Out of prison and into the unknown

George Souliotes spent nearly 17 years behind bars before his triple murder conviction was overturned. Now he’s trying to adjust to life on the outside.

For the first several days of his freedom, George Souliotes kept forgetting to zip up his trousers. Prison jumpsuits don't have zippers.

The 72-year-old left lights on at night, unaccustomed to having control over a light switch.

He stiffened whenever he accidentally brushed up against someone. Bumping into another prisoner could get him stabbed.

He had spent nearly 17 years behind bars for a triple murder conviction. A federal judge overturned the conviction after an innocence hearing, and now Souliotes was having to relearn life.

Most mornings, the Greek immigrant sat in the sunshine at a Glendale park. His son gave him a smartphone, and he labored doggedly over it. "I love the lady who helps me find my way," he said of the GPS feature. He also signed up for a class to learn how to use a computer.

At St. Sophia Greek Orthodox Cathedral, Souliotes mingled with other Greek immigrants, many of whom had followed his case. People wanted to know about prison, but he didn't like talking about it.

He wanted to forget the stabbings — he saw 17 in one day during a riot in the yard. He wanted to forget the spaghetti that came in a clump and had to be sliced. He wanted to forget the nights he cried into a towel so no one would hear.

"I want to quit talking about these things," he said. "The past is gone."

Freedom came to Souliotes on July 3.

Convicted of setting a fire that killed three of his tenants, Souliotes entered prison a middle-aged man, his wavy brown hair starting to recede. When he left, his hair was gray and mostly gone, his posture stooped and his gait marked by a limp from a bad hip. He was divorced, and his children were grown.

An innocence project accepted his case 10 years ago, and private lawyers from big-name firms worked pro bono to overturn his conviction. The forensic evidence used to convict him was reexamined, and much was discredited.

No matter what, I have to explain that I was a prisoner. ... They look at you with that fear."— George Souliotes

Michelle Jones, 30, and her two children, Daniel Jr., 6, and Amanda, 3, tenants in Souliotes' Modesto rental home, died when the house erupted in flames as they slept. Daniel Jones Sr., the husband and father, was not home at the time. Souliotes had been days away from serving the Joneses with an eviction notice and garnishing their wages for unpaid rent.

Prosecutors, seeking the death penalty, had argued that Souliotes burned the house for insurance money and maintained that a petroleum substance on his shoes matched a compound that ignited the fire. "The shoes tell the tale," the trial prosecutor told jurors. Souliotes was sentenced to life without parole. Years later a scientist proved there was no match.

The federal judge who decided Souliotes had shown "actual innocence" overturned his conviction on the grounds his trial lawyer had failed him.

After the ruling, prosecutors wanted to retry him for murder, but the state conceded during the appeal that it could not prove the fire was deliberately set, and a second conviction appeared unlikely.

In return for his immediate release, Souliotes pleaded no contest to three counts of involuntary manslaughter for failing to maintain working smoke detectors. The house had a smoke alarm, but the victims died of smoke inhalation.

The legal odyssey was over, but Souliotes' journey back to life was just beginning.

Souliotes is overcome with emotion as his son Aleko Souliotes, 38, greets him after his release from the Stanislaus Public Safety Center on July 3. At right is attorney Jimmy McBirney. (Debbie Noda / Modesto Bee) More photos

Television cameras captured the moment when he left prison.

He walked into a jail lobby in Modesto, where he had been transferred for a final court hearing, smiled and wiped his forehead in mock relief.

He wept as he embraced his two sons, his sister and his lawyers. A television reporter asked what the day meant for him.

He pointed to a glass door. "I see the sun," he said. "It is beautiful."

What are your plans? a reporter asked. "I wish I know," he said.

After that public moment, he climbed into his sister's car and the family started for her home in Glendale. Switching from Greek to English and back again, Aleka Pantazis, 66, reassured her brother that accepting the plea had been wise. His health was deteriorating, and it was time to move on.

Souliotes marveled at how much had changed. "Talking cars!" he exclaimed at the navigation system.

Aleko Souliotes, 38, his elder son, talked to him about the tasks ahead: obtain a state identification card, apply for Social Security and Medicare, take the written examination for a driver's license, buy a car and find his green card.

Pantazis counseled patience. You cannot expect to recover overnight what you have lost in 17 years, she told him.

His sons wanted to stop and treat him to a steak dinner, but Souliotes, who was born in Athens and came to America when he was 26, craved a Greek salad. He had tasted tomatoes only three or four times in prison, where an onion also was considered a prize and feta had been only a dream.

After a Greek meal in the backyard of his sister's home, Souliotes went to bed and slept soundly. He awoke at dawn and turned the knob on the bedroom door.

It opened. He hesitated for an instant. No lock, no bars, no guard. And then he went outside to watch the sun rise.

Souliotes sits in the rose garden of a house that he is helping to remodel in Escondido. More photos

In prison, he had worried that he might lose touch with reality.

"When you are in the prison, you don't have no gentle people," he said. "They are not like normal people. They are like animals."

He had made two friends inside, and he wrote their families letters from his park bench.

One, a former drug addict, received Kosher meals and sometimes shared his vegetables with Souliotes. The other, a lawyer, had been convicted of kidnapping his daughter from his estranged wife. Some of the guards had also shown him kindness.

Souliotes' happiest times after his release were with his grown children. In prison he had longed to know more of their lives.

"Poor Aleko, he tries to help me. It is so touching," Souliotes said of his son. "I am so happy just to sit down with him and talk about his dreams, what he wants to do, his plans. My days were more conservative. He is more of a go-getter, and I hope he succeeds. He is a hard worker too — reminds me of myself."

Souliotes attended a Greek wedding last month and yearned to dance. He had been a regular on the ballroom dancing circuit before his arrest and once took first place for West Coast Swing.

"I was afraid I cannot do it," he said, "not only because I am old, but because there are a lot of things I forgot."

He tentatively stepped onto the dance floor with a partner and let the music guide his feet.

"I can do it," he said, beaming. "I love it."

Souliotes wrestled at times with anger over his conviction. "What good is getting out of prison without your innocence?" he asked. He said he had hoped the state would acknowledge he had been wrongfully convicted and compensate him for his confinement, but the plea ended any such possibility.

"How many lies, how many lies," he said bitterly, recalling his two trials. "They have destroyed my life completely."

Souliotes programs his cellphone for directions to a restaurant in Escondido. He said of the female voice commands from his phone, "I love the lady who helps me find my way." More photos

Just as his case illuminated the possibility of wrongful convictions, his life after prison was revealing the hurdles inmates face once they return to society.

He had spent his life's savings on his trial defense, and he was penniless. He stood in long lines day after day in government offices to reestablish his identity and obtain benefits.

"No matter what, I have to explain that I was a prisoner," he said. "At the beginning they look at you with that fear."

He obtained Social Security, but stopped taking medication for diabetes and high blood pressure after being told that Medicare coverage would not start for several months. He asked his local congressman for help and received a letter last week saying he was fully covered.

He needs a hip replacement and new hearing aids and glasses. He was left with blurred vision in one eye after cataract surgery in prison.

Formerly a licensed general contractor, Souliotes said he hoped to earn money doing small construction jobs. He worried, though, that his body might be too weak for physical labor.

"I used to have something in my life," he said. "Today, I am begging. I never was a beggar."

He also must cope with fear. His brother-in-law has provided him with an inexpensive apartment in Los Angeles, but Souliotes wants the gas company to inspect the stove and heater before he lives there. He blames a faulty stove for the fire that killed his tenants.

Still, he said he's glad he accepted a plea deal instead of continuing a fight that might have kept him behind bars for many more months or years.

"Today just look at what I have done," he said, brightening. He mentioned a trip to the grocery store and time spent with his sons. "I have choices, and over there I had no choices."

Souliotes turns 73 this month. He said he would like one day to take his children to Greece for vacation.

"I want to live life in fullness even at my age," he said. "I think I can go back to a full life. We will see."

Follow Maura Dolan (@mauradolan) on Twitter

Follow @latgreatreads on Twitter

More great reads

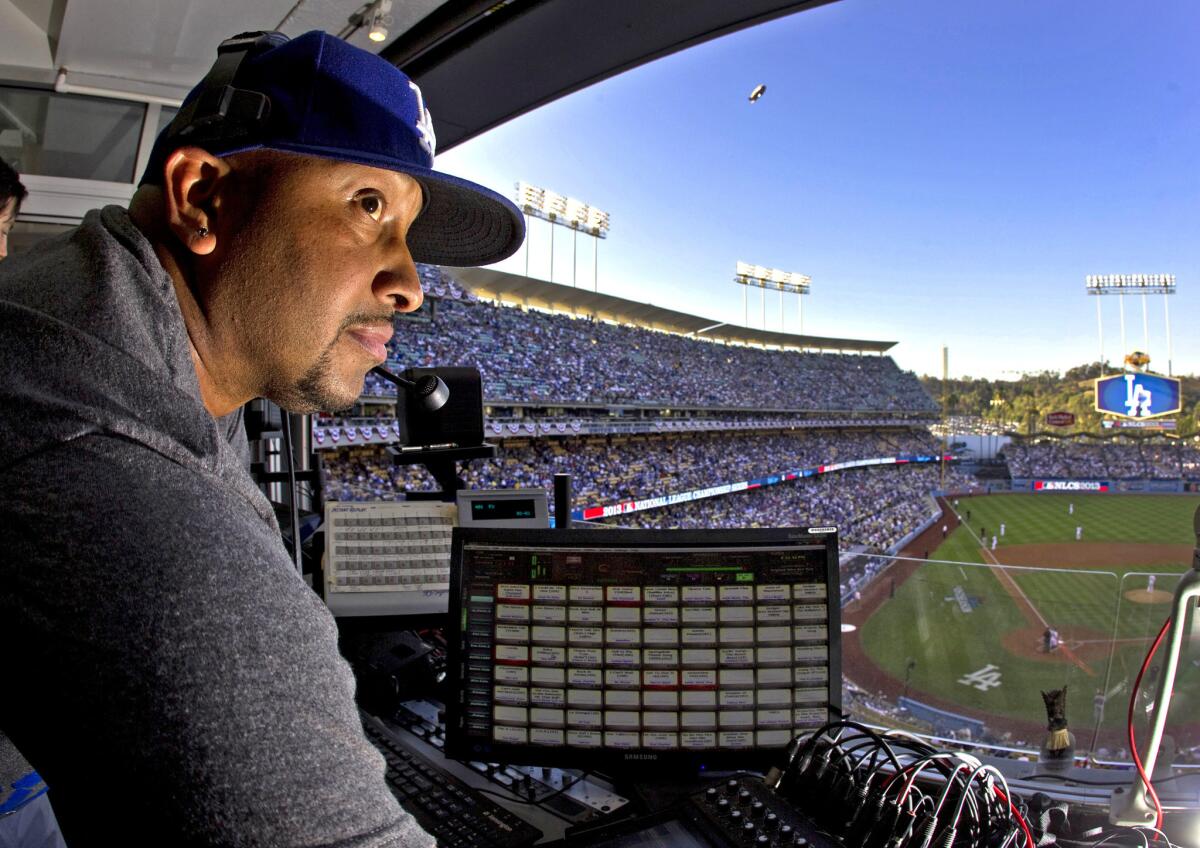

Meet the DJ who picks the songs at Dodger Stadium

When they're amped up, I try to make them go to another level."

Cockroach farms multiplying in China

People laughed at me when I started, but I always thought that cockroaches would bring me wealth."

Ousted courthouse vendor is no longer a no-ware man

I eat up the years like I eat popcorn. ... I don't feel old."

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.