the woman’s face. Flies swarmed over her lips. Under a nearby mesquite plant, a plastic water jug lay empty.

Brooks County Chief Deputy Sheriff Urbino Martinez picked it up and walked back to a group of officials gathered around the sprawled body of the dead migrant.

“She got left behind for some reason,” he said. “Either she got ill or she just got tired and they left her, knowing very well she wasn’t going to get out of this area.”

Justice of the Peace Roel Villarreal noticed that the woman’s pants were pulled down around her hips, and her shirt was wrapped over her shoulders — signs of the woman’s desperate struggle to cool down, he said.

“When it’s damn hot, that’s what you do before you die,” Villarreal said.

Across the desert expanses of California and Arizona, thousands have perished over the years while attempting to cross illegally into the United States. Now another region, this one in Texas, has become a lethal magnet for increasing numbers of migrants.

Many of these deaths occur as they try to make it through the vast ranch lands that surround a Border Patrol checkpoint on U.S. Highway 281, some 70 miles north of the border. It is the last obstacle for migrants trying to get to Houston, so they attempt to go around it by the hundreds every night.

The Rio Grande Valley recently surpassed the Tucson sector as the area with the most migrant arrests. The surging traffic has besieged border agents at the once-relatively tranquil checkpoint near the small town of Falfurrias. It also illuminates one of the major obstacles to a comprehensive immigration overhaul being debated in the Senate.

Republican Sen. John Cornyn of Texas, who visited the region in May, has expressed reluctance to support any bill that would not guarantee a 90% arrest rate of all illegal crossers, including a proposal unveiled Thursday that would double the size of the Border Patrol. He has cited the growing death count as evidence that the border remains out of control at the southern tip of Texas.

“As a policymaker, I have a responsibility to find real solutions to these issues that are all too familiar to Texans,” Cornyn wrote in an op-ed published by Fox News. “Anything less only perpetuates this grotesque human tragedy playing out every day on American soil.”

People trying to circumvent the checkpoint fail with alarming regularity. So far this year, 31 bodies or sets of human remains have been found, including the 22-year-old Honduran woman whose body Martinez retrieved in April.

Last year the remains of 129 people were discovered, a record that contributed to the Rio Grande Valley area of Texas becoming the second-deadliest crossing region, behind the Tucson area. Overall, 463 migrants died last year trying to cross the Southwest border, according to the U.S. Border Patrol.

Officials and ranchers estimate that hundreds more have probably died in Brooks County, but their bodies lie undiscovered on the cattle and hunting ranches, some of which are barren expanses larger than San Francisco.

Some believe the area’s relative lack of border infrastructure and staffing have lured crossers from more fortified regions, such as California and Arizona. Others point to geography, saying that South Texas is the nearest U.S. border for tens of thousands of Central Americans fleeing crime and poverty. People from countries other than Mexico — many from Guatemala and Honduras — now comprise most of the arrests in the region.

Getting across the Rio Grande is just the first step. Migrants hole up in stash houses in the McAllen area, then board vehicles that take them north. A few miles south of the Highway 281 checkpoint, where a sign reads “Smuggling illegal aliens is a federal crime,” the cars stop and the migrants spill out. Collapsed fences and broken branches mark the way into the ranches, including the fabled King Ranch. The migrants follow their smuggling guides north beyond the checkpoint, then board vehicles that take them to Houston.

The trek ranges from 15 to 30 miles, a relatively short distance compared with the days-long hikes migrants endure to reach Tucson or Phoenix farther west. The terrain isn’t desert, but it is perilous.

The ranch soil is sandy, sapping strength from the hardiest of legs. With no mountain peaks or unique terrain features to guide the way, migrants trudge through brushy pastures and clusters of mesquite and oak trees not realizing they’ve been walking in circles. Summertime temperatures regularly top 100 degrees.

“I don’t think they know how dangerous it is to come across here,” said Presnall Cage, owner of a 43,000-acre cattle ranch where the remains of 16 migrants were discovered last year. “They just don’t have a clue how tough this country can be.”

Cowboys and ranch hands going about their daily chores have learned to recognize the signs of a death. Circling red-headed vultures are one, but there are others. Thomas Schacharl, a ranch hand on Cage’s property, once came upon a pair of shoes placed neatly on the rutted road he was driving on. Nearby under a tree was a body.

Schacharl, 59, said he has been alerted by other signs, including brush piled on the edge of the road or clothing hanging from a branch. “Either people leave them as a sign to slow down and look around, or a person has thrown it out there, hoping somebody will find them,” Schacharl said.

Local officials struggle to keep up with the rising death toll. Brooks County, population 7,200, has no medical examiner’s office. Bodies have to be taken 80 miles to a mortuary outside McAllen. Missing persons investigations sometimes begin and end at the scene.

Martinez, the chief deputy sheriff, once found a phone on a dead 21-year-old man.

“I called and a woman answered,” recounted Martinez, who proceeded to give her a physical description of the body. “She said it was her son.”

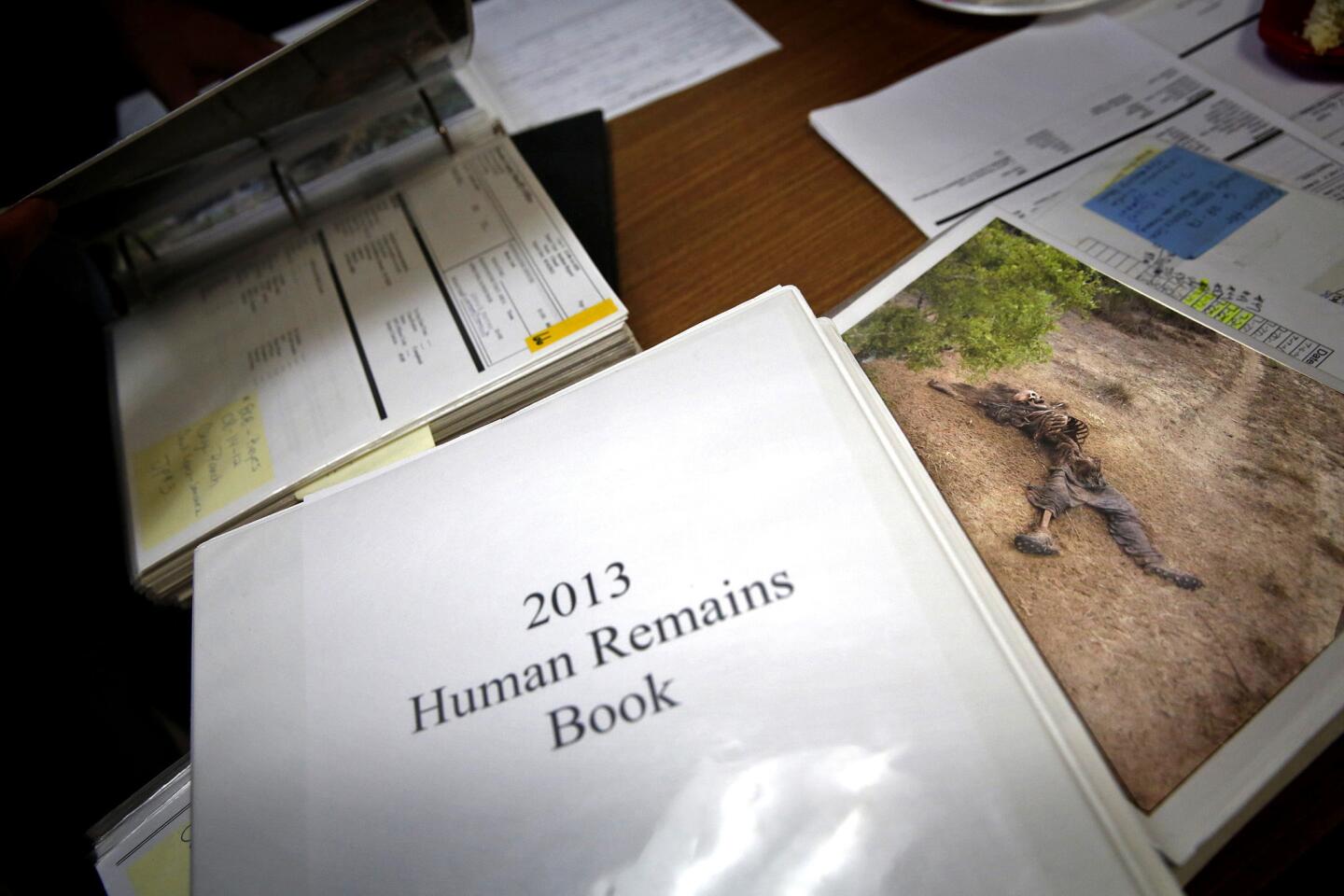

Scores of bodies and sets of human remains are unidentified. The grisly photos of animal-gnawed bodies, scattered bones and death-frozen faces fill three binders in Martinez’s office. He gets calls from people across the country and Latin America searching for loved ones. Migrants who remain unidentified end up in the town’s cemetery.

Tiny aluminum grave markers with the barest of details sit atop the mounds of dirt: “Unknown female/male,” “Skull case,” “Bones, 7/15/12.”

Over nine days in May at the cemetery, college students dug up the remains of 63 unidentified migrants. They were placed in body bags and taken to Baylor University so researchers can start taking DNA samples for a missing persons database.

With the long summer ahead, many expect the cemetery to start filling up again. Longtime rancher Lavoyger Durham said the rhythms of nature in the once-tranquil scrublands seem permanently altered. The presence of buzzards or wild hogs used to mean the creatures were feasting on a raccoon or stray calf. Now, Durham said, people see scavengers and think another human being has fallen.

“We accept it as a way of life,” he said. “You know it’s going to keep on going on.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.