Resurrection story inspires on Prophet’s campaign trail

As he campaigns for a state Assembly seat, Prophet Walker, 26, is building on his rise out of L.A.’s Nickerson Gardens.

The kids at Compton YouthBuild can be a tough audience. Many come from broken homes, flunked out of multiple schools, even spent time in jail.

By the last day of Black History Month, some at the alternative school — which looks boarded shut from Compton Boulevard — had gotten their fill of talk about hope and perseverance.

On this late Friday afternoon, though, a tall young man strode into their big multipurpose room and flashed a flawless smile. He looked a bit like the rapper Drake. Or so said a girl near the front, giggling.

When the visitor began, "How many people here are familiar with Nickerson Gardens?" some of the students stopped mugging and poking one another. They not only knew the housing project where their guest came up, they knew other young men not unlike him whose mothers struggled with addiction, who had children while still nearly children themselves, who had let violence win them over.

But his story didn't end like most. He found a way to keep learning while behind bars, went to college, then got a job overseeing big-ticket construction projects. He told the students of knowing Kendrick Lamar from back in the day and how he recently visited the hip-hop star backstage at one of his shows. Hearing that, one boy in the audience whistled in admiration and exclaimed: "Damn!"

Not only had their visitor played fate for a fool, he had a name that seemed plucked straight from a Spike Lee drama: Prophet. Prophet Walker.

"A lot of people who came from the 'hood don't do anything. But he came back," student Jonathan Chase Butler said after Walker's talk. "He is trying to speak to us and inspire us, and I see I can actually push forward and keep going. That is huge."

Now Walker, just 26, is trying to build on his unlikely story. With no experience in politics or government, he's running for the California Assembly, hoping to represent a district that stretches from South L.A. to Compton, Carson and a slice of Long Beach.

Such is the power of his resurrection tale that actor Matt Damon has donated to his campaign and television pioneer Norman Lear sponsored a fundraiser.

His high-powered supporters tend to focus on Walker's inspiring rise out of bleak beginnings. As he steps onto a bigger public stage, though, he will also have to address more directly what happened during his fall.

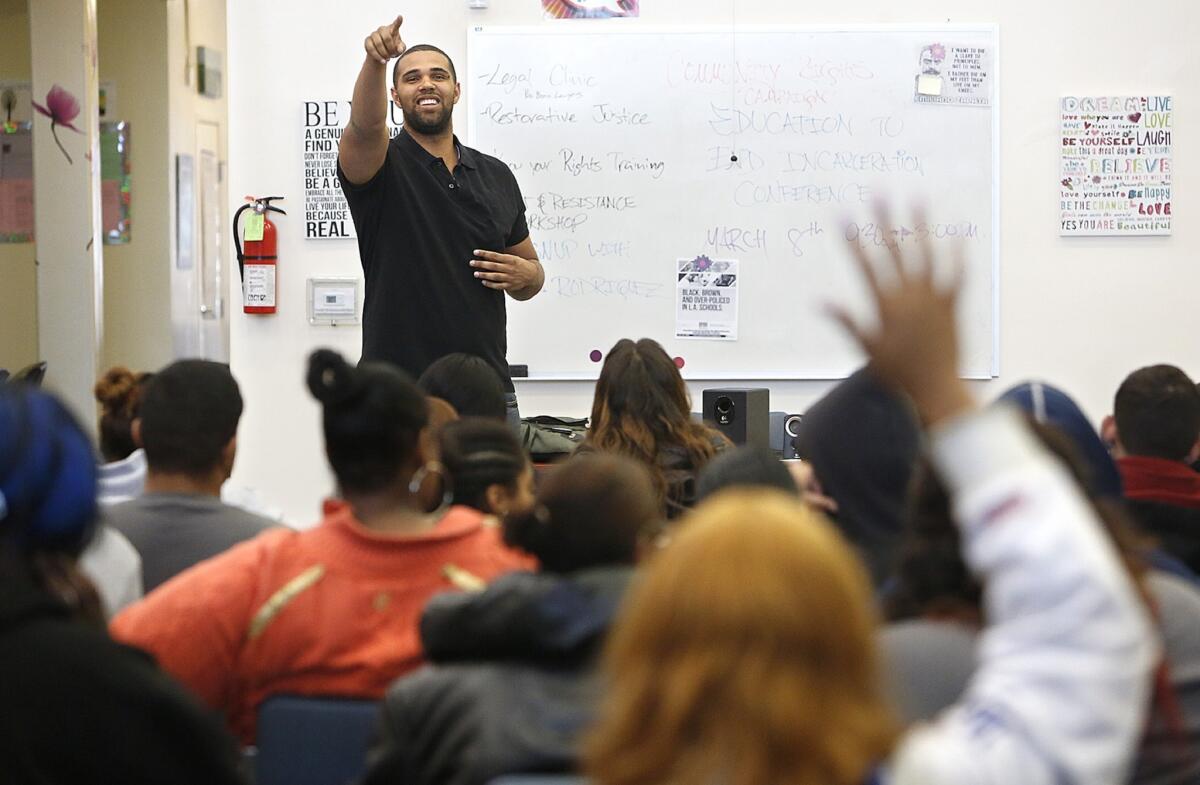

Prophet Walker, a candidate for state Assembly from the Carson/Compton area, takes questions while speaking to students at Compton YouthBuild. A big part of Walker's pitch for state office is that he will be a role model for young people on how to turn their lives around.

Walker's story begins in Nickerson Gardens, one of Watts' most notorious housing projects. It got so bad in the 1980s, police barely dared to venture among the sketchy, gang-ridden low-rises.

Young Prophet carried an added burden. He was just 6 and his sister 4 when their mother left them one day to forage for a fix. She never came back, and the kids landed with their father, Nathaniel.

Although his father was a dependable provider, Prophet struggled. Bused to Reseda High School, he failed many classes and got suspended twice, court records show. In early 2004, at just 16, Walker and two companions stole $20 from a man who had stopped at an ATM near USC.

His arrest and probation inspired a brief turnaround. Walker switched to an alternative school, earned mostly A's and B's and received citations for leadership, including a commendation from L.A. City Councilman Bernard Parks.

Eight months later he was back in trouble — and this time, it was much worse. Walker and two other teenagers robbed three young men over two days, all of them in or around MTA transit lines, authorities charged. One teen menaced the passengers with a dummy .45-caliber pistol. Walker joined the gunman in beating one of the victims badly — breaking his jaw in three places and taking his CD player, sheriff's investigators said.

A lot of people who came from the 'hood don't do anything. But he came back.”— Jonathan Chase Butler, student

Walker recalls the shock, a few months later, of being sent to adult court because of what a judge deemed the sophistication and severity of the crime. He pleaded guilty to the first of the robberies, while the other two counts were dismissed, and he got six years in state prison. "I remember thinking, 'I should be at the prom or with my daughter or something other than this. I am not a criminal.'"

He has offered multiple mea culpas for his youthful errors, especially the beating. "The stupidest thing I ever did," he calls it.

But in some previous public appearances and in his campaign literature, Walker's version takes some of the onus off his younger self. He has said that he "got into a fight" the day of the beating. He said he merely asked for the time from a Latino passenger, who responded with profanity and a racial slur, touching off a brawl. The purported provocations are not reflected in police or court records.

If his three opponents in the Assembly race — Long Beach City Councilman Steve Neal, Carson City Councilman Mike Gipson and Compton school board member Micah Ali — know anything about the inconsistencies, they haven't said so.

Walker said he appreciated The Times' clarification of what appeared in the public record, writing in one email: "It has never been my intent to hide anything or make light of it."

What isn't disputed is that Walker's life started to change when he was still locked up at Sylmar Juvenile Hall and met Scott Budnick, a volunteer teacher for a group called Inside Out Writers.

Budnick, the producer of the "Hangover" movies, remembers Walker as smart and articulate, not given to the profanity or raw street rap of other prisoners. But he also appeared bogged down by his past failures. So Budnick told him bluntly: "Why don't you stop crying and do something about it?"

When he got shipped to the adult prison system, the skinny, 6-foot-2 teenager took that lesson with him. He decided he would defy the prevailing code of violence and strict racial alliances. When other inmates at Ironwood State Prison near the Arizona border went outside for morning recreation, Walker would stay inside and study.

Elizabeth Castillo, 17, left, a student at Compton YouthBuild, reacts after giving Prophet Walker a polo shirt as a gift from the school. Walker, 26, focuses much of his time on people who might be left behind. At the Anti-Recidivism Coalition, where onetime felons can stop by to talk and take classes, he teaches a public speaking course. At Watts United Weekends, he works with inner-city middle-schoolers at Canyon Creek Camp in the mountains near Lake Hughes.

He read books that his godfather, Richard Jones, sent to him — everything from Socrates to "The Kite Runner." Jones insisted that Walker send him back essays on what he had learned. In the afternoons, in prison vernacular, he would "yard."

"It's 120 degrees. There is no shade, period. And Prophet is out there playing basketball on the blacktop, sometimes by himself," recalled Julio Acosta, a lifer who taught Walker algebra. "It was a strategic move that worked. He minimized his exposure to the shot-callers and … dingbats and idiots."

Seeking a more hospitable home for his studies, Walker called his old mentor Budnick. He laid out a proposal for the Department of Corrections to reclassify young convicts who showed promise and allow them to transfer to lower-security prisons.

The bureaucrats went for it, adopting a pilot program that promptly sent Walker and a few others to a new college students' dorm at the California Rehabilitation Center in Norco. Over six years, the program has led to the reclassification of as many as 300 inmates, allowing their transfer to more hospitable lockups.

Said Ken Drysol, a former associate warden with the corrections department: "I think we potentially stopped the downward cycle for a lot of people."

Four years after he was released from prison, Walker participated in the graduation ceremony at Loyola Marymount University's bluff-top campus. Back at Ironwood, math tutor Acosta said he could have cried. But, he said, "I'm in prison. I'm around a bunch of dudes, so I held it together."

Only recently, after The Times called to confirm his graduation, would it be revealed that Walker was missing a one-unit lab in chemistry. He says he had assumed his diploma was just delayed but now plans to finish the class before summer to fulfill his final graduation requirement.

Even before the end of school, Walker had started working. When he joined the Westside firm Morley Builders, he helped oversee construction at the boutique Ace Hotel downtown and the "Despicable Me" attraction at Universal Studios. More recently, he left the company to join the massive development at the Jordan Downs housing project.

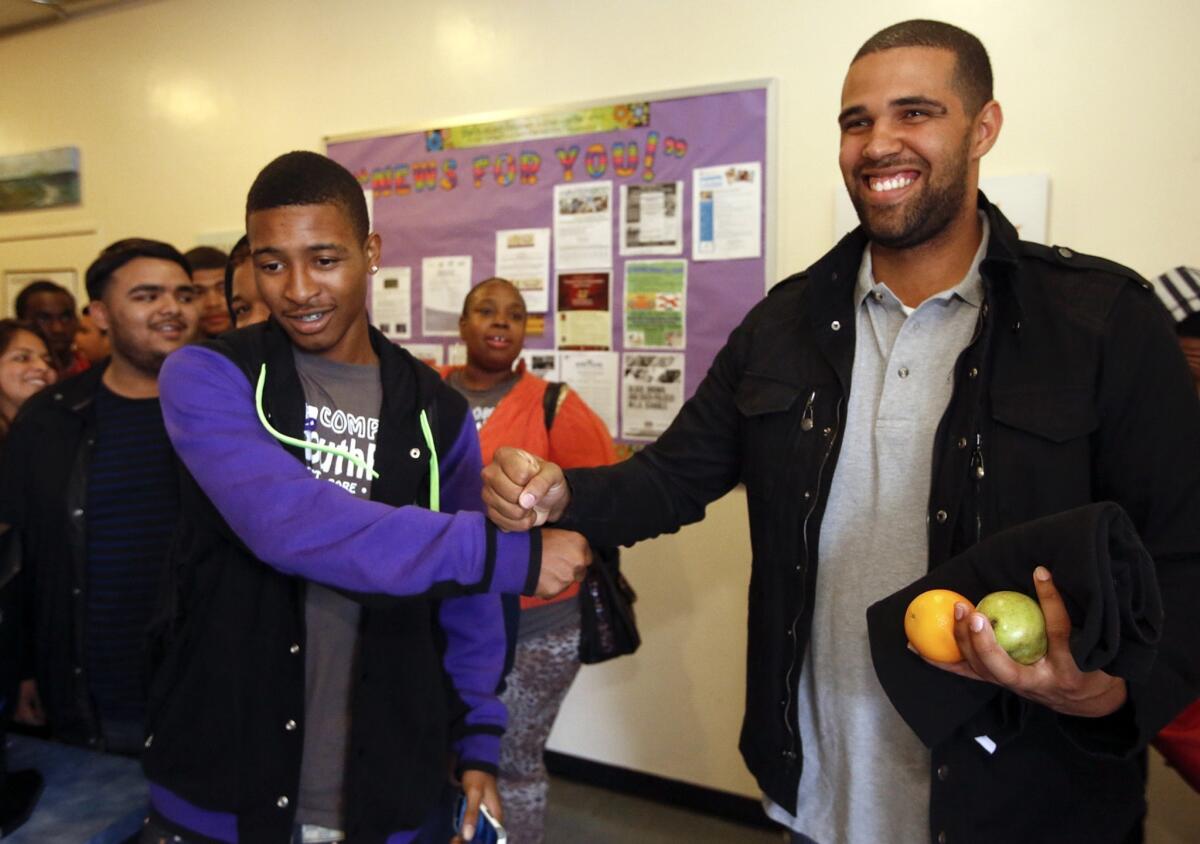

Prophet Walker, right, greets Deandre Harper, 17, after speaking to students at Compton YouthBuild. "The most heartbreaking thing to me is to see children in this area who have been stripped of their right simply to dream," Walker said.

Single and living with another ex-con (and Loyola student) in an apartment in Carson, Walker focuses much of his time on people who might be left behind. At the Anti-Recidivism Coalition — with offices in a hip, loft-like space in downtown Los Angeles — onetime felons can stop by to talk, take a meditation class or plot future prison reforms. Founding member Walker teaches a class on public speaking.

He also helped create what are now known as the Watts United Weekends. Using the Canyon Creek Camp in the mountains near Lake Hughes, the program brings together inner-city middle-schoolers to bond over games, a rope course and serious talk, away from the stress and gang rivalries of their home neighborhoods.

On a recent weekend, Walker scrambled around a lawn with a pack of teenagers, a raggedy stuffed toy at the center of a modified game of keep-away. He helped pull girls over a 12-foot challenge wall. He told sixth-grade boys in a writing group to think about building their lives, not acting tough.

"The most heartbreaking thing to me is to see children in this area who have been stripped of their right simply to dream," Walker said. "I want to give that back to them."

Follow James Rainey (@LATimesrainey) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

At the new Coachella, partyers take to the sky

Doc Rivers has been a shot in the arm for the Clippers

Let's get our heart broken or let's fall in love, one of the two.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.